By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

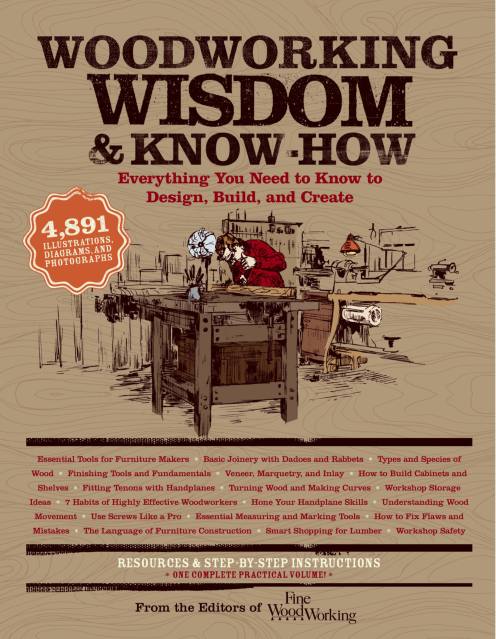

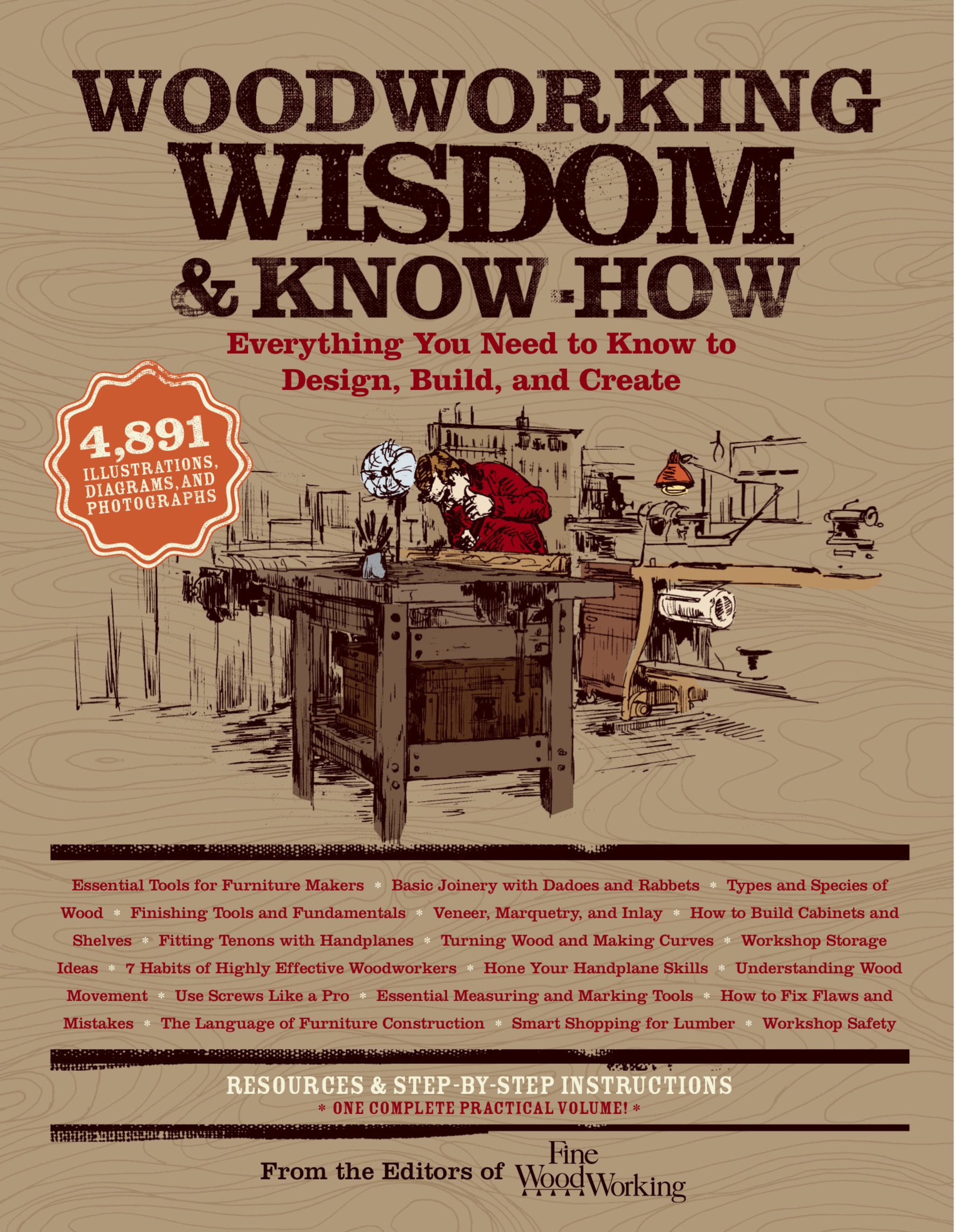

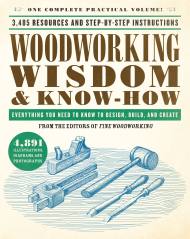

Woodworking Wisdom & Know-How

Everything You need to Design, Build and Create

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 17, 2014

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781603764124

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $27.99 $35.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 17, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Woodworking Wisdom & Know-How is the essential go-to book for every woodworking project imaginable, from building kitchen cabinets to refinishing a deck, from the vast cache of Fine Woodworking‘s projects and advice. Topics addressed in this book include:

- Types of Wood

- Building a Workshop

- Working and Finishing Wood

- Design and Styles

- Small and Large Projects

Each section is further broken down into chapters that cover specific skills, projects, and crafts for both the beginner and the advanced woodworker. Featuring step-by-step instructions, troubleshooting guides and discussions, and an appendix of essential resources for supplies, tools, and materials, Woodworking Wisdom & Know-How is your one-stop-shop for trusted, tried, and true woodworking advice.

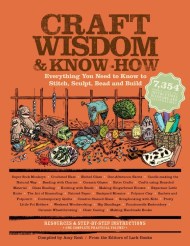

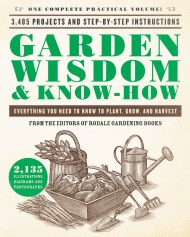

This book is also a part of the Know-How series which includes other titles such as:

- Country Wisdom & Know-How

- Natural Healing Wisdom & Know-How

- Craft Wisdom & Know-How

- Garden Wisdom & Know-How

Genre:

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use