Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Help! For Writers

210 Solutions to the Problems Every Writer Faces

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$10.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $10.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 21, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

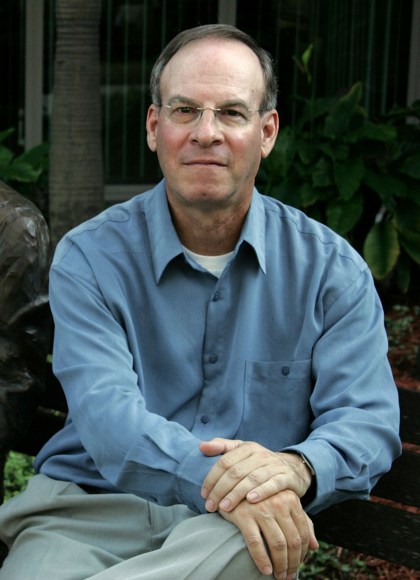

In Help! For Writers, Roy Peter Clark presents an “owner’s manual” for writers, outlining the seven steps of the writing process, and addressing the 21 most urgent problems that writers face. In his trademark engaging and entertaining style, Clark offers ten short solutions to each problem. Out of ideas? Read posters, billboards, and graffiti. Can’t bear to edit yourself? Watch the deleted scenes feature of a DVD, and ask yourself why those scenes were left on the cutting-room floor. Help! For Writers offers 210 strategies to guide writers to success.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 21, 2011

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316192750

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use