By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

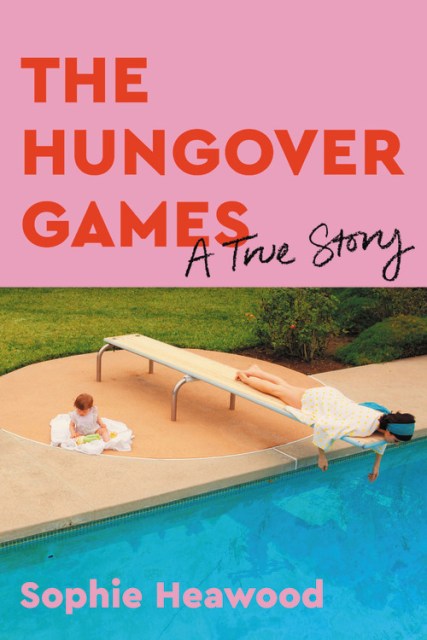

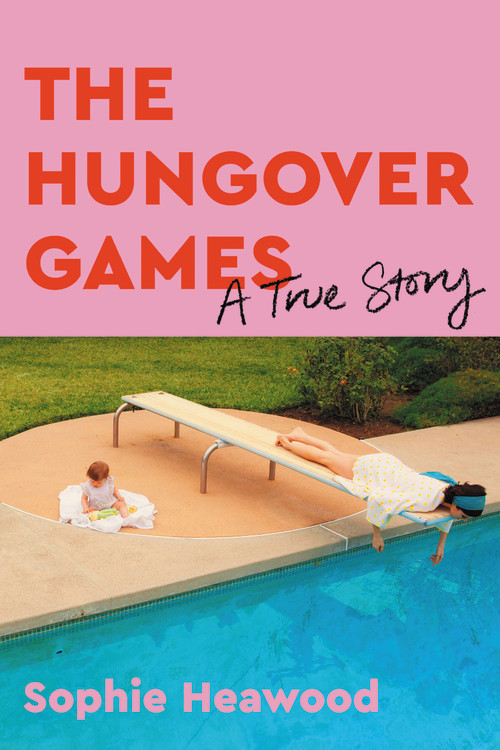

The Hungover Games

A True Story

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316499064

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This “funny, dark, and true” (Caitlin Moran) memoir is Bridget Jones’s Diary for the Fleabag generation: What happens when you have an unplanned baby on your own in your mid-thirties before you’ve worked out how to look after yourself, let alone a child?

This is the story of one woman’s adventures in single motherhood. It’s about what happens when Mr. Right isn’t around so you have a baby with Mr. Wrong, a touring musician who tells you halfway through your pregnancy that he’s met someone else, just after you’ve given up your LA life and moved back to England to attempt some kind of modern family life with him.

So now you’re six months along, sleeping on a friend’s sofa in London, and waking up in the morning to a room full of taxidermied animals who seem to be staring at you. The Hungover Games about what it’s like raising a baby on your own when you’re more at home on the dance floor than in the kitchen. It’s about how to invent the concept of the two-person family when you grew up in a traditional nuclear unit of four, and your kid’s friends all have happily married parents too, and you are definitely not, in any way, ticking off the days until all those lovely couples get divorced.

Unflinchingly honest, emotionally raw, and surprisingly sweet, The Hungover Games is the true story of what happens if you’ve been looking for love your whole life and finally find it where you least expect it.

A Sunday Times Bestseller (UK)

A Sunday Times Bestseller (UK)

-

"Raw and funny, Heawood's memoir celebrates the messiness of life and motherhood with boldness, panache, and unexpected moments of real poignancy. An uncensored and eccentric delight."Booklist

-

"Finally the book that single mothers across the globe have been waiting for. . . . Funny, dark and true."Cailtin Moran

-

"Single motherhood gets a caustic spin in this intercontinental memoir. Sophie Heawood revisits the time her life fell apart: when she left L.A. for her native England while pregnant, and her musician boyfriend walked out on her."Entertainment Weekly

-

"Sophie has the ability to write as if she's talking only to you, in moments of humour and pathos. She makes you feel like you're not on your own. I always feel both inspired and comforted after reading her work. She has a voice as a solo parent that I don't think is represented in the world today. I am, and will always be, her biggest fan."James Corden

-

"Unflinching yet comic."Cosmopolitan (UK)

-

"The Hungover Games deftly explores expectations of modern womanhood through a beautiful, wild, painfully honest, hilarious and sometimes heartbreaking story. Full of adventure and awe, Sophie Heawood has written a soulful, truthful homage to a life lived with appetite, intensity and wonder."Dolly Alderton

-

"It's a deeper, funnier, realer, more poignant Bridget Jones. I have never read a more accurate account of what it feels like to be a parent, especially a single one."Philippa Perry

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use