By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

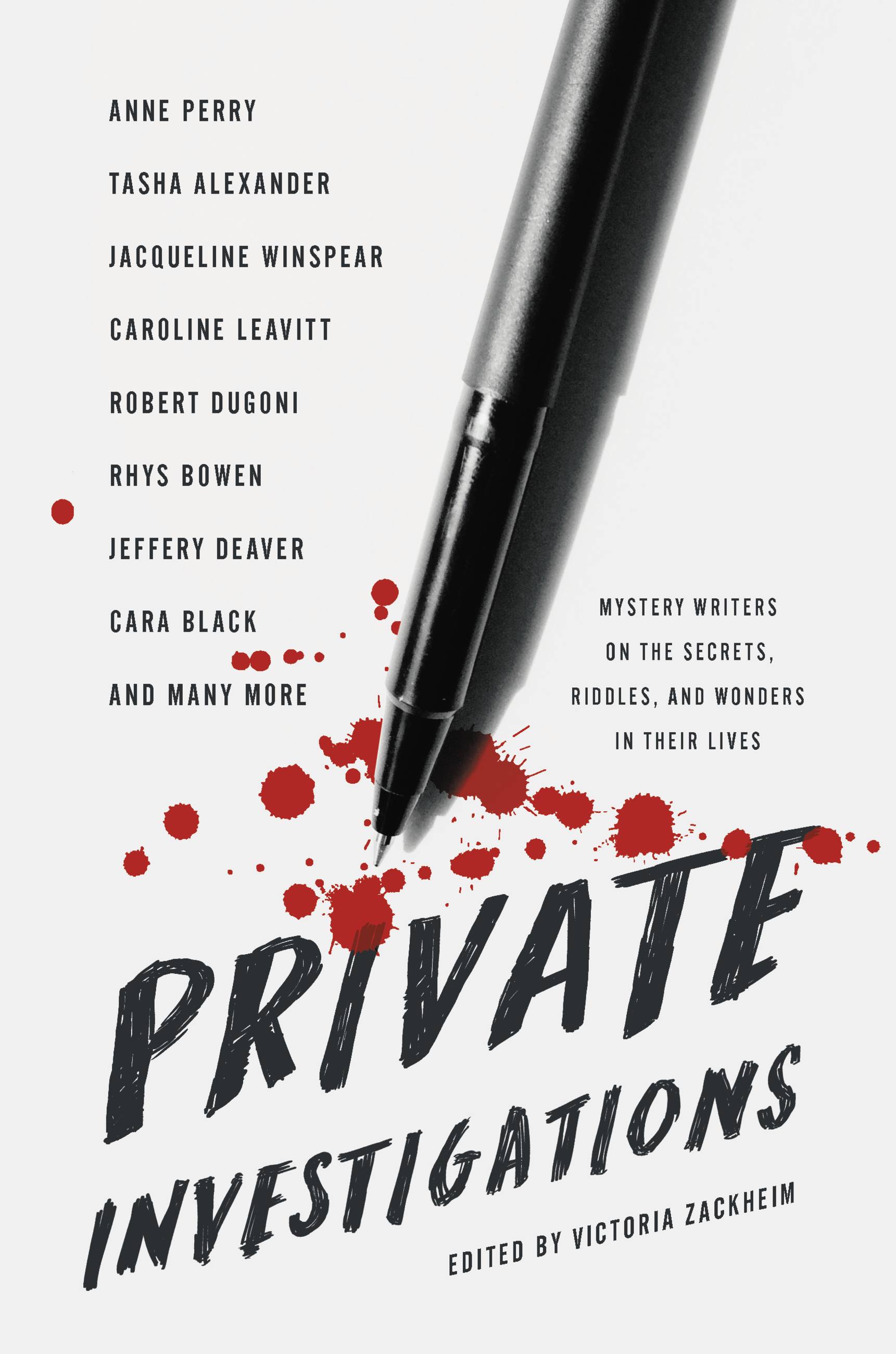

Private Investigations

Mystery Writers on the Secrets, Riddles, and Wonders in Their Lives

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 21, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580059220

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 21, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this thrilling anthology, bestselling mystery writers abandon the cloak of fiction to investigate the suspenseful secrets in their own lives.

For many of us, a good, heart-pounding mystery is the perfect escape from real-world confusion and chaos. But what about the writers who create those stories of suspense and intrigue? How do our favorite novelists cope with our perplexing world, and what mysteries keep them up at night?

In Private Investigations, twenty fan-favorite mystery writers share first-person tales of mysteries they’ve encountered at home and in the world. Caroline Leavitt regales us with a medical mystery, recounting a time when she lost her voice and doctors couldn’t find a cure, Martin Limón travels back to his military stint in Korea to grapple with the crimes of war, Anne Perry ponders the magical powers of stories conjured from writers’ imaginations, and more.

Exploring all the tropes of the genre — from haunted houses and elusive perpetrators to regrouping after missed signals have derailed them — these writers’ true tales show just how much art imitates life, and how, ultimately, we are all private investigators in our own real-world dramas.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use