By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

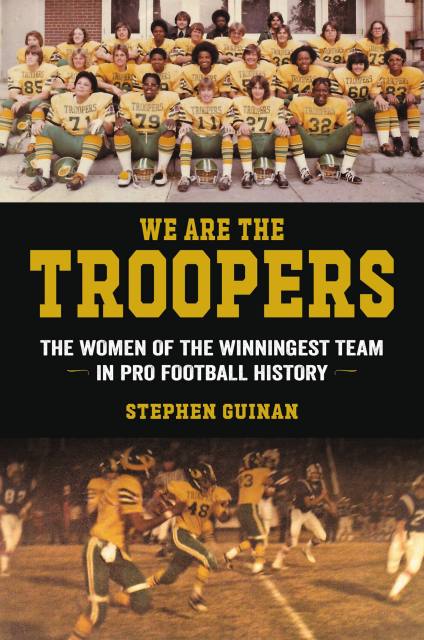

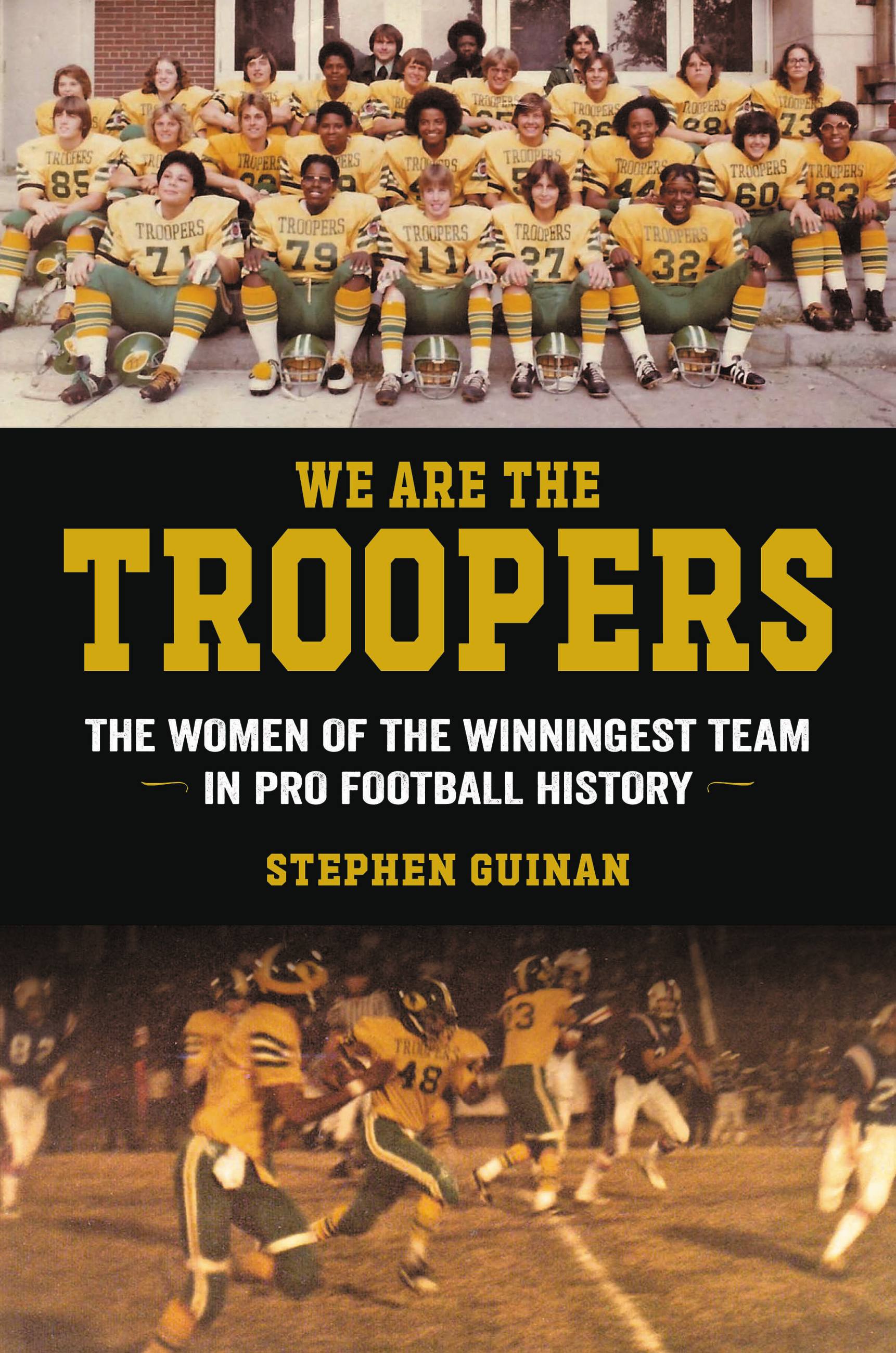

We Are the Troopers

The Women of the Winningest Team in Pro Football History

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 30, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306846939

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 30, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Discover the unlikely story of the Toledo Troopers, the winningest team in the National Women’s Football League, who won seven league championships in the 1970s—and gain full access to the players and key figures in the organization.

