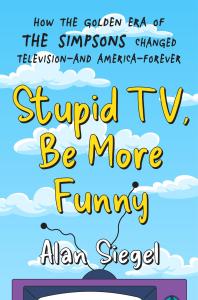

Excerpt from STUPID TV, BE MORE FUNNY by Alan Siegel

INTRODUCTION

“WHO WOULD HAVE GUESSED READING AND WRITING WOULD PAY OFF?”

— HOMER SIMPSON

This story begins in that unforgettable spring of 1990. The Cold War was finally coming to an end. America was on the verge of a crushing recession. And NASA was receiving the first mind- blowing photographs from the Hubble Space Telescope.

Alas, I knew nothing about any of that.

Back then, I was a first grader in suburban Boston. The intricacies of the world’s sociopolitical climate would have to wait. I was way too busy collecting Wade Boggs baseball cards, watching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and playing Super Mario Bros. 3 on Nintendo. I was also just starting to hear about a new animated TV series called The Simpsons. At school, it seemed like all my classmates were wearing Bart Simpson T-shirts over their billowy Z. Cavaricci pants.

The primetime cartoon had begun as interstitial shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show, a sketch comedy series that aired on Fox, which in those days was still a fledgling network. Even without really knowing what the show was about, it didn’t take long for me to succumb to peer pressure. I asked my parents if I could watch. My dad had gone to Woodstock and managed a band in the ’70s. My mom loved movies and TV and celebrity gossip. They weren’t prudes. But before giving me the green light, they wanted to see The Simpsons for themselves.

None of my friends seemed to know that the series was made for adults, not children. In the episode my mom and dad recorded on a VHS tape, Bart snaps a photo of Homer canoodling with a belly dancer at a bachelor party. Marge finds out, and then temporarily kicks him out of the house. Unluckily for me, “Homer’s Night Out” was the most risqué thing the sitcom had done to that point.

The titular character eventually learns an important lesson: it’s wrong to treat women as sex objects. My liberal folks surely appreciated the message, but they decided that the sight of a half-naked lady named Princess Kashmir was too much for their seven-year-old to bear. And so The Simpsons was thereby outlawed in the Siegel household. Left out as I felt at school, I wasn’t alone. Concerned parents across the country kept it from their kids. Naturally, the ban only made me want to watch it even more.

Looking back on it, Stuart and Debbie Siegel made a reasonable decision. Even that episode’s writer understands. “We have multiple friends who don’t let their kids start watching The Simpsons until they get older,” Jon Vitti says. “And I’m fine with that. I don’t urge it, but I totally get it. Sometimes it’s really fun with friends’ kids as they grow up and they reach the age when they’re allowed to watch The Simpsons and it’s a new show to them.”

Thankfully, I didn’t have to wait all that long. After tolerating my whining for a few weeks, my parents lifted the ban. They don’t remember having a change of heart. I think the show’s pull was too strong for them to fight. In the early 1990s, it was everywhere. Tens of millions of people were tuning in. It was a remarkable feat for a series that aired on Fox, which one TV executive called “a coat hanger network”—as in you needed to use a coat hanger as an antenna to get reception. I talked about The Simpsons incessantly with my buddies, even if series creators Matt Groening, James L. Brooks, and Sam Simon didn’t make it for us.

“It was never written for children, it was always written for grown-ups,” Yeardley Smith, the voice of Lisa Simpson, once told me. But it still felt accessible to kids, who could enjoy the show even when the adult jokes were flying over their heads. “There’s so much physical comedy, and the colors are primary colors,” Smith reminded me. “Red, blue, yellow. The animation is simple and pleasing. An eight-year-old can go, ‘Oh my God, Bart’s the funniest kid I ever saw,’ and a parent can go, ‘Holy shit, that was a joke about sex in a marriage.’ A lot of the success of The Simpsons is that it’s multigenerational.” When parents got past the subversiveness, they started watching with their kids. It brought families together.

Now ’90s kids who grew up on The Simpsons have become tastemakers and power brokers. The animated series is a true American institution. It wasn’t only a water cooler show. It altered the way we talked while crowded around the water cooler. Ever describe something mediocre as “meh”? Thank The Simpsons for helping push the word, as well as dozens more, into the lexicon.

