By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

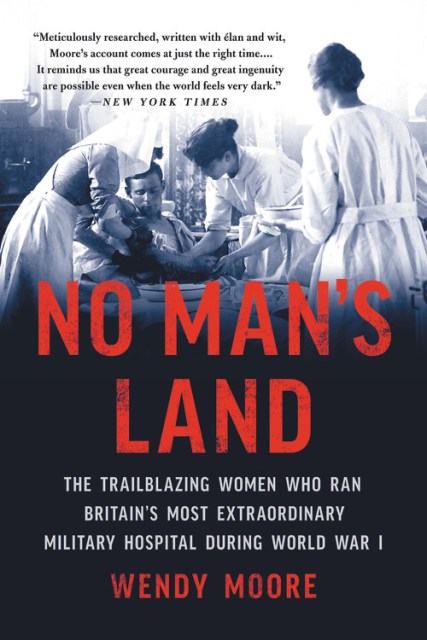

No Man’s Land

The Trailblazing Women Who Ran Britain's Most Extraordinary Military Hospital During World War I

Contributors

By Wendy Moore

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 13, 2021

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541672758

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 13, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The “absorbing and powerful” (Wall Street Journal) story of two pioneering suffragette doctors who shattered social expectations and transformed modern medicine during World War I.

A month after war broke out in 1914, doctors Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson set out for Paris, where they opened a hospital in a luxury hotel and treated hundreds of casualties plucked from France’s battlefields. Although prior to the First World War, female doctors were restricted to treating women and children, Murray and Anderson’s work was so successful that the British Army asked them to run a hospital in the heart of London. Nicknamed the Suffragettes’ Hospital and staffed from top to bottom by women, Endell Street soon became known for its lifesaving treatments and lively atmosphere.

In No Man’s Land, Wendy Moore illuminates this turbulent moment of global war when women were, for the first time, allowed to operate on men. Their fortitude and brilliance serve as powerful reminders of what women can achieve against all odds.

In No Man’s Land, Wendy Moore illuminates this turbulent moment of global war when women were, for the first time, allowed to operate on men. Their fortitude and brilliance serve as powerful reminders of what women can achieve against all odds.

Genre:

-

"Meticulously researched, written with élan and wit, Moore's account comes at just the right time... No Man's Land reminds us that people can rise to an occasion, that the biggest advances -- for medicine, for humanity -- can come during the toughest times, as a result of the toughest times. It reminds us that great courage and great ingenuity are possible even when the world feels very dark."New York Times

-

"An absorbing and powerful narrative of how two determined women used the crisis of war to create an opportunity to accomplish goals that they couldn't achieve in peacetime....Ms. Moore has an eye for detail that brings her story to life."Wall Street Journal

-

"Fascinating, carefully researched... Wendy Moore vividly depicts the convoys of seriously wounded soldiers arriving straight from the battlefields in France in the hospital's courtyard in the middle of the night... Moore is superb at describing the medical advances that resulted in seven research papers by Endell Street doctors being published in The Lancet, among the first ever by women."The Guardian

-

"Fascinating"Times (UK)

-

"Rarely is a book so important, so timely. Medical journalist and author Moore has written a masterpiece... an unmissable, thrilling read."London Evening Standard

-

"Drawing on rich archival material, Moore crafts a compelling history of the challenges faced by women doctors in the early years of the last century... An absorbing history of courage."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Crisp, novelistic... Moore narrates with verve and precision."Publishers Weekly

-

"No Man's Land is a story of feminist aspirations, bureaucratic hurdles overcome, medical innovation, and unexpected freedoms created in the turbulence of war. It is an important and well written addition to the growing body of forgotten women's history."Shelf Awareness

-

"If you're fascinated by today's miracle medicine, this one's for you. This true tale details two pioneering doctors who transformed modern medicine while breaking societal norms during World War I."Seattle Post-Intelligencer

-

"Wendy Moore's skill as a writer delivers the story of these women and the history of the war with exceptional power, laying out a compelling combination of casualty statistics and individual human stories."New York Journal of Books

-

"This well researched, well written story makes a strong case for how British suffering during the Great War would have been even worse if not for the heroic female physicians who previously were allowed to operate only on women and children."Booklist

-

"Moore eloquently brings to life the story of the two women who fought for women's rights and set up Endell Street Hospital-nicknamed the Suffragettes' Hospital and staffed entirely by women."Scientific American

-

"How can a spectacular story like No Man's Land just disappear? Luckily for us, it fell into the hands of one of our finest biographers. Wendy Moore's rich storyteller's voice has brought back the lives and achievements of these brave and brilliant women."Andrea Wulf, author of The Invention of Nature

-

"No Man's Land is an absolute delight. Wendy Moore has performed an incredible feat of historical detective work, and the result is a gripping account of courage and determination in the face of death. It is impossible not to love the 'suffragette surgeons' as they fought for the wounded abroad and for women's rights at home."Amanda Foreman, author of The Duchess

-

"Few authors write as colorfully and compellingly about the past as Wendy Moore. In her deft hands, the horrors of the First World War and the heroic efforts of the suffragette surgeons are conjured back to life. Meticulously researched and beautifully executed, No Man's Land is an important book that shows Moore to be the masterful storyteller that she is."Lindsey Fitzharris, author of The Butchering Art

-

"The story of the extraordinary women who ran the 'Suffragettes' Hospital' is visceral, timely, urgent, and spellbinding. Wendy Moore's book is utterly involving and deeply thought-provoking, and all I can do is urge you to read it."Helen Castor, author of She-Wolves

-

"No Man's Land is an extraordinary story, and beautifully told."Anita Anand, author of Sophia