Frozen in Time: A History of Frozen Artifacts Through the Ages

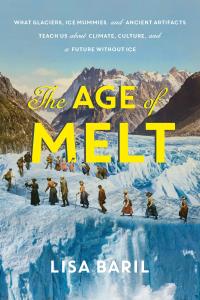

What Glaciers, Ice Mummies, and Ancient Artifacts Teach Us about Climate, Culture, and a Future without Ice

In The Age of Melt, environmental journalist Lisa Baril explores the deep-rooted cultural connection between humans and ice through time. The Age of Melt explores what these artifacts reveal about culture, wilderness, and what we gain when we rethink our relationship to the world and its most precious and ephemeral substance—ice.

A thought-provoking scientific narrative investigating ice patch archaeology and the role of glaciers in the development of human culture.

Glaciers figure prominently in both ancient and contemporary narratives around the world. They inspire art and literature. They spark both fear and awe. And they give and take life. In The Age of Melt, environmental journalist Lisa Baril explores the deep-rooted cultural connection between humans and ice through time.

Thousands of organic artifacts are emerging from patches of melting ice in mountain ranges around the world. Archaeologists are in a race against time to find them before they disappear forever. In entertaining and enlightening prose, Baril travels from the Alps to the Andes, investigating what these artifacts teach us about climate and culture. But this is not a chronicle of loss. The Age of Melt explores what these artifacts reveal about culture, wilderness, and what we gain when we rethink our relationship to the world and its most precious and ephemeral substance—ice.

1914 – The First Discovery from the Ice

An amateur archaeologist and collector hiking along the edge of an ice patch in Norway discovered a wooden arrow still fletched with bird feathers on one end. A notch on the other end of the arrow secured a bone point tied to the shaft with sinew.

A decade later and halfway around the world, another complete arrow melted from an ice patch in British Columbia. But these early discoveries were regarded as “mere curiosities and not the harbingers of a soon-to-be globally relevant research frontier.”

Once the ice began to melt in earnest some decades later, a bonanza of artifacts would start melting out of ice patches worldwide sparking an entirely new branch of archaeology focused on melting ice.

1991 – Ötzi the Iceman

A German couple vacationing in the Italian Alps were on their way down a mountain summit when they noticed something odd breaking the surface of the snow.

As they approached, one of them exclaimed, “Look, it’s a person!” The couple had unwittingly discovered one of the most fascinating mummies of all time – a 5300-year-old corpse from the late Neolithic. Ötzi, named after the mountain range in which he was found, was so well preserved by ice and snow that bits of brain clung to his skull and the undigested contents of his last meal were enveloped within his shriveled stomach.

From Ötzi’s tools, clothing, and Ötzi himself, scientists have reconstructed the Iceman’s life, from where he was born to his last hours.

1997 – Human History Melts Out of Yukon Ice Patches

Six years after Ötzi’s discovery, two hunters in the Southern Lakes region of Canada’s Yukon Territory found a patch of ice covered by a thick layer of caribou dung. A perfectly-preserved arrow shaft lay along the ice’s muddy edge.

The ice patch lies along the slope of Thandlät Ddhal, which means “sharp–pointed mountain” in Dákwanjè (Southern Tutchone)—a language spoken by the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations whose traditional lands they were hunting.

Caribou seek ice to cool off and escape biting insects. Ancient hunters used this habit to their advantage. When a hunter missed his or her shot, the arrow sliced through the ice where it remained until the ice around it melted.

Since 1997, thousands of objects spanning 9000 years of human history have melted out of Yukon’s ice patches.

1999 – Another Ice Mummy!

Another ice mummy! In an extraordinary bit of luck, three hunters discover the remains of a second ice mummy in Tatshenshini-Alsek Park–in the traditional lands of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations.

Kwäydąy Dän Ts’ÌnchÌ, which means “Long Ago Person Found” in southern Tutchone, died roughly 250 years ago at the tail end of the Little Ice Age. Like Ötzi, scientists have pieced together a remarkable account of his life and final days, during which he traveled from the coast to the interior where he met his end on a glacier.

2004 – Roman Age Artifacts

In Switzerland’s Bernese Alps, between the headwaters of the Rhone River and the valley of the rivers Simme and Kander, lies a narrow notch eroded out of hard alpine limestone. It is in this notch that 6800 years of history has melted out of a withering patch of ice.

One of the most common artifacts found in this ice patch were Roman Age hobnails, which were used to secure soles to the leather uppers of shoes, which speaks to the large number of people who used the pass to travel between valley settlements.

People still travel through the Alps via alpine passes, but rather than as a means of travel, today’s visitors are in it for the spectacular scenery of the Alps (and with much better footwear).

2007 – Lost 10,000 years ago and Found in an Ice Patch

In late summer 2007, archaeologist Craig Lee was surveying a patch of ice near Yellowstone National Park when he noticed what looked like a small branch poking through the snow.

The branch turned out to be the foreshaft of an ancient hunting weapon called an atlatl dart or throwing spear. It had been carved from a birch sapling more than 10,000 years ago. It is the oldest organic artifact ever to be recovered from an ice patch.

