Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

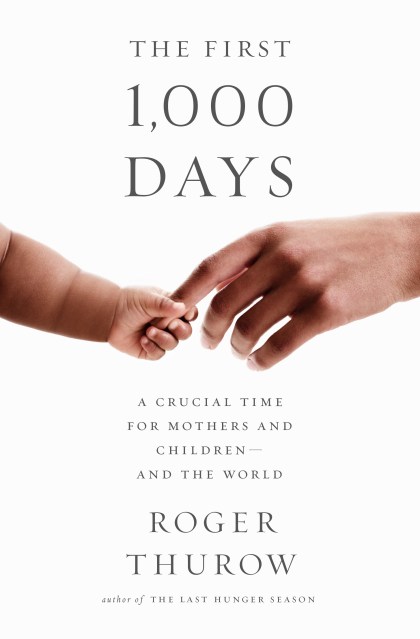

The First 1,000 Days

A Crucial Time for Mothers and Children -- And the World

Contributors

By Roger Thurow

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 3, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395861

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Your child can achieve great things.” A few years ago, pregnant women in four corners of the world heard those words and hoped they could be true; among them, Esther in rural Uganda, Jessica in a violence-scarred Chicago neighborhood, Shyamkali in a low-caste Indian village, and Maria Estella in Guatemala’s western highlands.

Greatness was an audacious thought, but the women had new cause to be hopeful: they were participating in an unprecedented international initiative focused on providing proper nutrition during the first 1,000 days of their children’s lives, beginning with their own pregnancies. The 1,000 Days movement, a response to recent, devastating food crises and new research on the economic and social costs of childhood hunger and stunting, has the power to transform the lives of mothers and children, and ultimately the world. In this inspiring and at times heartbreaking book, Roger Thurow takes us into the lives of families on the forefront of the movement with an intimate narrative that illuminates the science, economics, and politics of malnutrition, charting the exciting progress and formidable challenges of this global effort.

-

Malnutrition is often called a silent emergency, because it can be hard to see the damage it does to children around the world. In The First 1,000 Days, Roger Thurow makes readers sit up and take notice. He takes us to the four corners of the world--from the streets of Chicago to the villages of northern Uganda--to show how the right nutrition helps children not just survive, but thrive.Melinda Gates, former co-chair, Gates Foundation

-

“Powerful and important.”Nicholas Kristof, New York Times

-

“The stories are eye-opening... Here’s a reason to read the book: It’s actually full of hope.”Allison Aubrey, NPR correspondent, NPR.org

-

"[Roger Thurow] gives an intimate look at the struggles many women face...Poverty, lack of training, and prejudice are at the heart of the world's malnutrition problems...Thurow provides just enough grim facts on infant and mother mortality, the scarcity of food, sanitary conditions for birthing, and the general plight of impoverished families to garner sympathy without being melodramatic, and he also shows how women and children thrive under the right conditions. In today's global society, the children of the world need a voice. Thurow has spoken and made the issue clear: children everywhere need better food and water if they are going to grow into healthy adults."Kirkus Reviews

-

"A powerful and persuasive account."Publishers Weekly