Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

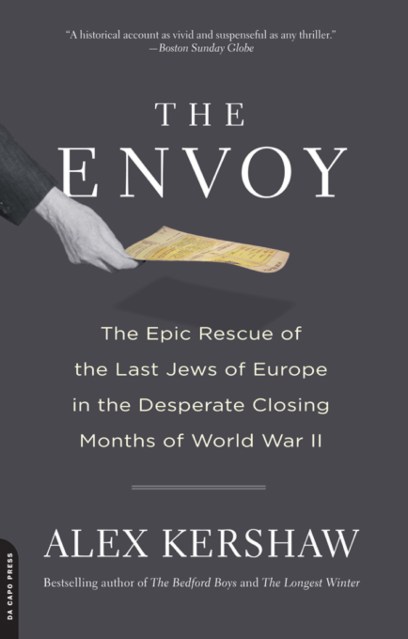

The Envoy

The Epic Rescue of the Last Jews of Europe in the Desperate Closing Months of World War II

Contributors

By Alex Kershaw

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 26, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

December 1944. Soviet and German troops fight from house to house in the shattered, corpse-strewn suburbs of Budapest. Crazed Hungarian fascists join with die-hard Nazis to slaughter Jews day and night, turning the Danube blood-red. In less than six months, thirty-eight-year-old SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann has sent over half a million Hungarians to the gas chambers in Auschwitz. Now all that prevents him from liquidating Europe's last Jewish ghetto is an unarmed Swedish diplomatic envoy named Raoul Wallenberg.

The Envoy is the stirring tale of how one man made the greatest difference in the face of untold evil. The legendary Oscar Schindler saved hundreds, but Raoul Wallenberg did what no other individual or nation managed to do: He saved more than 100,000 Jewish men, women, and children from extermination.

Written with Alex Kershaw's customary narrative verve, The Envoy is a fast-paced, nonfiction thriller that brings to life one of the darkest and yet most inspiring chapters of twentieth century history. It is an epic for the ages.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 26, 2010

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306819407

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use