By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

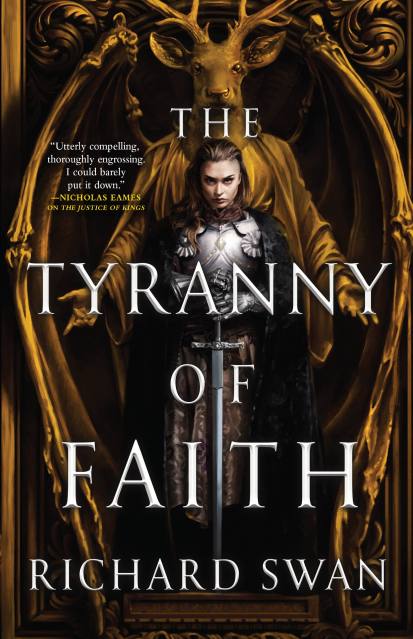

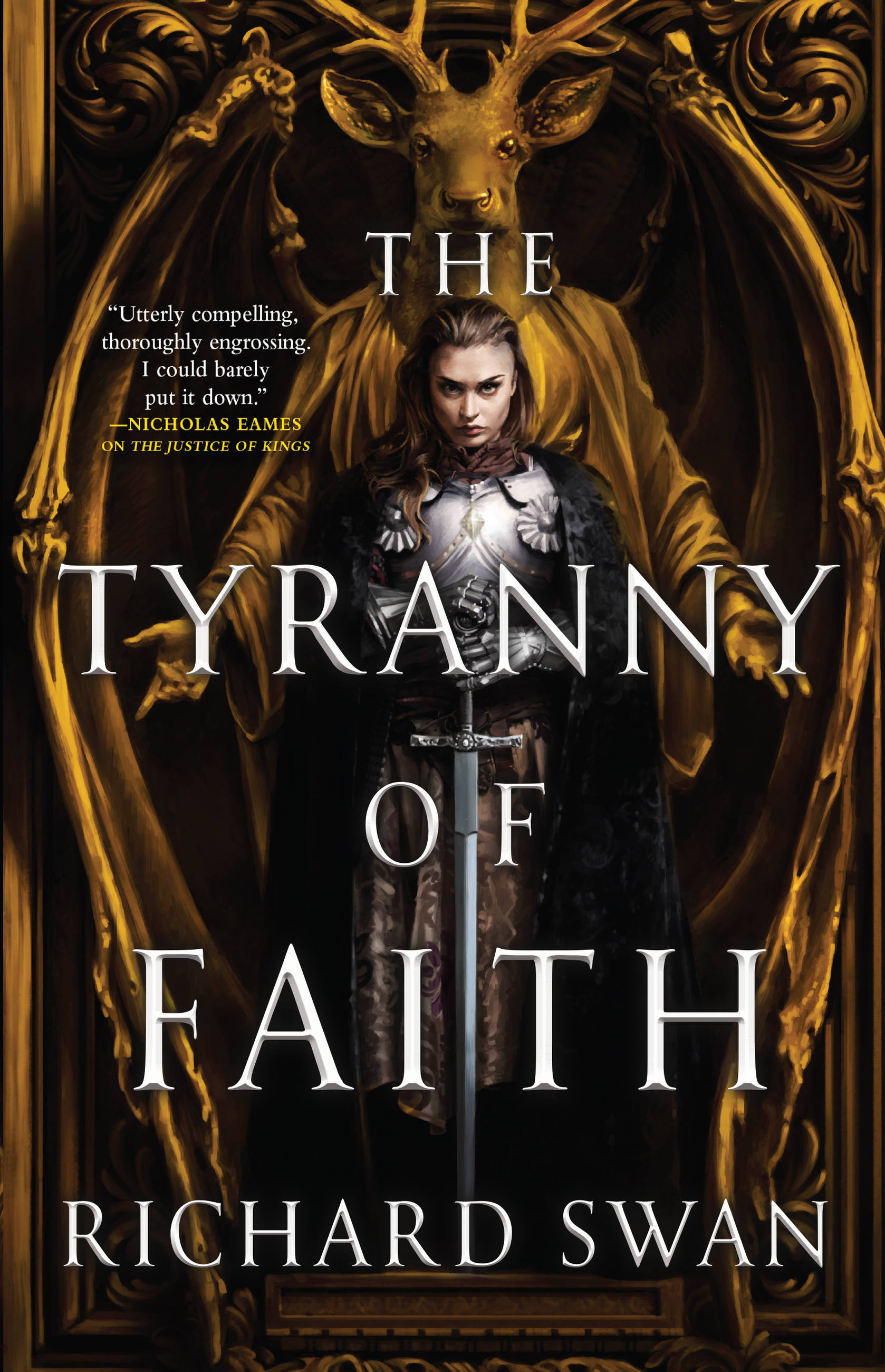

The Tyranny of Faith

Contributors

By Richard Swan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 8, 2023

- Page Count

- 592 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316361781

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 8, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Action, intrigue, and magic collide in the second book in an epic fantasy trilogy, where Sir Konrad Vonvalt’s role as an Emperor’s Justice requires him to be a detective, judge, and executioner all in one—but these are dangerous times to be a Justice . . .

