Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

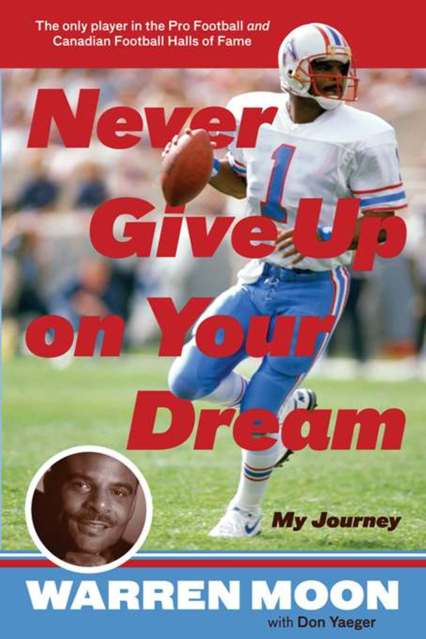

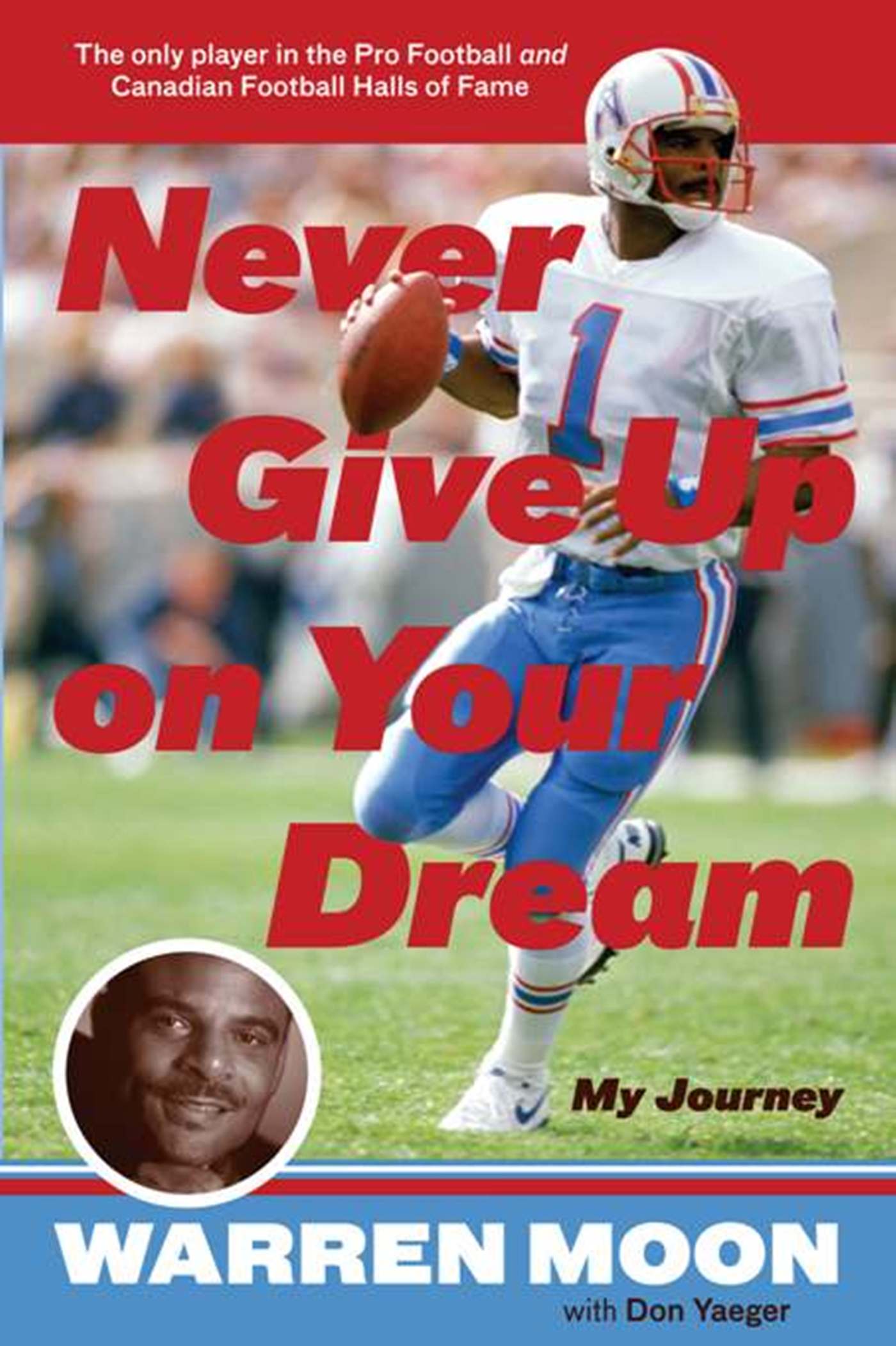

Never Give Up on Your Dream

My Journey

Contributors

By Warren Moon

With Don Yeager

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $16.99 $21.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 21, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In college, he played at the University of Washington, beating the Michigan Wolverines in the Rose Bowl. Undrafted by the NFL, he went to Canada and played for the Edmonton Eskimos, leading his team to five consecutive championships. In 1984, he signed with the Houston Oilers and played for the Oilers, Seattle Seahawks, Minnesota Vikings, and Kansas City Chiefs over his 17-year career.

This is the triumphant story of how Warren Moon overcame all obstacles to become one of the Top 5 quarterbacks of all time.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 21, 2009

- Page Count

- 216 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786749645

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use