Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

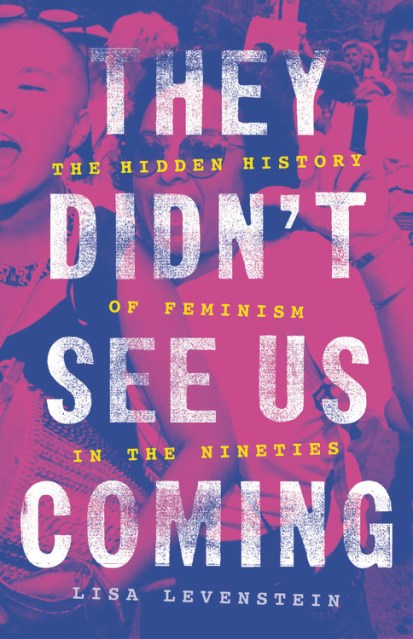

They Didn’t See Us Coming

The Hidden History of Feminism in the Nineties

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465095285

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From an award-winning scholar, a vibrant portrait of a pivotal moment in the history of the feminist movement

From the declaration of the “Year of the Woman” to the televising of Anita Hill’s testimony, from Bitch magazine to SisterSong’s demands for reproductive justice: the 90s saw the birth of some of the most lasting aspects of contemporary feminism. Historian Lisa Levenstein tracks this time of intense and international coalition building, one that centered on the growing influence of lesbians, women of color, and activists from the global South. Their work laid the foundation for the feminist energy seen in today’s movements, including the 2017 Women’s March and #MeToo campaigns.

A revisionist history of the origins of contemporary feminism, They Didn’t See Us Coming shows how women on the margins built a movement at the dawn of the Digital Age.

Genre:

-

"A nuanced history of feminism since the 1990s. Grounding today's fourth-wave feminism in the context of earlier activism, Levenstein locates both mainstream and radical feminism within a broader historical framework, showing how young feminists... are building on foundations laid by the generations before them."Financial Times

-

A Bitch Most Anticipated Book 2020

-

"Lisa Levenstein shows in this lively history how the third-wave feminist movement of the '90s was one that became more diverse, intersectional, and decentered... Through her extensive research, Levenstein paints a compelling picture of the great progress made by the activists of the '90s. She also provides inspiration for feminists today to continue their fight."Bust

-

"The smartest work I've read on how social movements have changed since the sixties. In They Didn't See Us Coming, Lisa Levenstein uses the personal stories of captivating activists to drive the narrative--women you've likely never heard of but will wish you could meet and thank. This is the vital backstory to the massive Women's March of 2017, the #MeToo movement, and the capacious yet unsung organizing that is changing our world for the better."Nancy MacLean, author of Democracy in Chains

-

"A sweeping and beautifully written account of a feminist movement that too many of us assumed had faded away. Lisa Levenstein reveals how a multiracial and global coalition of women kept feminism vibrant and alive in the 1990s. With moving and intimate detail, Levenstein shows that it was these women who made it possible for us to imagine a more just and equitable future today."Heather Ann Thompson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Blood in the Water

-

"Lisa Levenstein's poignant history of the change-makers in 1990s feminism shows how movements are made and sustained. They Didn't See Us Coming is an important and compelling new account that brings this vital activism to life-and encourages us to learn from the work of these women."Daisy Hernández, coeditor of COLONIZE THIS!: Young Women of Color on Today's Feminism

-

"Lisa Levenstein adds a critically important chapter to the history of feminist activism by recovering the powerful intersectional voices of the 1990s. They Didn't See Us Coming unearths the theoretical interventions as well as the nitty-gritty of feminist organizing to showcase the varied and textured, multi-layered and multi-issue praxis of feminism, both globally and locally, that laid the foundation for the recent upsurge in feminism. This book will shift our thinking about the evolution of modern feminism and is essential reading for anyone who cares about feminism or social justice."Premilla Nadasen, author of Household Workers Unite and President of the National Women's Studies Association

-

"Lisa Levenstein offers a refreshing and groundbreaking account of the feminist movements of the 1990s. She foregrounds the global arena and women of color to underscore how intersectional analyses of inequality fundamentally shaped women's movements, ideas, and strategies. This book introduces us to compelling people searching for ways to make a more just society."Judy Wu, author of Radicals on the Road

-

"Lisa Levenstein has written a moving and exciting new history that captures the global roots of today's feminism. They Didn't See Us Coming reveals a thriving and transnational movement bursting forth from the 1990s grounded in the theories and activism of women of color. This remarkable book lifts up the stories of women who blazed their own trail, and together changed the world."Loretta Ross, coauthor of Radical Reproductive Justice

-

"Persuasive... [Levenstein's] revisionist history effectively counters stereotypes of the decade's feminism... Contemporary feminists will be enlightened, while those who entered the movement in the '90s will feel vindicated."Publishers Weekly

-

"An authoritative account of how the feminist movement evolved during the 1990s and beyond... sharp... Levenstein successfully combines well-documented research with personal observations and interviews to create an accessible and informative narrative. Required reading for classes in women's studies."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Levenstein adds nuances that will provide rich space for current feminist theorists, scholars, and activists to dig deeper into feminist history, and its social ramifications in a digital era. A valuable contribution to the history of feminism at its grassroots and global levels..."Library Journal

-

"In this compelling and inspiring book, Levenstein ensures that the feminist groups of the nineties will take their rightful place in women's history."Booklist

-

"We don't tend to think of the 1990s as a high point for feminism... Levenstein wants to uncover a different story..."New Republic

-

"By shining a light on history at the margins, Levenstein shows us that our cultural life is complex, multifaceted. The work done in the 1990s by the activists she interviewed-advocates for a wide spectrum of social causes-laid the foundation for today's feminist energy."Harvard Review