By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

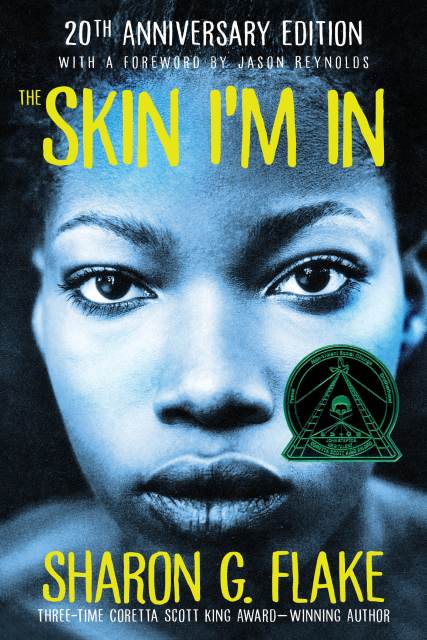

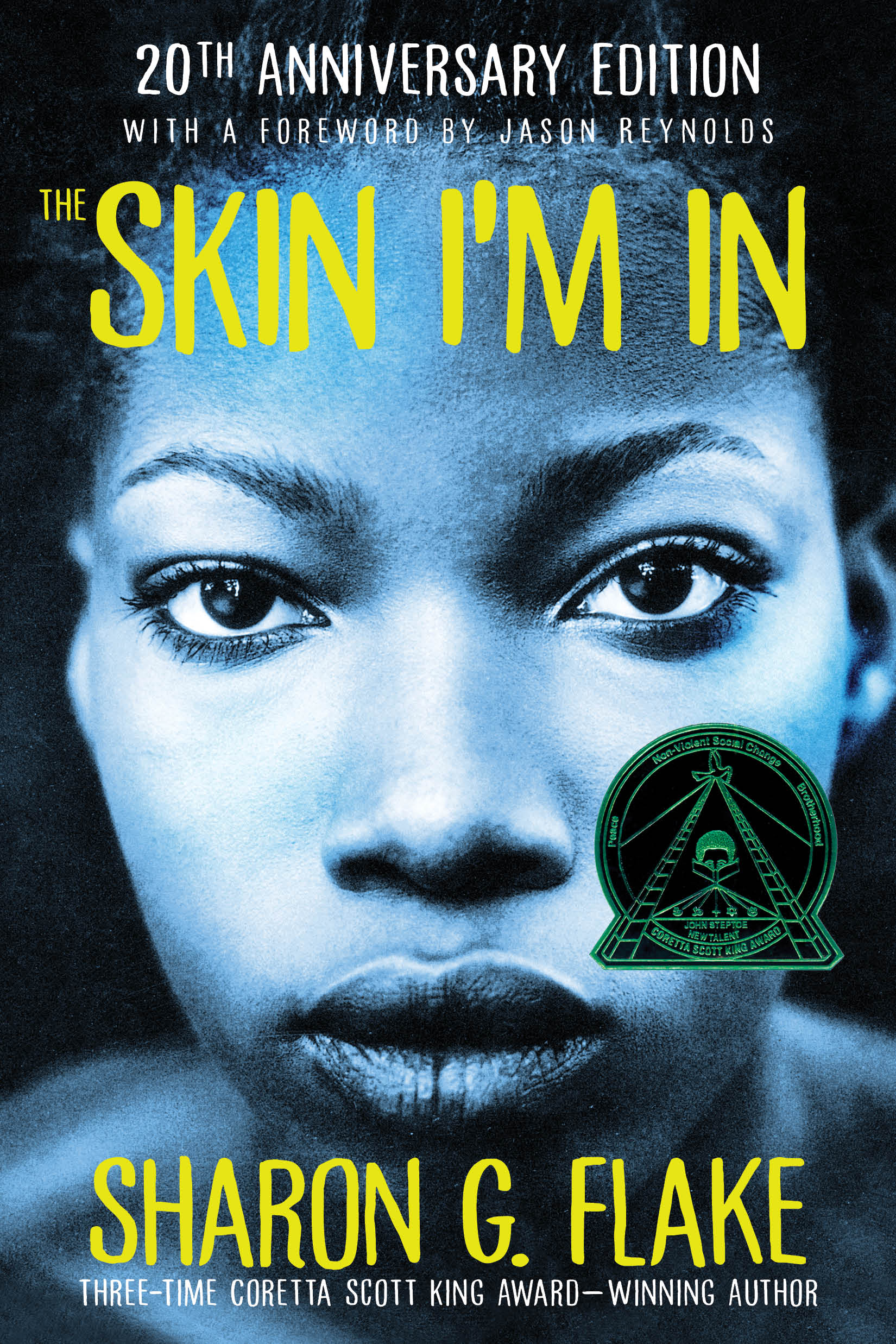

The Skin I’m in

Contributors

By Sharon Flake

Foreword by Jason Reynolds

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 1, 2009

- Page Count

- 176 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781423132516

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 1, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Winner of the Coretta Scott King award

Sharon Flake's award-winning, empowering debut novel follows one girl's struggle toward self acceptance, no matter what the world throws her way. Includes a foreword by bestselling, award-winning author Jason Reynolds!

Maleeka suffers every day from the taunts of the other kids in her class. If they're not getting at her about her homemade clothes or her good grades, it's about her dark, black skin. Maleeka does whatever she can to try and fit in and fly under the radar. But it's never enough.

When a new teacher, whose face is blotched with a startling white patch, starts at their school, Maleeka can see there is bound to be trouble for her too. But the new teacher's attitude surprises Maleeka. Miss Saunders loves the skin she's in. Can Maleeka learn to do the same?

★ "Flake's debut novel will hit home." —Publishers Weekly, starred review

Sharon Flake's award-winning, empowering debut novel follows one girl's struggle toward self acceptance, no matter what the world throws her way. Includes a foreword by bestselling, award-winning author Jason Reynolds!

Maleeka suffers every day from the taunts of the other kids in her class. If they're not getting at her about her homemade clothes or her good grades, it's about her dark, black skin. Maleeka does whatever she can to try and fit in and fly under the radar. But it's never enough.

When a new teacher, whose face is blotched with a startling white patch, starts at their school, Maleeka can see there is bound to be trouble for her too. But the new teacher's attitude surprises Maleeka. Miss Saunders loves the skin she's in. Can Maleeka learn to do the same?

★ "Flake's debut novel will hit home." —Publishers Weekly, starred review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use