Excerpt from COMEDY SAMURAI by Larry Charles

PROLOGUE

IS THIS THE END?

March 27, 2024

It seemed like just another typical Friday night at the Charles house. Dinner from DoorDash in front of the TV watching a movie or show with my wife, Keely, and our son, McLain, twenty, while our two big black Malinois, Rama and Kali, whimpered and barked and humped each other to guarantee distraction. Since the pandemic, Keely and I had pretty much stopped going out. We were not social animals to begin with so we sort of loved the excuse to stay home. And that continued once the pandemic ended. Did it end?

I had been diagnosed as an adult-onset type 1 diabetic back when I was about forty, and though it is a life-changing diagnosis, one I had struggled with especially in those first few years, now at sixty-seven I had finally figured out how to deal with it, as imperfect as that process must inevitably be. Calculating carbohydrates, and units of insulin. Many thousands of pinpricks to monitor blood sugar and the needles. It takes its toll. Sometimes more mentally and emotionally than physically. At first. Weirdly, in many ways, I was healthier as a result of my diagnosis. It forced me to be serious about exercise and diet and, as best I could, my mental state. But based on my regular visits to my endocrinologist, I was in great health. All the possible ramifications and consequences of diabetes hadn’t hit me. My heart and brain and circulation and eyesight were all great and had hardly changed in twenty-seven years.

I didn’t like to share my diagnosis with my professional colleagues and kept it hidden from most. Of course, every time I direct a movie, I must have a physical for insurance purposes and have never been denied. So those doctors, and I guess, the producers who had access to those reports knew. And I would usually tell my assistant director, the AD, the right-hand person to a director on set, so that if by chance, anything would happen to me, they’d have that vital piece of information.

I don’t believe I ever told Sacha through our three movies together. Or Paul and Helen on Mad About You. Or the Entourage guys. Or Billy Crystal. Or Nic Cage. I don’t remember ever mentioning it to Bill Maher once until recently. What for? I didn’t want them to judge me or have a lack of faith or confidence in my ability.

I did mention it to Larry David, who was a close friend and mentor, on more than one occasion, but every time I brought it up, he would say, shocked and surprised as if it were the first time I’d mentioned it, “You’re diabetic?!”—until I simply stopped saying it.

Of course, he and Bill were always quick to share their health problems with me, and I was always discreet with that information, not sharing it with anyone. Old Jews talk about their health. But I didn’t.

As I reached my sixties, it seemed like I might be the lucky one who escapes or sidesteps the consequences of this condition. I felt great. And so I began to get lazy.

My A1C crept up. My blood pressure crept up. My weight crept up. I was on many annoying medications. But like the insulin injections, I had gotten used to them and thought that, as long as I stay on that routine, I should be okay.

I had stopped smoking cigarettes for good a decade before, after many years of stopping and starting. But I was still smoking pot. Sometimes a lot. Like that night.

And Keely and I and McLain were having a great time on that Friday night. My recent obsession had become obscure Eastern Euro- pean vodka. I was so proud, I had taken to collecting the unique bottles. And they were adding up. I enjoyed pretending that I was a Russian peasant knocking back straight shots while I ate food from the old country (smoked fish, pickles, etc.). Not every day. Not even necessarily every week. But that week I had done it twice in a row. The vodka that night was Stumbras, an organic vodka from Lithuania.

And I felt fine when later I climbed the stairs to our bedroom and flopped into bed. Then it hit me. Not pain. But a pressure I had never experienced before. It wasn’t just my chest. It was my entire upper torso. And my head! I knew I was in trouble. Keely knew something was wrong as well. She asked if she needed to call 911. I hated the idea of calling 911. I said no at first, thinking it was going to pass. Thinking I could will it to go away. But it didn’t. My Apple Watch told us that I was in A-fib. My heart rate was in radical fluctuation from high to low. I finally acquiesced. “Call 911.”

We live at the top of a canyon, and there is no shortcut to get here so it took a few minutes for the ambulance to arrive. I worried about things like the neighbors knowing something was wrong. We had been so private. Now I would be carried out on a stretcher for all to see. I was embarrassed.

But there was no greater sense of relief than when the EMTs came rushing up to my bedroom. They were like a football team or an army platoon. I knew they’d take care of me. And I didn’t care who knew what.

