By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

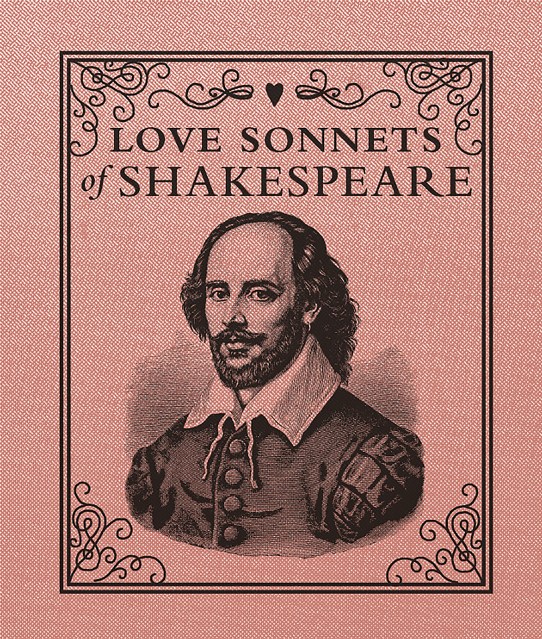

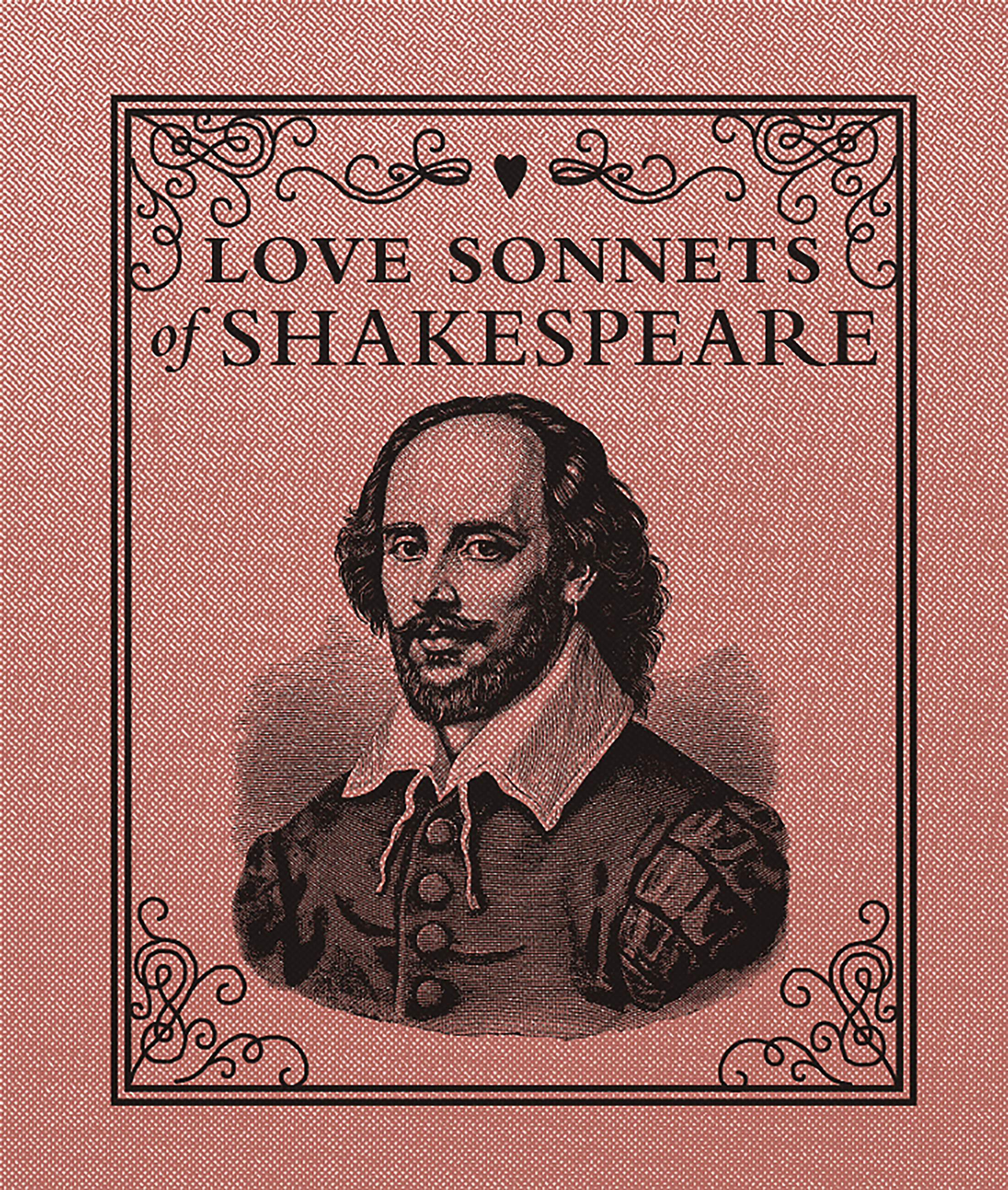

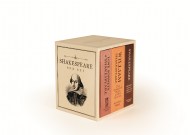

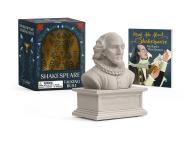

Love Sonnets of Shakespeare

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 29, 2014

- Page Count

- 176 pages

- Publisher

- RP Minis

- ISBN-13

- 9780762454587

Price

$7.95Price

$10.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $7.95 $10.50 CAD

- ebook $5.99 $7.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 29, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Once it blooms, it changes everything. Love is uplifting, enlightening, transforming. In this timeless collection of more than 80 sonnets, William Shakespeare pays tribute to our most beautiful emotion. Read and share them with the one you love.

RP Mini books measure approximately 2.5 inches by 3 inches tall, carefully bound for a great reading experience, and illustrated throughout.

Genre:

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use