By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

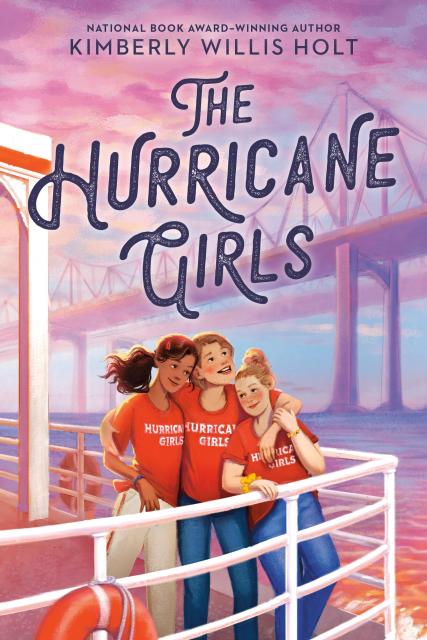

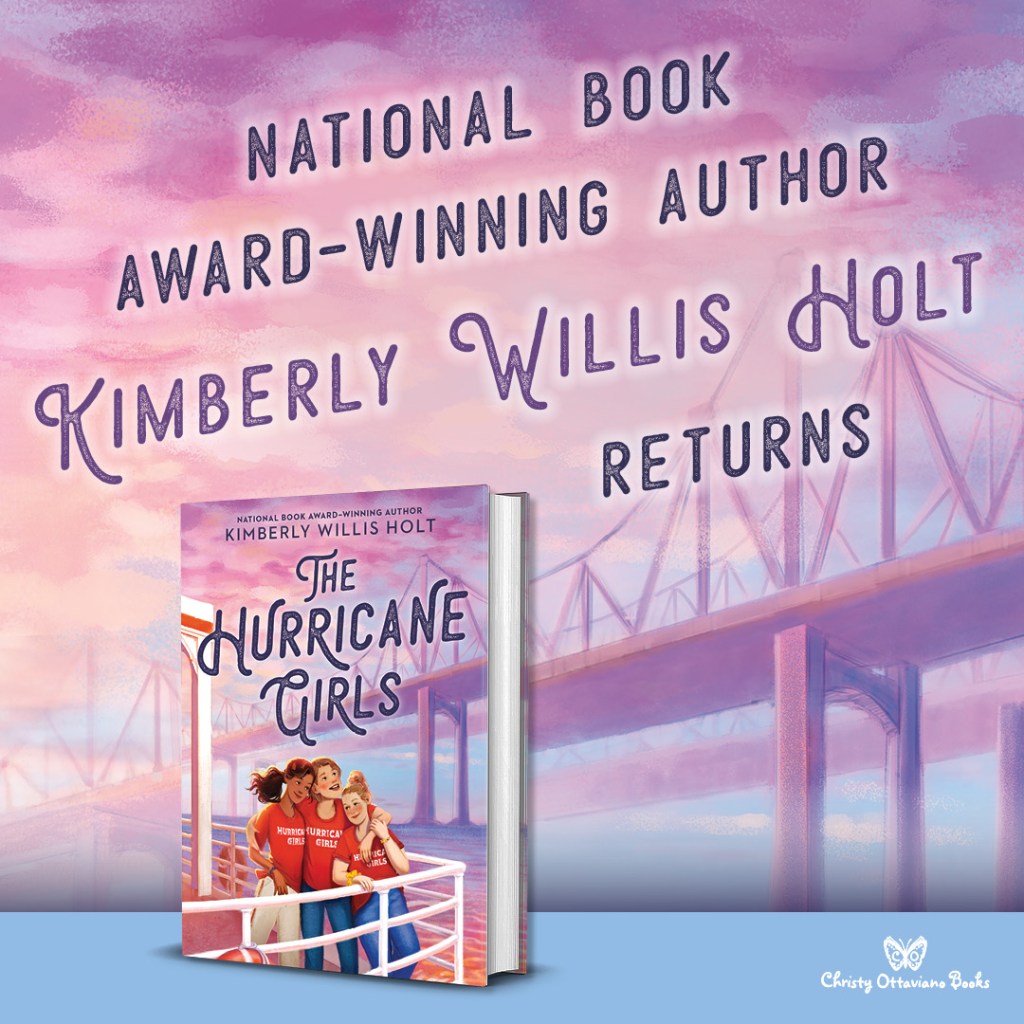

The Hurricane Girls

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 29, 2023

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Christy Ottaviano Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316326094

Price

$17.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $17.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

- Trade Paperback $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 29, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A coming-of-age middle grade novel about three best friends born in the wake of Hurricane Katrina who must confront storms of their own 12 years later, from a National Book Award-winning author.