Amid a national backdrop of the call to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, the National Women’s Football League was founded as something of a gimmick. However, the league’s star team, the Toledo Troopers, emerged to challenge traditional gender roles and amass a win-loss record never before or since achieved in American football. The players were housewives, factory workers, hairdressers, former nuns, high school teachers, bartenders, mail carriers, pilots, and would-be drill sergeants. Black, white, Latina. Mothers and daughters and aunts and sisters. But most of all, they were athletes who had been denied the opportunity to play a game they were born to play.Before the protests and the lobbyists, before the debates and the amendments, before the marches and the mandates, there was only an obscure advertisement in a local Midwestern paper and those who answered it, women such as Lee Hollar, the only woman working the line at the Libbey glass factory; Gloria Jimenez, who grew up playing sports with her six brothers; and Linda Jefferson, one the greatest, most accomplished athletes in sports history. Stephen Guinan grew up in Toledo pulling for his hometown football team, and—in the innocence of youth—did not realize at the time what a barrier-breaking lost piece of history he was witnessing. We Are the Troopers shines light on forgotten champions who came together for the love of the game.

-

“An absolute treat….The story of the long-forgotten (if ever remembered) Toledo Troopers, a woman’s football team that dominated the land for a good decade. Guinan is a fabulous writer, and his joy dances from page to page.”Jeff Pearlman

-

“We Are The Troopers is the story of a group of game-changing women from all walks of life who came together to leverage the power of sports to influence the gender discussion and inspire their generation and future generations.”Billie Jean King

-

“Stephen Guinan has written an important book detailing a crucial time and place in women’s sports history. I grew up in Toledo following the Troopers. This book is a wonderful walk down memory lane for me, and a compelling story about trailblazing women who broke barriers and inspired a generation of girls and women to follow their dreams.”Christine Brennan, author of Best Seat in the House and Inside Edge

-

"Women's football has been drawn out of the shadows of history to some degree in recent years, but We Are the Troopers breathes true life into that history through its focus on the league's best team, its breakout star Linda Jefferson, and her groundbreaking teammates. By showing us the game through the eyes of the women who played it, Guinan brings us closer to that time and that action than a mere chronicle ever could and ensures that this unique chapter in sports history will never be lost."Craig Calcaterra, author of Rethinking Fandom

-

“Utterly surprising and exhaustively researched, We Are the Troopers manages to be both lovingly nostalgic and reflective of the current moment. This is a story about the American obsession with football that is, at its heart, a story about the stubborn persistence of the American dream.”Michael Weinreb, author of Season of Saturdays: A History of College Football in 14 Games

-

"An essential book on one of the most dominant teams of all time. I'm thankful Guinan has brought the story to light, writing with elegance and urgency to tell the story of the Troopers beautifully. I won't forget this team."Mirin Fader, New York Times bestselling author of Giannis

-

"An incredible story."Buzzfeed

-

“The inspiring, little-known story of a powerful women’s professional football team in the 1970s….In this exciting, informative resurrection of largely forgotten history, Guinan…tells the story of the Toledo Troopers… [and] does a fantastic job of delving into the lives of the women who play…. Fabulous lost sports history for historians and sports fans alike.”Kirkus Reviews (starred)

-

“These women played with passion, broke barriers, and risked ridicule and alienation from their families, not to mention career-ending injuries. Coinciding with the fiftieth anniversary of Title IX and a companion documentary with the same title, this eye-opening account introduces readers to a special sisterhood that made history and defied gender norms.”Booklist

-

“An obscure but significant chapter in American women’s professional sports comes to dazzling life in essayist Guinan’s debut…Feminists and football fans alike will find much to appreciate.”Publishers Weekly

-

“We Are the Troopers is a well-written and engaging ode to these women who made history on the gridiron and in the hearts of every little girl who wondered to what heights they could soar.”G-pop.net

-

“An excellent addition to the field…. Guinan has written an epic saga of the Troopers…. His prose not only tells the story of a football team, but it also grabs the reader and carries them from the formation of the team to its decline…. Guinan writes with the style of a modern-day Grantland Rice…. Guinan’s book should appeal to football fans everywhere. His descriptions of the player’s backstories provide a window, often in the words of the athletes themselves, into a past when women had to struggle to play sports of any kind, let alone football…. We Are the Troopers is a compelling read.”Russ Cawford, USSportHistory.com

-

“Amy Landon’s strong narration anchors this in-depth history of the Toledo Troopers….Landon balances the author’s appreciation for the players’ tenacity and toughness, skill and sacrifice with a clear-eyed examination of the demanding physicality and business sides of the sport.…Landon’s light characterizations emphasize the diverse personalities of the players, including Linda Jefferson, Lee Hollar, and Pam Schwartz, who shined on and off the field. This solid production is a welcome addition to American sports history.”AudioFile (audiobook review)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use