They carried me down the stairs. One of the paramedics saw the posters on my walls. A Masked and Anonymous poster from Japan. An original Religulous poster. And a large poster of Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend given to me as a gift from my eldest daughter, Sophie. As they lowered me down the staircase, he asked if I was a Godard fan. I said yes! And Weekend might be my all-time favorite movie. He concurred. We traded laudatory references to some of Godard’s other celebrated work, such as Contempt and Alphaville, and I thought, A paramedic who’s into Godard. How cool!

With Keely sitting up front with the driver, suffering vicariously with me, I retched into a plastic bag as the ambulance careened down our canyon road, past damaged or destroyed or nonexistent guardrails over which cars that had not successfully negotiated the windy hairpin turns went off the side.

One of the paramedics was named Steelhammer. That was the name on his name plate. It sounded like an action hero from the ’70s or at least a parody of an action hero from the ’70s. In between retching, I asked him if that was real and he said, as he must’ve a thousand times before, “Yup, that’s my name,” while he monitored my plummeting blood pressure.

We finally made it to the Pacific Coast Highway.

The juxtaposition of being in a racing ambulance on PCH was not lost on me either. I had never sat backward on this road so I saw it from a brand-new perspective. It was beautiful. Would it be the last time I would see it? I had lost control of my narrative.

How did I get here? I had wandered through the comedy desert. I had come to the promised land, but like a comedy Moses, I could not enter. I had come to the banks of the River of Comedy that separated the Almosts from the Alreadys, but like the restless outsider I was and would always be, I knew I would never wade in, never cross it. I had encountered the inadvertent oracles who generously shared their wisdom and prophecy with me and changed and shaped me and also warned me, warnings I had often ignored, without them even knowing it. I did what I could do and didn’t what I couldn’t. I had destroyed the golden calves, the false idols, but could not change my fate.

I took a violent approach to comedy. A seriousness. An intensity. I treated comedy like life and death. Honor and dishonor. Pride and shame. Triumph or humiliating failure. This wasn’t a pretense. I didn’t know how to be pretentious. I came from the streets of Brooklyn and everything was on the line. Laughter had to hurt. Laughter had to kill. It had to mean something. It had to mean that much. It had to be as important and impactful as crying. As dying. Comedy had to be as serious as drama. I came from the working classes. I didn’t come from the ruling classes. The elite. The privileged. The aristocracy. I was given nothing, handed nothing. If I wanted it I would have to take it. And when others needed help, I would be there. Without hesitation. A Comedy Samurai. I was a soldier and I had a job to do. And when that job was done, I moved on. Every project was a village in need of saving. And I was there to do nothing less than to save it. To rescue it from death. By killing. With laughter. It was the comedy version of the Bushido Code.

It seemed like only yesterday that I was a clueless kid from Brooklyn who’d come out to LA to find fame and fortune and had succeeded but not in any way I could’ve imagined. It was the beginning of this life, and now, alas, this could be the end.

Excerpt from COMEDY SAMURAI by Larry Charles, coming this June!

Pre-order your copy now.

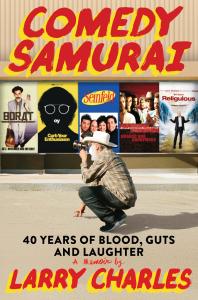

To tell Larry Charles's life story is to tell the story of modern American comedy. Over the last 40 years, few comedians have been a part of so many iconic, beloved projects. Larry was one of the original writers and producers on the first five seasons of Seinfeld, executive produced both Curb Your Enthusiasm and Entourage while directing 18 episodes of Curb, and served as the showrunner for Mad About You. His film directing credits include Borat, Bruno, and The Dictator, the comic documentory Religulous starring Bill Maher, and Masked andAnonymous, which he co-wrote with Bob Dylan who stars.

In Comedy Samurai, Charles pulls back the curtain on the making of his successful projects, offering sharp, never-before-told anecdotes about Jerry Seinfeld, Sacha Baron Cohen, Bill Maher, Bob Dylan, Nic Cage, Mel Brooks, Julia Louis-Dreyfuss, and Larry David, among many others.

Perfect for fans of Seinfeldia and lovers of comedy in general, Larry promises to offer new insights about many of the most beloved shows, films, and actors of all time.