By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Looking to Get Lost

Adventures in Music and Writing

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2020

- Page Count

- 576 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316412629

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

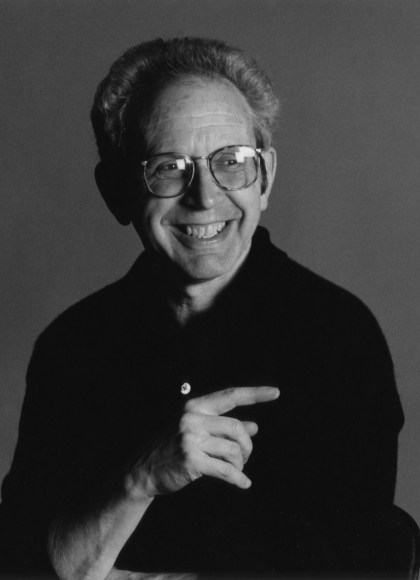

It covers old ground from new perspectives, offering deeply felt, masterful, and strikingly personal portraits of creative artists, both musicians and writers, at the height of their powers.

“You put the book down feeling that its sweep is vast, that you have read of giants who walked among us,” rock critic Lester Bangs wrote of Guralnick’s earlier work in words that could just as easily be applied to this new one. And yet, for all of the encomiums that Guralnick’s books have earned for their remarkable insights and depth of feeling, Looking to Get Lost is his most personal book yet. For readers who have grown up on Guralnick’s unique vision of the vast sweep of the American musical landscape, who have imbibed his loving and lively portraits and biographies of such titanic figures as Elvis Presley, Sam Cooke, and Sam Phillips, there are multiple surprises and delights here, carrying on and extending all the themes, fascinations, and passions of his groundbreaking earlier work.

One of NPR’s Best Books of 2020

One of Kirkus Review/Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020

One of No Depression’s Best Books of 2020

Genre:

-

"If there’s a leading figure among writers on American popular music—one who both defines and transcends the field—it has to be Peter Guralnick. . . . He approaches artists thoughtfully and connects with them—rather than their fame, beauty, or choice of handbag—and, through their voices, to their art. . . . For the author, it adds up to a study in the 'imaginative impulse.' For readers [this book] is an opportunity to appreciate Mr. Guralnick’s career, the music that has excited him, and the progress of his style."Preston Lauterbach, Wall Street Journal

-

"Be warned: the chapters on Solomon Burke, Doc Pomus, and Dick Curless just might squeeze tears out of you. . . . Willie Dixon, Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash, I imagine their spirits all around Guralnick, seeking what the author feels is the 'one common denominator for all great music, its capacity to bring a smile to your lips' … If this is what it means to get lost, it's a wonder anyone would ever care to be found."Brett Marie, Pop Matters

-

"Guralnick has always been particularly passionate about music that transcends categorization…. He seems to prize most of all the intuitive individuality that distinguishes artistry—what makes a Jerry Lee Lewis, a Ray Charles, or a Merle Haggard more than the sum of their influences. “Simply put,” the author writes at the beginning, “this is a book about creativity,” and the sort of creativity that he appreciates in others can be seen throughout his work as well. Some of the book’s richest pieces focus on performers who Guralnick feels haven’t been given their due or whose music has to be experienced live because it loses something in the studio [but he] is nearly as revelatory when writing about well-known musicians; he invites readers to appreciate Chuck Berry, Johnny Cash, and Ray Charles with fresh ears .…. A collection that clearly expresses the passion of musical discovery and lasting legacy."Kirkus Reviews (starred)

-

"Peter Guralnick is one of the 3 or 4 greatest writers in the country today. His searching intelligence, his unquenchable curiosity, his astonishing omnicompetence and his stunning scope of knowledge are all on display in this breathtaking volume dedicated to the odd duties of art and the taxing if transcendent assignments of genius. In Looking to Get Lost, Guralnick explores everything from the edifying enigma of blues icon Robert Johnson to the Appalachian absurdity of writer Lee Smith as he taps the veins of their, and other artists’, combustible originality — all while fashioning his own inimitable aesthetic and sublime style as a formidable master of American letters."Michael Eric Dyson, author of Long Time Coming: Reckoning with Race in America

-

"Peter Guralnick’s new book Looking to Get Lost: Adventures in Music and Writing is a slow read — slow because it’s impossible not to keep stopping and listening to music. After reading his essay on Skip James, I lost a solid two hours on Spotify. Many of the blues and country artists he covers in this collection— Robert Johnson, Ray Charles, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Howlin’ Wolf, Tammy Wynette, Chuck Berry — are huge figures, but because Guralnick is such a fine-grained storyteller and so driven by a deep passion for the music, even familiar characters emerge in a revealing new light."Hugo Lindgren, GQ

