By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

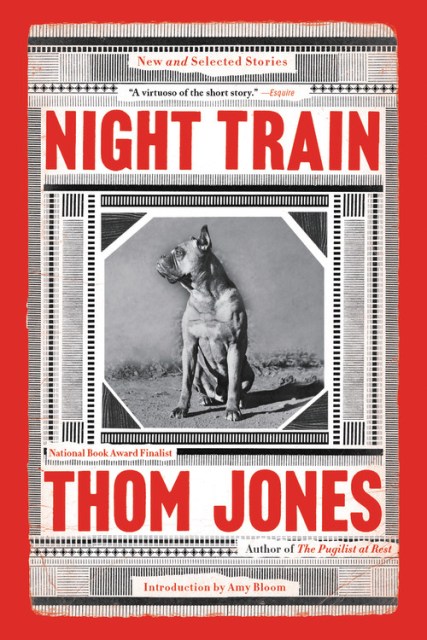

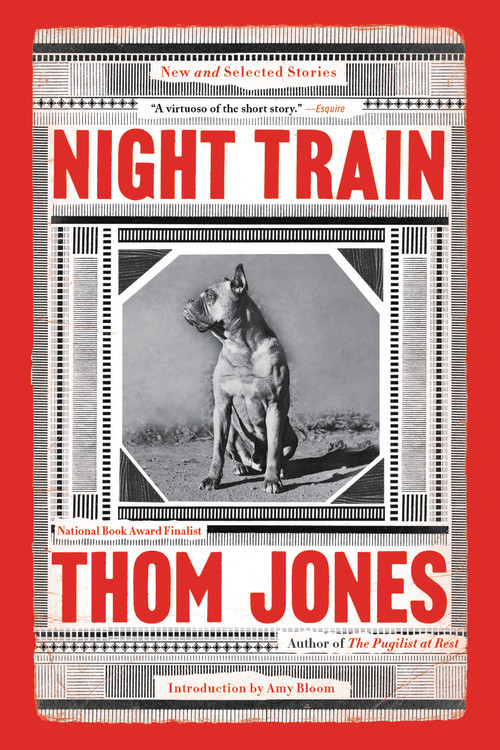

Night Train

New and Selected Stories

Contributors

By Thom Jones

Introduction by Amy Bloom

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 8, 2019

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316449366

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 8, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A posthumous and definitive collection of new and selected stories by “virtuoso of the short story” (Esquire) and National Book Award finalist Thom Jones.

This scorching collection from award-winning author Thom Jones features his best new short fiction alongside a selection of outstanding stories from three previous books. Jones’s stories are full of high-octane, prose-drunk entertainment. His characters are grifters and drifters, rogues and ne’er-do-wells, would-be do-gooders whose human frailties usually get the better of them.

Some are lovable, others are not, but each has an indelible and irresistible voice. They include Vietnam soldiers, amateur boxers, devoted doctors, strung-out advertising writers, pill poppers and veterans of the psych ward, and an unforgettable adolescent DJ radio host, among others.

The stories here are excursions into a unique world that veers between abject desperation and fleeting transcendence. Perhaps no other writer in recent memory could encapsulate in such short spaces the profound and the devastating, the poignant and the hallucinatory, with such an exquisite balance of darkness and light. Jones’s fiction reveals again and again the resilience and grace of characters who refuse to succumb. In stories that can at once delight us with their wicked humor and sting us with their affecting pathos, Night Train perfectly captures the essence of this iconic American master, showcasing in a single collection the breadth of power of his inimitable fiction.

This scorching collection from award-winning author Thom Jones features his best new short fiction alongside a selection of outstanding stories from three previous books. Jones’s stories are full of high-octane, prose-drunk entertainment. His characters are grifters and drifters, rogues and ne’er-do-wells, would-be do-gooders whose human frailties usually get the better of them.