★ “Holt takes time developing these characters, allowing readers to see both their individual and collective growth in this appealing and sensitive novel.”—The Horn Book, starred review

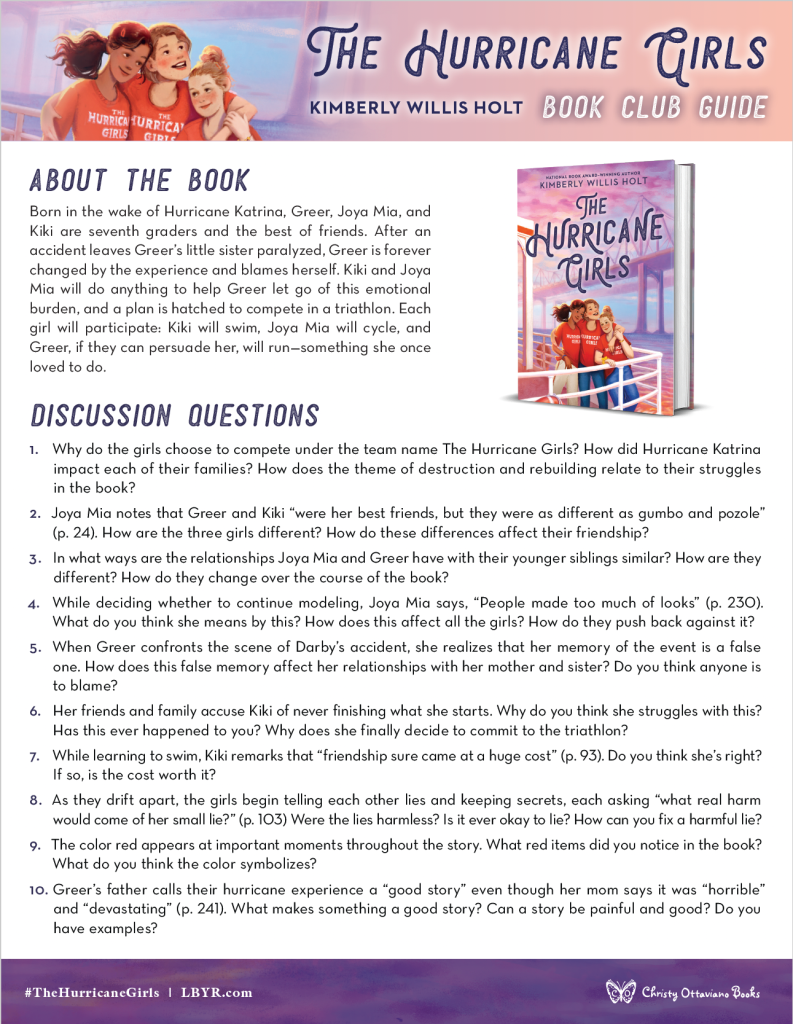

Born in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Greer, Joya Mia, and Kiki are seventh graders and the best of friends. After an accident leaves Greer’s little sister paralyzed, Greer is forever changed by the experience and blames herself. Kiki and Joya Mia will do anything to help Greer let go of this emotional burden, and a plan is hatched to compete in a triathlon. Each girl will participate: Kiki will swim, Joya Mia will cycle, and Greer, if they can persuade her, will run—something she once loved to do.

Set on the Westbank of New Orleans, this contemporary coming-of-age novel is a journey of growth, healing, and difficult transitions as the girls navigate their many life challenges: family trauma, body insecurity, and the conflict between ambition and responsibility. It’s a powerful and enlightening exploration of how to surmount personal tragedy through friendship and forgiveness.

“A tender and triumphant story about friendship and family, in a proud and resilient city.”―Deborah Wiles, author of the National Book Award finalists Each Little Bird That Sings and Revolution

★ “Holt takes time developing these characters, allowing readers to see both their individual and collective growth in this appealing and sensitive novel.”—The Horn Book, starred review

Born in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Greer, Joya Mia, and Kiki are seventh graders and the best of friends. After an accident leaves Greer’s little sister paralyzed, Greer is forever changed by the experience and blames herself. Kiki and Joya Mia will do anything to help Greer let go of this emotional burden, and a plan is hatched to compete in a triathlon. Each girl will participate: Kiki will swim, Joya Mia will cycle, and Greer, if they can persuade her, will run—something she once loved to do.

