Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

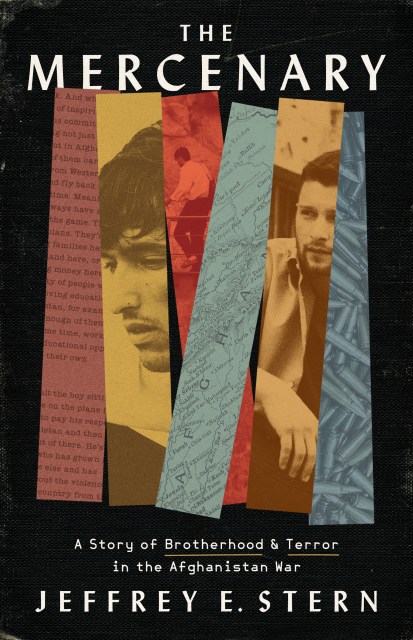

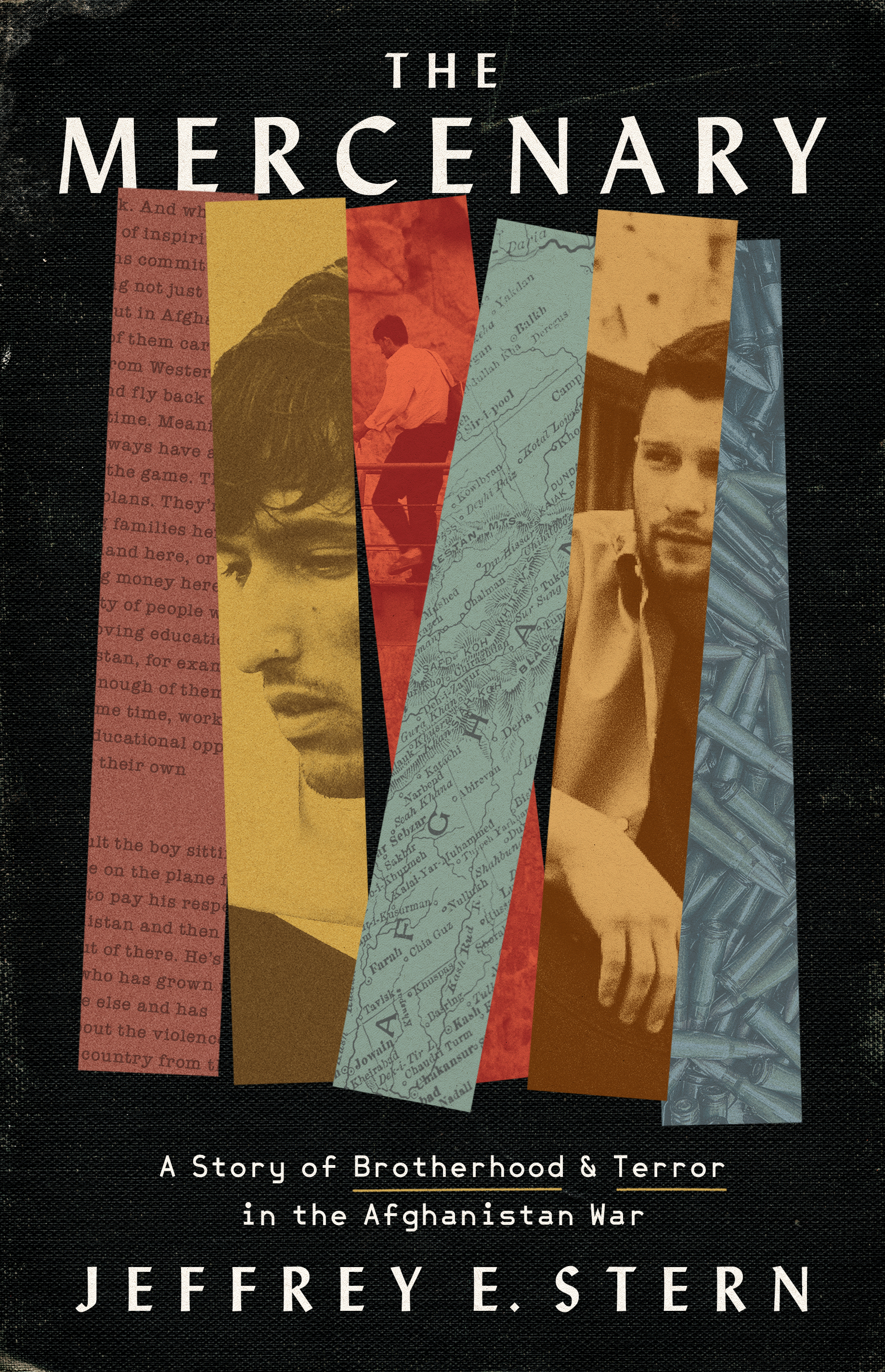

The Mercenary

A Story of Brotherhood and Terror in the Afghanistan War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 21, 2023

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541702455

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 21, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the early days of the Afghanistan war, Jeff Stern was scouring the streets of Kabul for a big story. He was accompanied by a driver, Aimal, who had ambitions of his own: to get rich off the sudden infusion of foreign attention and cash.

In this gripping adventure story, Stern writes of how he and Aimal navigated an environment full of guns and danger and opportunity, and how they forged a deep bond.

Then Stern got a call that changed everything. He discovered that Aimal had become an arms dealer, and was ultimately forced to flee the country to protect his family from his increasingly dangerous business partners.

Tragic, powerful, and layered, The Mercenary is more than a wartime drama. It is a Rashomon-like story about how politics and violence warp our humanity, and keep the most important truths hidden.

-

The Mercenary is one of the most important books about America’s longest war. It is a story of two individuals from two different continents brought together by war, and their courage, absolute commitment, and sacrifices for each other will make you laugh, cry, rage, break your heart, then make you laugh again and again until you are healed. It reads like an immersive thriller, but it is more compelling because the events are true and riveting. Mr. Stern has managed to show how the levers of power in Afghanistan devastate ordinary Afghans who try to make a living. The Mercenary is a must-read.Qais Akbar Omar, author of A Fort of Nine Towers