Some are lovable, others are not, but each has an indelible and irresistible voice. They include Vietnam soldiers, amateur boxers, devoted doctors, strung-out advertising writers, pill poppers and veterans of the psych ward, and an unforgettable adolescent DJ radio host, among others.

The stories here are excursions into a unique world that veers between abject desperation and fleeting transcendence. Perhaps no other writer in recent memory could encapsulate in such short spaces the profound and the devastating, the poignant and the hallucinatory, with such an exquisite balance of darkness and light. Jones’s fiction reveals again and again the resilience and grace of characters who refuse to succumb. In stories that can at once delight us with their wicked humor and sting us with their affecting pathos, Night Train perfectly captures the essence of this iconic American master, showcasing in a single collection the breadth of power of his inimitable fiction.

-

"There's a feeling of magic at work, as though Jones was an oracle channeling the voices of his crazed, raucously funny, deeply damaged gallery of characters . . . It's impossible not to marvel at the urgency of these stories. Reviewers like to say that good writing feels alive, but living things are subject to the laws of decay, and the miracle of literature is that the truly great stuff has no half-life. It doesn't fade or stale or ossify . . . Immortality is too much to demand of anyone's work, of course, and yet there are moments in Jones's stories where the writing seems capable of transcending the forces of destruction it so unforgettably evokes."Sam Sacks, Wall Street Journal

-

"What keeps drawing me into Jones's stories is the precision of his language . . . Jones knew that the short story has to present a bang rather than build up to it, as the novel does . . . Like Alice Munro, he was able to pour thoughts and feelings into a small mold and boil them down until they had the complexity of a novel but much more sharpness . . . His stories show you states of mind that you may never have experienced. They are intensely lively and down to earth; adventurous, often harsh, but subtly self-effacing; both a generational portrait and a self-portrait of one of the strangest writers of our times."Jane Smiley, Guardian

-

"Thom Jones was a master of the short story, a master of the same brand of incandescent, hallucinatory creation of voices that made his contemporary Denis Johnson famous. It is a great gift for all of us to have the best of his work, new and old, here in one place. Night Train will be an amazing discovery for anyone who cares about literature."Philipp Meyer, Pulitzer Prize finalist and New York Times bestselling author of The Son

-

"Thom Jones wrote like his hands were on fire. The stories collected in Night Train are radioactive with soul, bleak humor, and savage truth. This book affirms Jones's standing as one of short fiction's timeless masters."Wells Tower, author of Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned

-

"Jones has a distinctive voice that comes through often in raw, direct, almost driven language, as if he felt short of time. His mostly blue-collar characters were often fiercely alive, whether he was writing about soldiers, boxers, victims, or miscreants...At his best he offers a poignant, compelling view of the human condition."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"A master of the form... Jones' style is characterized by compassion, surprising humor, and his characters and their determination to survive. This superb volume, richly introduced by Amy Bloom, will renew appreciation of Jones' literary power."Booklist (starred review)

-

"A virtuoso of the short story."Adrienne Westenfeld, Esquire

-

"The stories in this collection are sometimes profane, sometimes hilarious, and always brilliant. Thom Jones was an extraordinary writer."Kevin Powers, National Book Award finalist and New York Times bestselling author of A Shout in the Ruins and The Yellow Birds

-

"Thom Jones is a one of a kind real deal genius. I would scream it from a skyscraper if it would help, I'd sell his books door to door just to let people know, and if I had enough copies I'd break into every motel and hotel I came across and leave a copy. He's one of America's great short story masters.'"Willy Vlautin, author of Lean on Pete and Don't Skip Out On Me

-

"Like Denis Johnson or Barry Hannah, Thom Jones's fiction thrusts you into nerve-racking proximity with the wild, the broken and the sick. His stories are so funny and so sad, and too-little read these days. If you don't know his work, this is a great place to start. If you do, you'll be glad of the chance to tune in to the final transmissions from a unique writer."ChrisPower, author of Mothers

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use