By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

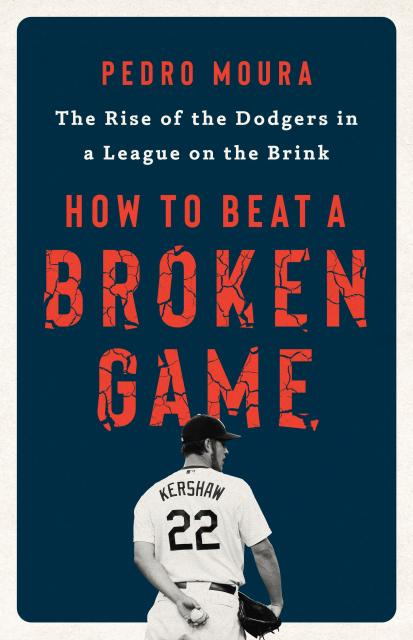

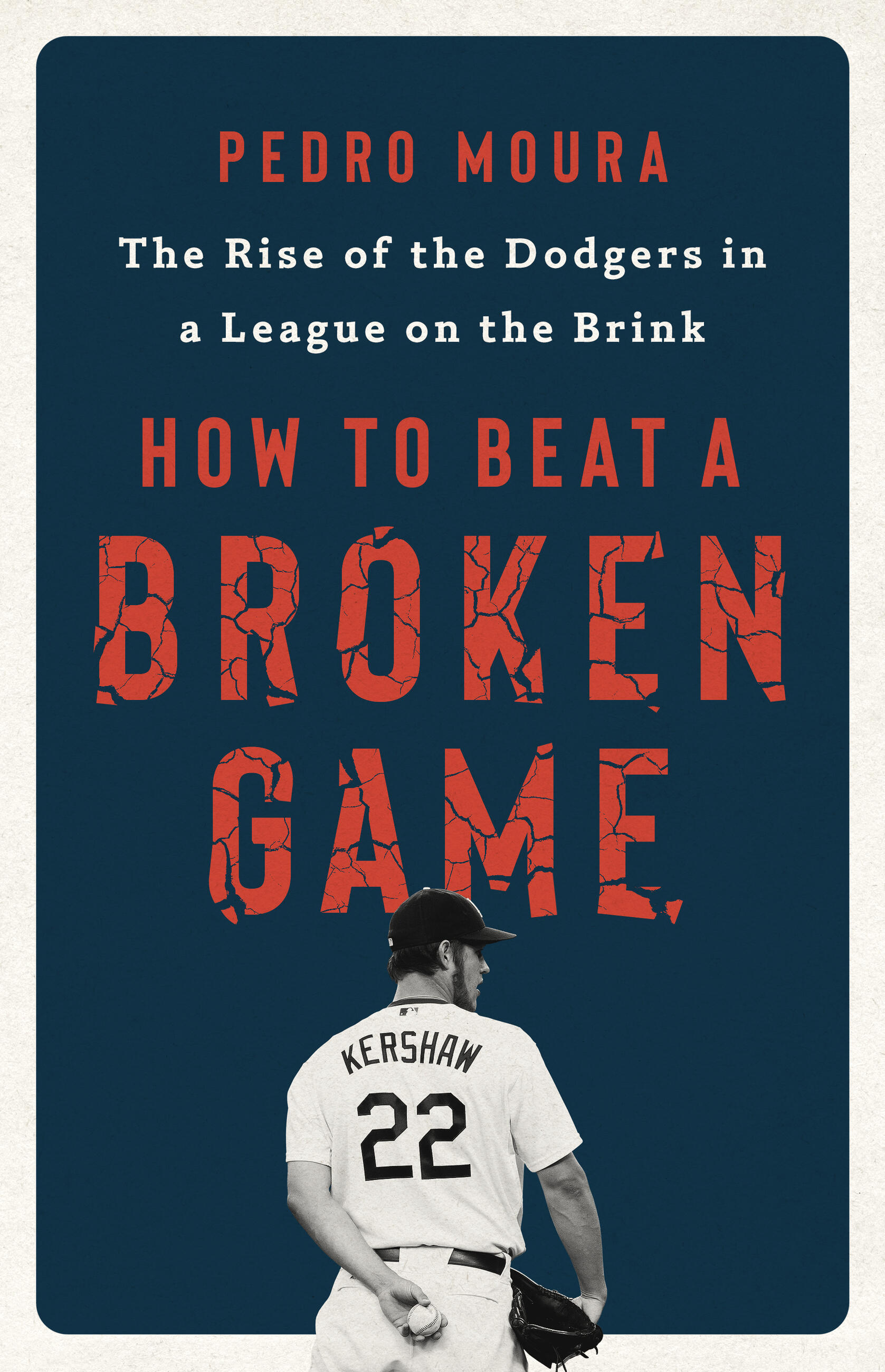

How to Beat a Broken Game

The Rise of the Dodgers in a League on the Brink

Contributors

By Pedro Moura

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 29, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541701434

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 29, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The inside story of how the Dodgers won their first championship in more than thirty years—but helped cripple the sport of baseball in the process

After years of frustrating playoff runs, the Los Angeles Dodgers finally reclaimed the World Series trophy after more than thirty years, led by star pitcher Clayton Kershaw, electric outfielder Mookie Betts, and a bevy of impressive young players assembled by team president Andrew Friedman. No team is better positioned to win now and in the future.

Yet winning at modern baseball is nothing like it was even twenty years ago. In the years since the famous Moneyball revolution, baseball has grown to look less like a sport than a Wall Street firm that traded its boiler room for a field. Teams relentlessly chase every tiny advantage to win games and make money, even as it hurts fans, TV ratings, and players, courting bigger problems in the long run.

This dramatic and insightful book takes you into the clubhouse with the championship players, as well as into the offices where teams constantly seek new ways to win—even when it hurts the game. How to Beat a Broken Game shows not only what it takes to win, but what it will take to save the sport.

-

“Today, baseball is deciding who it will serve in—and for—the coming generations. Soaked in greed and in the hands of Ivy League numbers crunchers, the game teeters between sport and thesis paper. Better it is in the hands of Pedro Moura, who, in How to Beat a Broken Game, has captured the science, the economics, and the soul of a pastime laboring to rediscover its most authentic self. It’s a brilliant book about the championship Dodgers. It’s a book about so much more.”Tim Brown, bestselling coauthor of The Phenomenon and Imperfect

-

“Pedro Moura has written a clear-eyed, absorbing account of the Dodgers’ rise—and baseball’s decline. It lays out everything broken about Major League Baseball while simultaneously reminding us exactly why we love the sport so much. How to Beat a Broken Game is a book with heart to match its brains. If only the league itself could say the same thing.”Eric Nusbaum, author of Stealing Home

-

“The scope of this book is just extraordinary. It’s supposedly about a single championship team, but it’s really about everything: technology and culture, insiders and outsiders, the young and the old, and all that’s right and wrong and now and next in the sport today. Moura is such a great reporter that he does what every writer wishes they could do: He comes to know even more about his subject than his sources do. I loved this book, even if it did make me feel old.”Sam Miller, bestselling coauthor of The Only Rule is It Has to Work

-

“Moura has written an insightful read for baseball fans who want to understand the inside workings of a remarkably successful franchise.”The National Review

-

“[S]pectacular.”Dodgers Way (Fansided)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use