-

It’s remarkable how little we understand about what really went on in America’s twenty-year war in Afghanistan. The Mercenary is not just a story about that war—it’s a story about the misunderstanding that defined it. At once heart-pounding and complex, personal and expansive, this book is full of guns and dust and fast cars, but also something key to great war reporting: heart.Peter Bergen, CNN National Security Analyst

-

A moving story full of humanity and great curiosity. A riveting and heart-pounding war story. The Mercenary is a special book.Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, Oscar-winning directors of Free Solo

-

This is an extraordinary account of friendship between a journalist and his driver in wartime Afghanistan. Mr. Stern's brilliantly written and unvarnished portrayal of his debut as a bumbling wannabe war correspondent and close friendship with his driver, a man with a shrewd eye for opportunity, provides an important window into the spiral of corruption and violence perpetrated by the West’s war. A must read for those seeking a first hand view into the business of war in Afghanistan and those caught up in the madness.Jessica Donati, author of Eagle Down

-

“An affecting story of the human costs of a war.”Kirkus Reviews

-

"The Mercenary, by Jeffrey E. Stern, is ostensibly about a driver in Afghanistan, but again, it’s so beautifully told and riveting that it’s a page-turner even for people who don’t care about foreign policy. I haven’t stayed up reading this late in a long time."The Atlantic Daily Newsletter

-

"A gripping account of the terror and chaos of the Afghanistan war."Middle East Eye

-

"Stern’s account of a bond he developed with a cab driver during the early days of the U.S. war in Afghanistan, has accomplished a tremendous feat inasmuch as every paragraph aims to tell the truth."The Progressive Magazine