By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

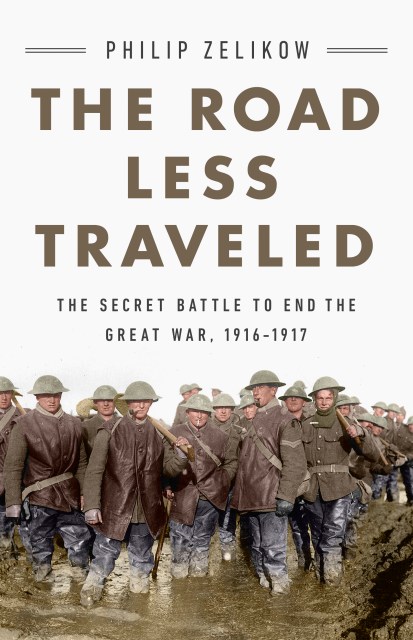

The Road Less Traveled

The Secret Battle to End the Great War, 1916-1917

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541750951

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Two years into the most terrible conflict the world had ever known, the warring powers faced a crisis. There were no good military options. Money, men, and supplies were running short on all sides. The German chancellor secretly sought President Woodrow Wilson’s mediation to end the war, just as British ministers and France’s president also concluded that the time was right. The Road Less Traveled describes how tantalizingly close these far-sighted statesmen came to ending the war, saving millions of lives, and avoiding the total war that dimmed hopes for a better world.

Theirs was a secret battle that is only now becoming fully understood, a story of civic courage, awful responsibility, and how some leaders rose to the occasion while others shrank from it or chased other ambitions. “Peace is on the floor waiting to be picked up!” pleaded the German ambassador to the United States. This book explains both the strategies and fumbles of people facing a great crossroads of history.

The Road Less Traveled reveals one of the last great mysteries of the Great War: that it simply never should have lasted so long or cost so much.

-

"Marvelous. What a well-wrought and haunting book this is. Philip Zelikow lucidly recounts and dissects how the worst consequences of the war of 1914-1918 almost came to be averted. He shows how leaders in both belligerent camps and the neutral United States strove mightily to end that conflict in 1916 and early 1917. This is a must-read book for understanding World War I and its consequences."John M. Cooper Jr, Emeritus Professor University of Wisconsin-Madison

-

"I read this book with unflagging interest, as my admiration for the carefulness of Zelikow’s research and the nuance of his argument grew virtually by the page. This is a gripping, granular analysis of one of modern history’s most fascinating and consequential might-have-beens, a must read for all practitioners and students of statecraft. "David M. Kennedy, Stanford University, Pulitzer and Bancroft Prize-winning author of Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War and Over Here: The First World War and American Society.

-

“Enthralling … a masterpiece … a page-turning narrative, based on meticulous archival scholarship yet a pleasure to read, the characters deftly drawn, the locations vividly realized. … This is an instant classic of diplomatic history.”Niall Ferguson for Times Literary Supplement

-

"The failure of Germany, Britain, and France halfway through World War I to reach a compromise peace mediated by Woodrow Wilson proved as disastrous for subsequent world history as the outbreak of the war itself. Philip Zelikow's enthralling narrative, with all the tautness of a mystery and based on thorough multinational research, unravels the earnest hopes, miscalculated tactics, and narrow political ambitions that all played a tragic role. Today's policy makers should ponder the lessons."Charles Maier, Leverett Saltonstall Professor of History, Harvard University

-

“In The Road Less Traveled, Zelikow brilliantly tells the diplomatic story of what he calls ‘the lost peace’ of August 1916–January 1917.”The New York Journal of Books

-

“[The Road Less Traveled] offers an engaging and detailed account of the secret peace negotiations among the warring nations …. Zelikow, chronicling the futility of these efforts with the keen eye of a former diplomat … does not shy away from attributing blame where he identifies missed or bungled opportunities in the past. But [the book] also speaks to the present.”Foreign Policy

-

“This fine and lucid scholarship has the additional benefit of the eye of an experienced practitioner.”Foreign Affairs

-

“(A) well-researched, well-written book... Focusing on the personalities and policies of the leaders of each of the Great Powers, Zelikow tells a gripping tale of the road not taken.”The Telegraph UK

-

“Despite the immense literature about World War I, there is, Zelikow attests, no history until now about this tragic impasse, making this supremely well-written work essential.”Booklist

-

“Zelikow shines fresh light on a major historical crossroads…. Outstanding revisionist history demonstrating what could have been a far more peaceful 20th century.”Kirkus (starred review)

-

“Deeply researched and scathingly critical of the war’s foremost political figures, this history offers an intriguing look at what might have been.”Publisher's Weekly

-

“Zelikow proves an effective storyteller with an easy, uncomplicated narrative that makes for good reading of solid, honest scholarship reminiscent sometimes of Barbara Tuschman’s The Guns of August.”New York Journal of Books

-

“Zelikow has written an important book. … The professor plays the part of a detective, constructing a well-written and well-argued account of a tragically missed opportunity.”The National Interest

-

“The history of the almost-peace of 1916-17 is complex, multilayered, and poorly understood. Drawing on a wealth of source material from the archives and documentary repositories of the warring powers, Zelikow has skillfully unearthed the dispiriting tale of overmatched officials, missed cues, foregone initiatives, personal biases, political gamesmanship, and the powerful momentum of war. In The Road Not Taken, Philip Zelikow has given us a riveting, sometimes maddening, and ultimately heartbreaking account of the Great War's greatest might-have-been.”Journal of Military History

-

“Through haunting depictions of forfeited opportunities, Zelikow reveals in his gripping history just how close several diplomats came to ending World War I two years before its resolution… With his rich archival study and ingenious recombination of documents, Zelikow relates a thorough, chronological tale of incompetence, missed signals, and misunderstandings in World War I.”Parameters, The US Army War College Quarterly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use