On closer inspection, Lee noticed three evenly spaced notches on either side of the weapon, which Lee thinks were made by the hunter to indicate ownership. In other words, the hunter expected to get his weapon back.

2010 – The Land of Frost Giants

Mimisbrunnr Klimapark in south-central Norway is unlike any other park in the world. Part museum, part art exhibit, Mimisbrunnr is a 230-foot-long tunnel carved into the Juvfonne ice patch at the edge of Jotunheimen National Park–the land of frost giants (the jötnar) of Norse mythology.

The park was founded after relics belonging to ancient reindeer hunters began melting out of the Juvfonne and other nearby ice patches. Mimisbrunnr’s exhibits, which include Viking Age arrows and unusual artifacts known as scaring sticks, are showcased in perfectly clear windows of ice, artfully lit in frosty blues and cool greens.

Scaring sticks are long wooden poles with fabric “flags” attached to one end. These strategically placed flags were meant to “scare” reindeer toward hunters waiting behind stone blinds.

201- Skiing Through the Ages

A long wooden ski complete with its leather foot binding emerged from the Digervarden ice patch in Norway.

Two years later, its mate was discovered at the same ice patch.

This pair of skis was last worn some 1300 years ago by a hunter or perhaps someone traveling through the mountains. The skis, made of birch, would have been lined with fur on the underside. Like modern day “skins,” the fur lining helped control the skier’s speed when going downhill while also providing traction on uphill climbs.

Skiers may have also used a long wooden pole to provide the skier support—a setup still used by traditional skiers in the Altai Mountains along the Mongolia-China border.

2019 – Mongolian Ice Patches

Until this year, the vast majority of ice patch artifacts were discovered in Europe and North America. But an archaeologist working in the Altai Mountains of northwestern Mongolia discovered that ancient people there also hunted at ice patches.

Archaeologist Will Tayler found dozens of arrow shafts, dart points made of wood and bone, and dozens of Argali sheep skulls along the 13,000-foot east face of Tsengel Khairkhan.

The skulls seemed to be intentionally placed. In Mongolia, the head of an animal is imbued with special significance, and the skulls of deceased horses are often placed at high mountaintop stone cairns called ovoos. The Argali sheep skulls may have been placed as part of a ritual following a successful hunt.

2024 – What Will They Find Next?

During late summer and early autumn, ice patch archaeologists head into the mountains to scout for artifacts that might have melted out of ice patches over the summer.

What will they find? A pair of skis in Mongolia? Shoes from a long ago traveler? Or perhaps another frozen mummy? After all, people have been traveling through, hunting in, and living among the mountains for millennia.

Find out what the ice reveals next:

A thought-provoking scientific narrative investigating ice patch archaeology and the role of glaciers in the development of human culture.

Glaciers figure prominently in both ancient and contemporary narratives around the world. They inspire art and literature. They spark both fear and awe. And they give and take life. In The Age of Melt, environmental journalist Lisa Baril explores the deep-rooted cultural connection between humans and ice through time.

Thousands of organic artifacts are emerging from patches of melting ice in mountain ranges around the world. Archaeologists are in a race against time to find them before they disappear forever. In entertaining and enlightening prose, Baril travels from the Alps to the Andes, investigating what these artifacts teach us about climate and culture. But this is not a chronicle of loss. The Age of Melt explores what these artifacts reveal about culture, wilderness, and what we gain when we rethink our relationship to the world and its most precious and ephemeral substance—ice.

Praise

-

Sara Dykman, author of Bicycling with Butterflies

“The Age of Melt proves everything is connected—including volcanoes, ice, and all of humanity—and that there is a good story behind every one of these connections. Reading this book deepened my love of the earth, my amazement at the ingenuity of people striving to understand, and my resolve to keep fighting against climate change. The Age of Melt is a love letter to our perfectly complicated world.”

-

Meg Lowman, National Geographic Explorer and author of The Arbornaut

“The Age of Melt offers amazing insights on ice. This book not only demystified the cryosphere, but it also explains the critical links between melting ice and the future of our warming planet. A MUST read!”

-

Lauren E. Oakes, author of In Search of the Canary Tree and Treekeepers

“Lisa Baril takes us on a riveting journey to decipher what the Earth’s melting ice reveals about the past, present, and future. In a striking blend of climate history, culture, and archeological exploration, The Age of Melt weaves together the timely discoveries that come from our vanishing ice. Writing like a detective who pieces together clues from around the world, Baril delivers a page turner.”

-

Ben Goldfarb, author of Crossings and Eager

“The Age of Melt is a collection of fast-paced, enthralling scientific detective stories set in the world’s highest, coldest, most breathtaking places. Ice patches and glaciers may look lonesome and inhospitable to modern eyes, but Lisa Baril shows that few environments reveal more about humanity’s past—nor are more inextricably tied to our future.”

-

Nature

“In The Age of Melt, science journalist Lisa Baril takes the reader on a well-crafted and entertaining journey into Earth’s frozen realms.”