Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

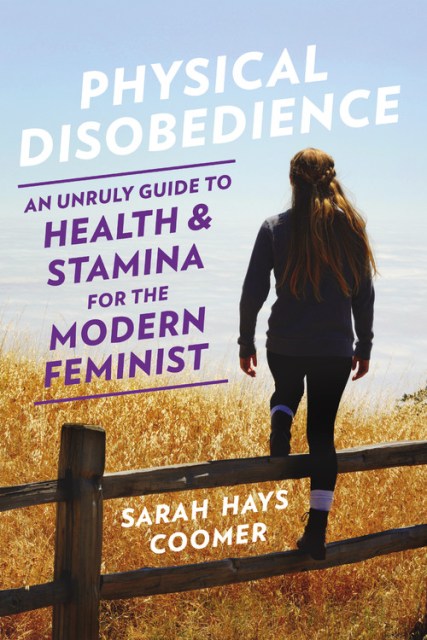

Physical Disobedience

An Unruly Guide to Health and Stamina for the Modern Feminist

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 21, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580057745

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 21, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Even as a wave of renewed feminism swells, too many women continue to starve, stuff, overwork, or neglect our bodies in pursuit of paper-thin ideals. “Fitness” has been co-opted by the beauty industry. We associate it with appearance when we should associate it with power.

Grounded in advocacy with a rowdy, accessible spirit, Physical Disobedience asserts that denigrating our bodies is, in practice, an act of submission to inequality. But when we strengthen ourselves — taking broad command of our individual physicality — we reclaim our authority and build stamina for the literal work of activism: the protests, community service, and emotional resilience it takes to face the news and stay engaged.

Physical Disobedience introduces a breathtaking new perspective on wellness by encouraging nonviolence toward our bodies, revitalizing them through diet and exercise, fashion and social media, alternative therapies, music, and motherhood. The goal is no longer to keep our bodies in check. The goal is to ignite them, to set them free, and have a mighty fine time doing it.