Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

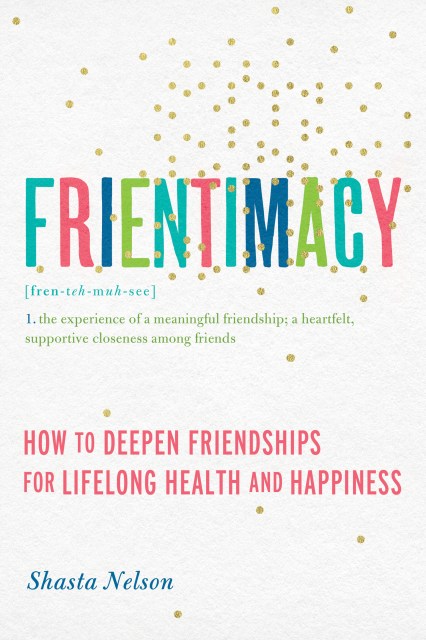

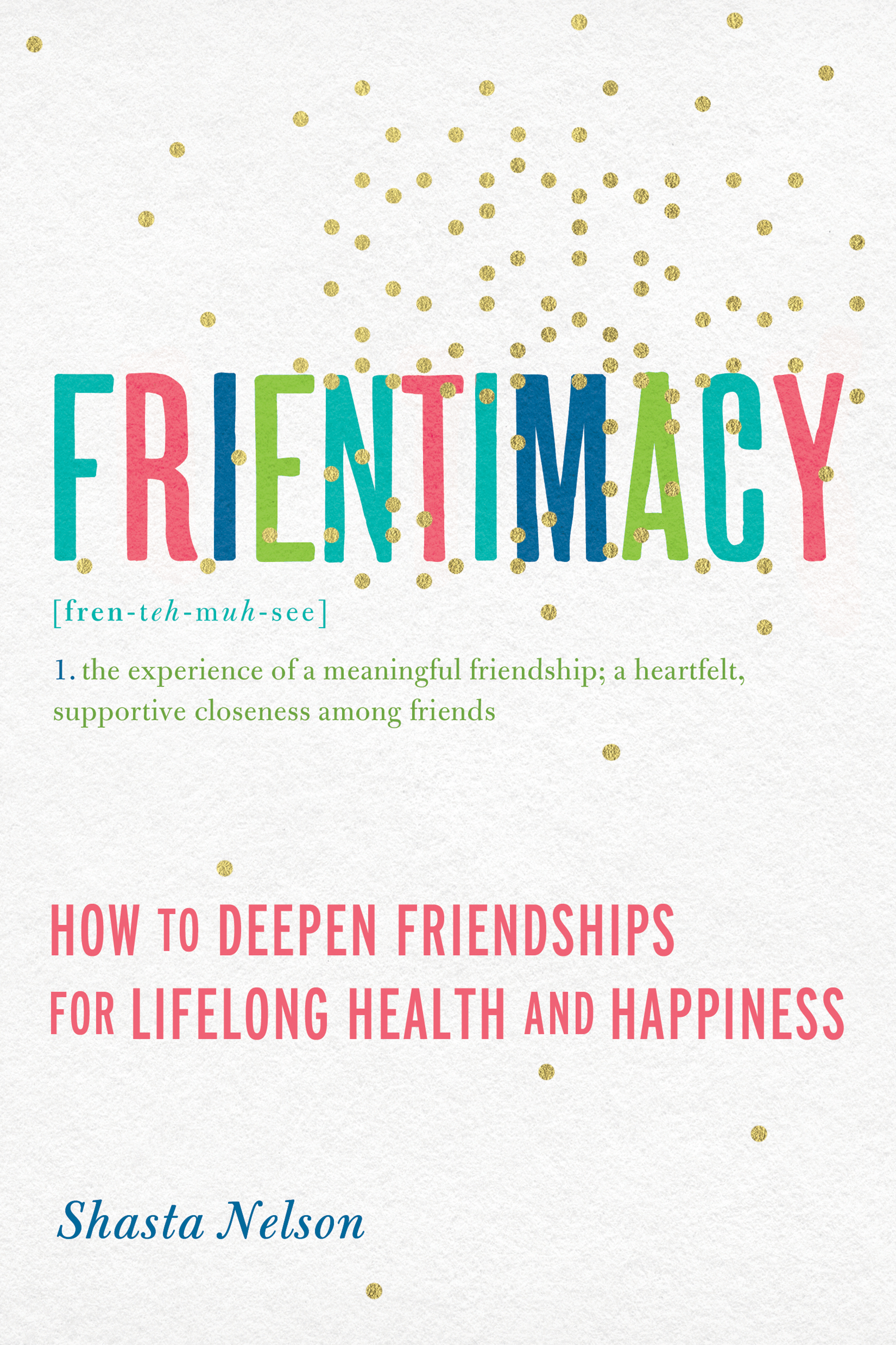

Frientimacy

How to Deepen Friendships for Lifelong Health and Happiness

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 1, 2016

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056083

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 1, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Shasta explores the most common complaints and conflicts facing female friendships today, and lays out strategies for overcoming these pitfalls to create deeper, supportive relationships that last for the long-term. Shasta is the founder of girlfriendcircles.com, a community of women seeking stronger, more fulfilling friendships, and the author of Friendships Don’t Just Happen. In Frientimacy, she teaches readers to reject the impulse to pull away from friendships that aren’t instantly and constantly gratifying.

With a warm, engaging, and inspiring voice, she shows how friendships built on dedication and commitment can lead to enriched relationships, stronger and more meaningful ties, and an overall increase in mental health. Frientimacy is more than just a call for deeper connection between friends; it’s a blueprint for turning simple friendships into true bonds and for the meaningful and satisfying relationships that come with them.