Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

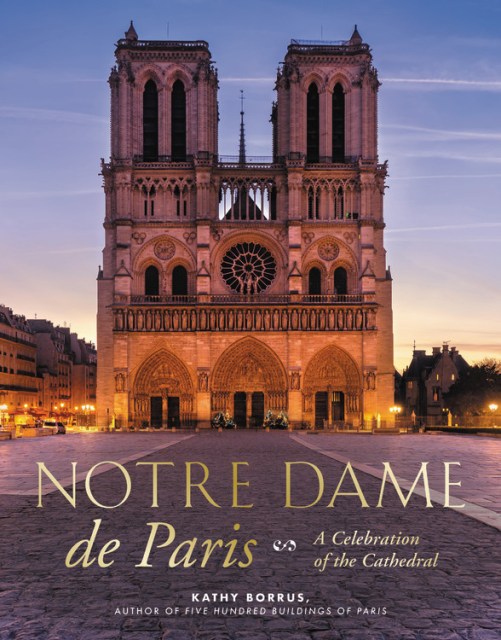

Notre Dame de Paris

A Celebration of the Cathedral

Contributors

By Kathy Borrus

Formats and Prices

Price

$25.00Price

$25.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $25.00 $25.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On April 15, 2019, the world looked on in horror as the Notre Dame Cathedral was nearly destroyed in a devastating fire. Notre Dame de Paris: A Celebration of the Cathedraloffers a fascinating look back at nearly nine centuries of this landmark building that has stood as silent witness to some of the most important events in human history.

A marvel of Gothic architecture, the cornerstone of Notre Dame Cathedral was laid in 1163, and construction was completed in 1345. For almost nine centuries it has served as a house of worship and refuge-a stalwart soldier that has survived wars and revolutions, hosted royal weddings, coronations, and funerals, and inspired Victor Hugo’s literary classic The Hunchback of Notre Dame. With the cathedral wounded but still standing, the world now watches as the rebuilding process gets underway. Notre Dame de Paris: A Celebration of the Cathedralchronicles the history of this landmark building, from its impressive architecture and collection of priceless artifacts to its presence during major world historical events. Through gorgeous, striking, and sometimes rarely seen archival photographs, Notre Dame de Paris: A Celebration of the Cathedralreminds us all why this building has become an unofficial wonder of the world, lodged in the hearts and minds of people around the globe.

A marvel of Gothic architecture, the cornerstone of Notre Dame Cathedral was laid in 1163, and construction was completed in 1345. For almost nine centuries it has served as a house of worship and refuge-a stalwart soldier that has survived wars and revolutions, hosted royal weddings, coronations, and funerals, and inspired Victor Hugo’s literary classic The Hunchback of Notre Dame. With the cathedral wounded but still standing, the world now watches as the rebuilding process gets underway. Notre Dame de Paris: A Celebration of the Cathedralchronicles the history of this landmark building, from its impressive architecture and collection of priceless artifacts to its presence during major world historical events. Through gorgeous, striking, and sometimes rarely seen archival photographs, Notre Dame de Paris: A Celebration of the Cathedralreminds us all why this building has become an unofficial wonder of the world, lodged in the hearts and minds of people around the globe.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2019

- Page Count

- 128 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762497119

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use