Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

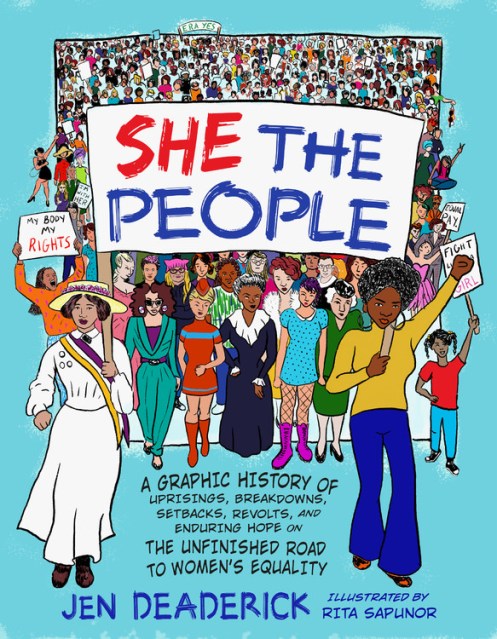

She the People

A Graphic History of Uprisings, Breakdowns, Setbacks, Revolts, and Enduring Hope on the Unfinished Road to Women's Equality

Contributors

Illustrated by Rita Sapunor

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580058711

Price

$17.99Price

$23.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.49 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A sweeping, smart, and smart-ass graphic history of women’s ongoing quest for equality

In March 2017, Nevada surprised the rest of America by suddenly ratifying the Equal Rights Amendment–thirty-five years after the deadline had passed. Hey, better late than never, right? Then, lo and behold, a few months later, Illinois followed suit. Hurrah for the Land of Lincoln!

That left the ERA just one state short of the congressional minimum for ratification. One state–and a legacy of shame–are what stand between American women and full equality.

She the People takes on the campaign for change by offering a cheekily illustrated, sometimes sarcastic, and all-too-true account of women’s evolving rights and citizenship. Divided into twelve historical periods between 1776 and today, journalist, historian, and activist Jen Deaderick takes readers on a walk down the ERA’s rocky road to become part of our Constitution by highlighting changes in the legal status of women alongside the significant cultural and social influences of the time, so women’s history is revealed as an integral part of U.S. history, and not a tangential sideline.

Clever and dynamic, She the People is informative, entertaining, and a vital reminder that women still aren’t fully accepted as equal citizens in America.

Genre:

-

"Fast paced and full to bursting with vivid, raucous figures and stories that have been kept out of our history books for too long, Jen Deaderick's She the People is a remarkable corrective that will broaden readers' views and deepen their understanding of thehistory that has brought us to this moment--and will inspire new approaches to moving forward."Rebecca Traister, New York Times bestselling author of Good and Mad and All the Single Ladies

-

"This isn't women's history; it's history. She the People is a hilarious, brilliant take on the road to equality."Lizzie Skurnick, author of That Should Be a Word