By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

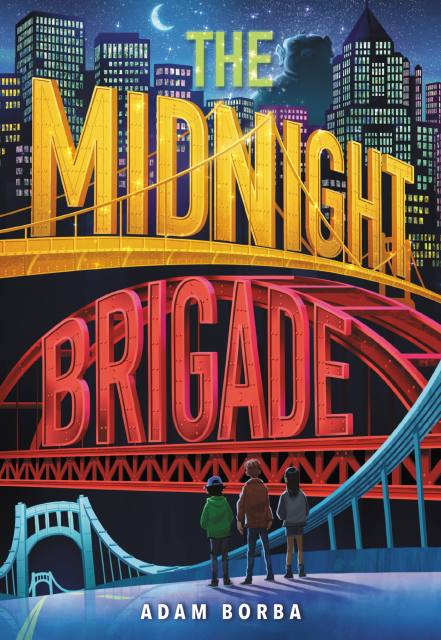

The Midnight Brigade

Contributors

By Adam Borba

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2022

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316542586

Price

$7.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $7.99 $11.99 CAD

- ebook $6.99 $8.99 CAD

- Hardcover $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Carl Chesterfield wishes he could speak up—whether that means being honest with his father about the family’s new (and failing) food truck, reaching out to a potential friend, or alerting others to the fact that monsters might be secretly overrunning his hometown of Pittsburgh. There’s plenty to fret over. And plenty to question.

When a flyer about a mysterious monster-seeking group called the Midnight Brigade catches his eye, Carl sees an opportunity to find answers. Little does he know, his curiosity will lead him to find an incredible discovery under one of his city’s magnificent bridges and to be bolder than he ever imagined. Chock-full of humor and heart, this is the quirky tale of three unexpected friends and the crankiest troll with a heart of gold.

-

* "Tongue-in-cheek frolic."Booklist, starred

-

"[The] humorous novel features a likable cast of middle school kids and their families...spot art greatly enhances the text, bringing the setting and characters' emotions to life...An unusual story about forging new bonds."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Carl’s parents are realistically flawed, and his mix of feelings around their constant fighting ring true...through Borba’s whimsical, sincere debut."Publishers Weekly

-

“Pittsburgh! Monsters! Pierogies! This book has all my favorite things packed into a delightful, mysterious adventure!”Jonathan Auxier, NYT bestselling author of The Night Gardener

-

"A delightful, deeply felt, entirely original debut. You'll remember these characters and their stories long after you close the book, and you'll never look at a bridge the same way again. I'll be sending in my application to join the Midnight Brigade right away!"Jarrett Lerner, creator of the Enginerds series

-

"...dramatic and amusing...[a] cheering read for children ages 8-12. In Mr. Borba's milieu, children admire and respect their parents, parents admire and respect their children, and trolls give good advice."WSJ

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use