But its current status as a beloved sitcom that’s still going after thirty-six years on the air undercuts the fact that it was revolutionary. In its decade-long heyday, the show was so radically different from everything else on TV that it hooked us. It wormed its way into our collective consciousness, influencing American culture in ways that nothing ever has. The story of the early seasons of The Simpsons and the story of this country in the ’90s are intertwined. You can’t tell one without the other.

The Simpsons helped turn Fox into the fourth major TV network while also poking fun at the institution of network TV. It sent up celebrity worship while becoming a global phenomenon. It rolled its eyes at the culture wars while finding itself in the middle of them. It ripped corporate grift while piling up billions of dollars shilling thousands of products. And it ridiculed media saturation but also inadvertently contributed to its insidiousness.

The show managed these contradictions because it was, well, so damn good. Its legendarily talented cast and writers teamed up to reinvent the sitcom and change comedy for the better. The primetime cartoon was both groundbreakingly subversive and surprisingly whole- some. Nothing in the ’90s was better at showing us where America was headed. It pointed out the cracks in the country’s facade while somehow allowing itself to be slightly optimistic about the future.

And by the late ’90s, as the optimism of the early part of the decade was curdling, the show reached uncharted territory. It reached an impossibly high comedic peak and the only way to go was down. Later seasons are often funny and worth watching, but they’re not the ones we reference all the time, sometimes even subconsciously. They’re not memed into oblivion.

Since I was a kid, I’ve been obsessed with The Simpsons. In the late ’90s, my summer camp bunkmates used to stay up late reading the first official episode guide out loud to each other, howling at all the best lines and bits we missed on first viewing. As I grew up, my fascination with the show, and particularly its golden age, never waned.

I’ve spent the last fifteen years of my professional life trying to figure out how and why, exactly, the glory days of The Simpsons were so influential to my generation. I’m admittedly not alone. Since the premiere in 1989, journalists and critics have written countless words about the series’ creation. By now, it’s no secret that the show’s three principal architects didn’t always get along. But to me, the tension among Groening, Simon, and Brooks is far less interesting than the tension between the show and American society in the ’90s. The country didn’t realize it yet, but it was ready for The Simpsons.

“I always say the basic dynamic of show business is: give people what they want,” says Simpsons writer Jeff Martin. “But if you give them something they didn’t know they wanted, then they’ll follow you anywhere.”

This is the story of how the early days of The Simpsons changed pop culture forever. It was so prescient in its prime that it basically became a coherent worldview. The way the show saw it, American life was one crushing defeat after another. And still not a lost cause. That contradiction remains one of the only ways left to make sense of a real- ity so absurd that not even The Simpsons could’ve imagined it.

Thank God my parents caved.

Excerpt from Stupid TV, Be More Funny by Alan Siegel, coming this June.

Pre-order your copy now.

“The best Simpsons book ever.”―Alan Sepinwall, Rolling Stone’s chief television critic and author of The Soprano Sessions and TV (The Book)

The Simpsons is an American institution. But its status as an occasionally sharp yet ultimately safe sitcom that’s still going after 33 years on the air undercuts its revolutionary origins. The early years of the animated series didn’t just impact Hollywood, they changed popular culture. It was a show that altered the way we talked around the watercooler, in school hallways, and on the campaign trail, by bridging generations with its comedic sensibility and prescient cultural commentary.

In Stupid TV, Be More Funny, writer Alan Siegel reveals how the first decade of the show laid the groundwork for the series’ true influence. He explores how the show’s rise from 1990 to 1998 intertwined with the supposedly ascendent post-Cold War America, turning Fox into the juggernaut we know today, simultaneously shaking its head at America’s culture wars while finding itself in the middle of them. By packing the book with anecdotes from icons like Conan O’Brien and Yeardley Smith, Siegel alaso provides readers with an unparalleled look inside the making of the show.

Through interviews with the show’s legendary staff and whip-smart analysis, Siegel charts how The Simpsons developed its singular sensibility throughout the ‘90s, one that was at once groundbreakingly subversive for a primetime cartoon and shockingly wholesome. The result is a definitive history of The Simpsons‘ most essential decade.