-

"Guralnick has established himself as the cultural historian who, when it comes to the roots of American rock ‘n’ roll, always takes the long view. . . . Looking to Get Lost features essays written from inside some of popular music’s longest shadows -- Ray Charles, Johnny Cash, Eric Clapton. But it also tells a subtle story of Guralnick’s own long journey."Boston Globe

-

"Peter Guralnick is a dedicated explorer, and like all explorers with true mastery of their quest, he is singular and tenacious. He goes deep into the difficult emotional undercurrents, and the contradictions of success, in the lives of artists, and by subtle extension, into his own life. He is a writer of great sensitivity and intuition, who lyrically untangles the network that exists between artist and art, persona and humanity, rhythm and melody, the mortal desires that underscore it all, and, crucially and seamlessly, his own relationship to everything and everyone he contemplates."Rosanne Cash

-

"Charlie Rich once wrote a beautiful song called “Feel Like Going Home.” It’s an extraordinary, yearning ballad. What is more remarkable, it was composed in response to a portrait of the singer written by Peter Guralnick, from an anthology with the same name. It is more common for music to inspire prose of various shades of purple, but this was a description of a man with conflicts at a moment after his greatest commercial success had left him, nonetheless, with crippling self-doubt and a tendency to self-destruct. Peter Guralnick’s portrait moved Charlie Rich with its honesty and humility, and he, in turn, was moved to render this lovely heartfelt song of longing. I can think of no finer compliment to a writer on the subject of music and humanity than to inspire a song in this way."Elvis Costello

-

"Peter Guralnick views his job as telling the Great American Story through the accomplishments of those who were larger than life and had the ability to make the nation feel as one through their music. What I love most about this anthology is Peter's Zip-Stripping of the synthetic veneer that cakes up on notable artists over time, masking the natural grain of their triumphs. He rebuilds the true legacy of these artists and personalities by slowly revealing the factors that made them tick and the creative impulses that drove them. [He] reminds us that exceptional rock writing is essentially sublime storytelling."Marc Myers, Jazzwax

-

"Peter Guralnick's Looking to Get Lost — a literary masterpiece — takes the reader on a fantastic journey through the very best of America's musical landscape. His jewel-like personal stories about Skip James, Bill Monroe, Doc Pomus, Solomon Burke, Joe Tex and others are priceless. Looking to Get Lost proves that nobody knows more about rhythm and blues, bluegrass, rockabilly, and soul music than Guralnick. This pulsing jukebox of a memoir and cultural history certifies that mighty claim."Douglas Brinkley, Author of Cronkite

-

"Others have studied and written about 20th-century American music with punch and flair, but nobody has done it like Peter Guralnick. [Here] as Guralnick writes about country singer Dick Curless, novelist Lee Smith, and bluesman Skip James, he also writes about himself. The result is a book that’s both reportage and memoir . . . A refreshing departure."Geoff Edgers, Washington Post

-

"In the introduction to this collection of profiles, American roots music chronicler Peter Guralnick plays that old game of imagining his favorite dinner party, composed of the subjects of his book. And what a gathering! Guralnick writes with deep empathy and respect about legends like Johnny Cash and Willie Dixon, lesser-known key figures like bluesman Lonnie Mack and music-adjacent kindred spirits like the novelist Lee Smith. This book will make you feel nostalgic for up-close conversations as Guralnick gently reaches the heart and soul of his subjects."Ann Powers, NPR Music

-

"In his new book, Guralnick has tracked down unlikely subjects….building human connections and bringing their worlds to life in novelistic detail. Looking to Get Lost is full of new insights on musical legends [as he] traces the personal experiences that led him to become a writer, and the creative revelations he discovered along the way. “Waylon Jennings, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland, Solomon Burke, Charlie Rich – all of them were passionately committed to finding a voice,” Guralnick says, [citing] in one moving passage a conversation with Ray Charles not long before he died, where the singer recalled singing a spiritual at Sam Cooke’s funeral 40 years earlier. “I gave my heart to it, man,” Charles said. “Everything that came out of me was truly genuine, there was nothing fake about it.”"Rolling Stone

-

"Guralnick’s dazzling new book of profiles is not a summation so much as a culmination of his remarkable work, which from the start has encompassed the full sweep of blues, gospel, country, and rock and roll. It covers old ground from new perspectives, offering deeply felt, masterful, and strikingly personal portraits of creative artists, both musicians and writers, at the height of their powers. Looking to Get Lost is such a treat, however, because it’s not only about music; the book gives us a glimpse at Guralnick the writer and Guralnick the reader and comes as close as we’re likely to get to something like an autobiography. What connects these pieces is Guralnick’s creativity, his love of getting lost in a story or a song, and his desire to write."Henry Carrigan, No Depression

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use