Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

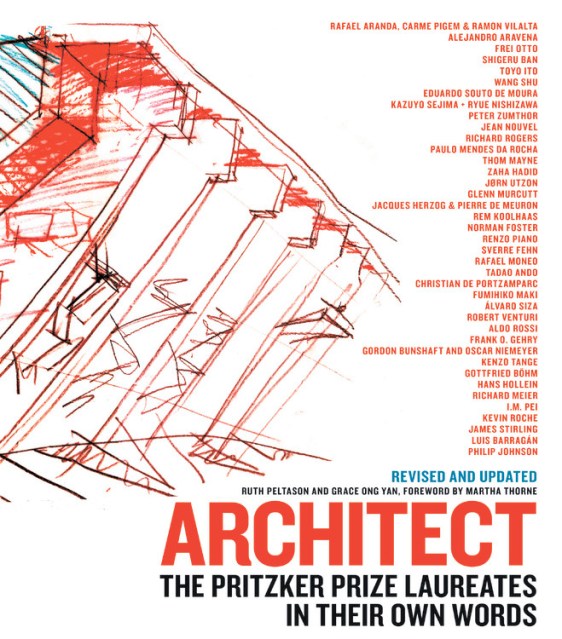

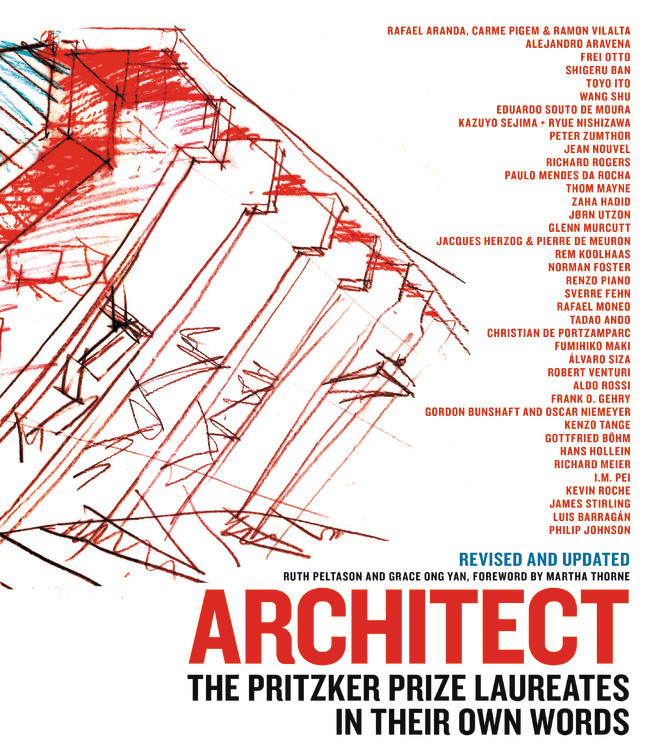

Architect

The Pritzker Prize Laureates in Their Own Words

Contributors

Edited by Ruth Peltason

Edited by Grace Ong Yan

Formats and Prices

Price

$60.00Price

$80.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover (New edition) $60.00 $80.00 CAD

- ebook (New edition) $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Pritzker Prize is the most prestigious international prize for architecture. Architect includes all 42 recipients of the Pritzker Prize, and captures in pictures and their own words their awe-inspiring achievements. Organized in reverse chronological order by laureate each chapter features four to six of the architect’s major works, including museums, libraries, hotels, places of worship, and more. The text, culled from notebooks, interviews, articles, and speeches illuminates the architects’ influences and inspirations, personal philosophy, and aspirations for his own work and the future of architecture. The book includes More than 1000 stunning photographs, blueprints, sketches, and CAD drawings.Architect offers an unprecedented view into the minds of some of the most creative thinkers, dreamers, and builders of the last three decades and reveals that buildings are political, emotional, and spiritual.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316505055

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use