A Justice’s work is never done.The Battle of Galen’s Vale is over, but the war for the Empire’s future has just begun. Concerned by rumors that the Magistratum’s authority is waning, Sir Konrad Vonvalt returns to Sova to find the capital city gripped by intrigue and whispers of rebellion. In the Senate, patricians speak openly against the Emperor, while fanatics preach holy vengeance on the streets.

Yet facing down these threats to the throne will have to wait, for the Emperor’s grandson has been kidnapped – and Vonvalt is charged with rescuing the missing prince. His quest will lead him – and his allies Helena, Bressinger and Sir Radomir – to the southern frontier, where they will once again face the puritanical fury of Bartholomew Claver and his templar knights – and a dark power far more terrifying than they could have imagined.

“Richard Swan’s sophisticated take on the fantasy genre will leave readers hungry for more.” – Sebastien de Castell on The Justice of Kings

“A fantastic debut.” – Peter McLean on The Justice of Kings

Also by Richard Swan:

The Empire of the Wolf

The Justice of Kings

The Tyranny of Faith

Series:

-

"Reminiscent of Andrzej Sapkowski ... [a] complex and dark historical fantasy series inspired by medieval state-military-church political conflicts."Kirkus (Starred Review) on The Tyranny of Faith

-

“With Swan’s impeccable worldbuilding, wit and claw-off-the-page characters, Tyranny of Faith seamlessly blends fantasy, mystery and horror into an addictive read, rife with unparalleled tension. A thoroughly satisfying sequel.”H. M. Long, author of Hall of Smoke, on The Tyranny of Faith

-

"A fantasy series that fans of authors like Joe Abercrombie, George R.R. Martin, or Sir Arthur Conan Doyle should have on their shelf ... The Tyranny of Faith is a compelling follow-up to Richard Swan’s The Justice of Kings, full of the intrigue, foreboding, detailed worldbuilding and deep character explorations that made the first book so good. I had high expectations going into this book and it surpassed them. A five star read, hands down.”Winter Is Coming on The Tyranny of Faith

-

"[Swan] has set the story up for a thrilling, heart-rending, dark, and tension-filled finale and I cannot wait to read it. Highest recommendation."SFFWorld on The Tyranny of Faith

-

“The Justice of Kings is equal parts heroic fantasy and murder mystery. Sir Konrad Vonvalt’s fierce intellect and arcane powers will make you long to follow in his footsteps, but it’s his young clerk, Helena who brings heart and dazzle to the story. Together they’re a formidable team, and Richard Swan’s sophisticated take on the fantasy genre will leave readers hungry for more.”Sebastien de Castell, author of Spellslinger, on The Justice of Kings

-

"A stunning piece of modern fantasy writing."RJ Barker, author of The Bone Ships, on The Justice of Kings

-

"The Justice of Kings is utterly compelling, thoroughly engrossing, and written with such skillful assurance I could barely put it down. The characters feel so real I swear I suffered every horror and hangover alongside them, and their world—though we see just the smallest portion of it here—feels vastly complex, poised on the brink of a disaster I can’t wait to watch unfold.”Nicholas Eames, author of Kings of the Wyld, on The Justice of Kings

-

“A fascinating look at justice, vengeance and the law — great characters, compelling and wonderfully written. A brilliant debut and fantastic start to the series.”James Islington, author of The Shadow of What Was Lost, on The Justice of Kings

-

"A marvelously detailed world with an engrossing adventure from a unique perspective."K. S. Villoso, author of The Wolf of Oren-Yaro, on The Justice of Kings

-

"A fantastic debut."Peter McLean, author of Priest of Bones, on The Justice of Kings

-

"Swan crafts a strong, dynamic character in Vonvalt . . . This promises good things from the series to come."Publishers Weekly on The Justice of Kings

-

“Murder mystery meets grimdark political fantasy in this first of a trilogy … An intriguingly dark deconstruction of a beloved mystery trope.”Kirkus (starred review) on The Justice of Kings

-

“The world of the Empire of the Wolf is a rich and interesting one … Readers will enjoy the world building, Sir Konrad and his crew, and the unique touches to a familiar fantasy tale.”Booklist on The Justice of Kings

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use