By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

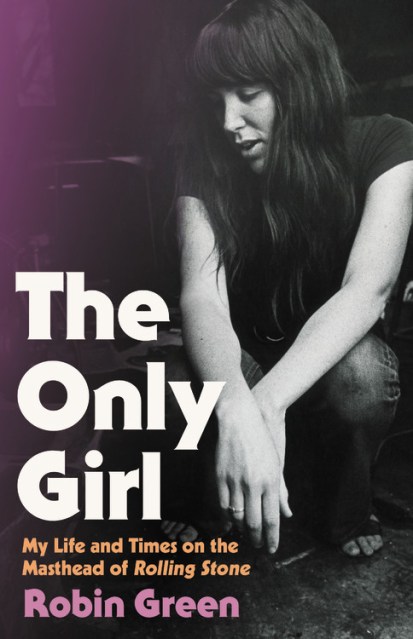

The Only Girl

My Life and Times on the Masthead of Rolling Stone

Contributors

By Robin Green

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 21, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316440028

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 21, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A raucous and vividly dishy memoir by the only woman writer on the masthead of Rolling Stone Magazine in the early Seventies.

In 1971, Robin Green had an interview with Jann Wenner at the offices of Rolling Stone magazine. She had just moved to Berkeley, California, a city that promised “Good Vibes All-a Time.” Those days, job applications asked just one question: “What are your sun, moon and rising signs?” Green thought she was interviewing for a clerical job like the other girls in the office, a “real job.” Instead, she was hired as a journalist.

With irreverent humor and remarkable nerve, Green spills stories of sparring with Dennis Hopper on a film junket in the desert, scandalizing fans of David Cassidy and spending a legendary evening on a water bed in Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s dorm room. In the seventies, Green was there as Hunter S. Thompson crafted Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and now, with a distinctly gonzo female voice, she reveals her side of that tumultuous time in America.

Brutally honest and bold, Green reveals what it was like to be the first woman granted entry into an iconic boys’ club. Pulling back the curtain on Rolling Stone magazine in its prime, The Only Girl is a stunning tribute to a bygone era and a publication that defined a generation.

In 1971, Robin Green had an interview with Jann Wenner at the offices of Rolling Stone magazine. She had just moved to Berkeley, California, a city that promised “Good Vibes All-a Time.” Those days, job applications asked just one question: “What are your sun, moon and rising signs?” Green thought she was interviewing for a clerical job like the other girls in the office, a “real job.” Instead, she was hired as a journalist.

With irreverent humor and remarkable nerve, Green spills stories of sparring with Dennis Hopper on a film junket in the desert, scandalizing fans of David Cassidy and spending a legendary evening on a water bed in Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s dorm room. In the seventies, Green was there as Hunter S. Thompson crafted Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and now, with a distinctly gonzo female voice, she reveals her side of that tumultuous time in America.

Brutally honest and bold, Green reveals what it was like to be the first woman granted entry into an iconic boys’ club. Pulling back the curtain on Rolling Stone magazine in its prime, The Only Girl is a stunning tribute to a bygone era and a publication that defined a generation.

-

"She writes unsparingly of her frailties, her fixations, the honest appetites of an explorer in a fragmenting America. Brave survivor of the psychedelic wars, she came, she saw, she conquered."USA Today

-

"A dishy memoir about life as the first woman on the masthead at Rolling Stone magazine during the sex and drugs heyday of the 1970s."New York Times

-

"They say if you remember the '60s, you weren't there. But Robin Green was. She remembers the '70s, too, and all that followed. And what's more, in "The Only Girl," she names names... lately, Green's been thinking back on those hippie San Francisco days again. Her trips to Big Sur, beautifully crazy friends, and her own flower-child belief that anything -- absolutely anything -- was possible. Turns out, she was right."New York Daily News

-

"a stunning tribute to a bygone era and a publication that defined a generation,"Red Carpet Crash

-

"a must-read for anyone who has ever been or felt like, well, the only girl in the room."Hello Giggles

-

"In this candid memoir, she shares how she earned a reputation as a bitch, what it was like working alongside the intimidating Annie Leibovitz and witnessing the drug-fueled ravings of Hunter S. Thompson, and why she was fired over a Kennedy story...Filled with plenty of sex, drugs, and some rock 'n' roll, this offers a one of-a-kind perspective on the people behind a cultural phenomenon."Booklist

-

"The Only Girl's vigor comes from her blunt acknowledgment of the diffidence she faced early in her career. To follow her path to being paid, published, and praised amid many tribulations proves both a solace and great reward."Zyzzyva

-

"A lusty, reflective, score-settling memoir from the woman who steered a chaotic career course between Rolling Stone and The Sopranos...Green's memoir is both a solid insider's account and a happy-go-lucky, lifelong coming-of-age story."Kirkus

-

"With humor and candid self-reflection, the author details her struggles after being fired from Rolling Stone...Reading like a real-life road novel, Green's memoir is a must for aspiring writers."Library Journal

-

"Brutally honest, Ms. Green writes about what it was like to be the first woman granted entry into an iconic boys club."WNYC

-

"[A] funny, candid memoir...Green paints a vivid picture of being at the epicentre of the new rock'n'roll bohemian culture with the Rolling Stone crowd."Guardian

-

"Entertaining, page-turning, and scorchingly candid new memoir."No Depression

-

"Compulsively readable, laugh out loud funny and beautifully crafted. I ate up every word. If you thought they had more fun back then, this book will prove that you were right."Ruth Reichl, bestselling author of My Kitchen Year

-

"Robin has written a frank, witty and loving memoir about growing up in the milieu of the seventies at Rolling Stone. Her honesty and insight brought all those times back, some of RS's wildest and wackiest early days."Jann Wenner, Co-Founder and Publisher of Rolling Stone

-

"A funny, frank, powerful and ultimately moving memoir by an extraordinary writer who didn't merely roll with the Zeitgeist but remade it in her own image."T.C. Boyle, author of The Harder They Come and The Terranauts

-

"This isn't a memoir recollected in tranquility. It doesn't 'capture' an experience. It animates a specific time and place - - making it jump off the page so it smacks you in the face. If you didn't live it, you do now. If you did, it's déjà vu all over again. Robin Green stares down her life in the clarifying light of truth. Her fearlessness and reckless honesty give her story an aching power, poignancy, and immediacy you won't soon forget."Joshua Brand, writer and producer of St. Elsewhere, Northern Exposureand The Americans

-

"Robin Green broke ground for women as part of two media revolutions-Rolling Stone's reimagining of the magazine and the new era for television ushered in by The Sopranos. With The Only Girl, she offers sharp and striking scenes of a culture in transition, creating a vivid sense of both the thrilling possibilities and the heartbreaking limitations of the times."Alan Light, former Editor-in-Chief of Vibe and Spinmagazines and author of Let's Go Crazy: Prince and the Making of Purple Rain

-

"Only girl on the masthead? And in the room! And still standing! And with cojones! Green has written a straight-talking, utterly indiscrete, deliciously shocking story about being in the right place at the right time pretty much all the time."Bill Buford, journalist and author of Among the Thugs and Heat

-

"Her prose has a freewheeling, informal quality, summoning some moments vividly."Financial Times

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use