Set on the Westbank of New Orleans, this contemporary coming-of-age novel is a journey of growth, healing, and difficult transitions as the girls navigate their many life challenges: family trauma, body insecurity, and the conflict between ambition and responsibility. It’s a powerful and enlightening exploration of how to surmount personal tragedy through friendship and forgiveness.

“A tender and triumphant story about friendship and family, in a proud and resilient city.”―Deborah Wiles, author of the National Book Award finalists Each Little Bird That Sings and Revolution

-

Praise for The Hurricane Girls:The Horn Book, starred review

* "The girls’ slowly deepening understanding of themselves gives this book its heart. Like their rebuilt city, this friendship cannot reconstitute as an exact replica of what they had before…. Holt takes time developing these characters, allowing readers to see both their individual and collective growth in this appealing and sensitive novel." -

"Interpersonal conflicts threaten the friendship of three New Orleans seventh graders in this slice-of-life novel by Holt (The Ambassador of Nowhere Texas).... Nuanced relationship dynamics paired with complex characterizations drive this grounded look at the ways in which the aftermath of tragedy can reverberate long after the event and how community and connection can pave a path toward healing."Publishers Weekly

-

"Holt’s involving third-person narrative shifts focus, chapter by chapter, from one girl to the next and portrays their family relationships as well as the intricately interwoven thoughts, emotions, and memories that bind them together. While some readers may be drawn to one girl in particular, most will find themselves rooting for all three main characters in this engaging novel."Booklist

-

"A tender and triumphant story about friendship and family, in a proud and resilient city."Deborah Wiles, author of the National Book Award finalists Each Little Bird That Sings and Revolution

-

"Another outstanding novel by one of my favorite authors. Set after Hurricane Katrina, our three girls are all dealing with issues that every girl can relate to—it's Holt's superpower to bring a contemporary novel to our young readers."Valerie Koehler, owner of Blue Willow Bookshop, Houston, TX

-

"This is a wonderful story of friendship and strength."Judith Lafitte, co-owner of Octavia Books, New Orleans, LA

-

Praise for Kimberly Willis Holt:VOYA, starred review on Dear Hank Williams

National Book Award - Winner

ALA Best Books for Young Adults

ALA Notable Children's Books

Booklist Editors' Choice

Horn Book Magazine Fanfare List

School Library Best Books of the Year

Georgia Children's Book Award (U of GA)

Illinois Rebecca Caudill YR Choice Award

New Mexico Land of Enchantment

NYPL Books for the Teen Age

Texas Bluebonnet Award

Vermont Dorothy Canfield Fisher Award

* "In this companion to the author’s memorable When Zachary Beaver Came to Town, 30 years have passed and it’s 2001. Evocatively written (“stiff as burnt bacon”), this is an altogether absorbing and affecting novel. It’s obvious that Holt loves her fully realized characters and their small-town setting, and readers can’t help but feel the same." —Booklist, starred review on The Ambassador of Nowhere Texas

* "The strength of this novel lies in the insight Tate develops as she deals with tragedy and depends on the love of family. Artfully told, this middle grade novel pleases on many levels." /B>School Library Journal, starred review on Dear Hank Williams

"This book packs more emotional power than 90% of the so-called grown-up novels taking up precious space on bookshelves around the country. Kimberly Willis Holt's When Zachary Beaver Came to Town will resonate with readers." —USA Today on When Zachary Beaver Came To Town

"Holt may not take her readers on wild flights of fantasy, but her quiet novel offers a slice of life that's hard to resist." /B>New York Times Book Review on When Zachary Beaver Came To Town

* "As in her first novel, My Louisiana Sky, Holt humanizes the outsider without sentimentality.... Holt reveals the freak in all of us, and the power of redemption." —Booklist, starred review on When Zachary Beaver Came To Town

* "In her own down-to-earth, people, smart way, Holt offers a gift.... It is a lovely—at times even giddy—date with real life." —The Horn Book, starred review on When Zachary Beaver Came To Town

* "Well-developed characters, all fantastic and flawed in their own ways, add plenty of spice." —Publishers Weekly, starred review on When Zachary Beaver Came To Town

* "With tidbits of history woven throughout and the rich cast of characters, especially an endearing protagonist, Dear Hank Williams is a novel that sings from the heart."