Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

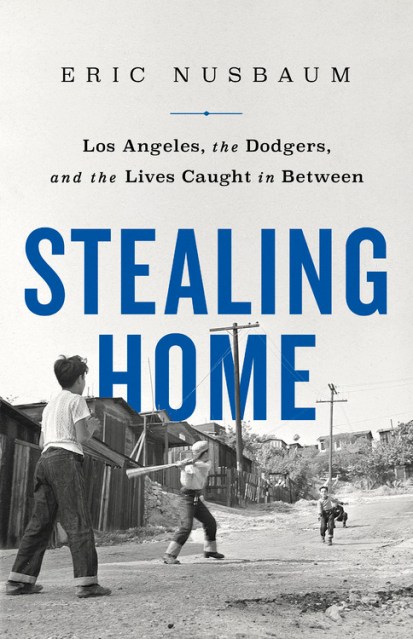

Stealing Home

Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between

Contributors

By Eric Nusbaum

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742222

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Dodger Stadium is an American icon. But the story of how it came to be goes far beyond baseball. The hills that cradle the stadium were once home to three vibrant Mexican American communities. In the early 1950s, those communities were condemned to make way for a utopian public housing project. Then, in a remarkable turn, public housing in the city was defeated amidst a Red Scare conspiracy.

Instead of getting their homes back, the remaining residents saw the city sell their land to Walter O’Malley, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Now LA would be getting a different sort of utopian fantasy — a glittering, ultra-modern stadium.

But before Dodger Stadium could be built, the city would have to face down the neighborhood’s families — including one, the Aréchigas, who refused to yield their home. The ensuing confrontation captivated the nation – and the divisive outcome still echoes through Los Angeles today.

-

“A scrupulously detailed account, written in novelistic, economical prose.”Los Angeles Times

-

“Nusbaum’s reporting and research are impressively deep, and his empathic writing brings his subjects to life. Stealing Home is a baseball book, but it's only glancingly about baseball. Really, it’s about how you can’t fight city hall, how one person’s American Dream often tramples another's and how myth‑making can be used to gloss over injustice and trauma.”People

-

“A well‑known tale of racial injustice given a fresh look... Provocative, essential reading.”Kirkus

-

“Eric Nusbaum takes several overlooked threads of history and weaves them into a vivid tapestry of twentieth‑century America that is at once sprawling and intimate, raw and poignant. Stealing Home is a relevant and important book‑‑and a fantastic read.”Margot Lee Shetterly, New York Times-bestselling author of Hidden Figures

-

“Stealing Home has a driving plot, a humane heart, and a proud conscience. Read it and enjoy the story, or read it and get mad, or read it and change your mind. Most importantly, read it.”Chuck D, founding member of Public Enemy

-

“In my family, the Dodgers caused pain and disillusionment when they left Brooklyn. But what happened in Los Angeles is a second drama with its own measure of financial manipulation, political intrigue, and working‑class heartache. Stealing Home takes on a whole new meaning in Eric Nusbaum’s marvelous book.”David Maraniss, New York Times-bestselling author of Path Lit by Lightning

-

“As a sports book, Stealing Home is astonishingly good‑but it’s more than just a sports book. The human experience it depicts resonates far beyond Los Angeles. The writing is lean, hard, and urgent. You’ll read it quickly and think about it for a long time.”Brian Phillips, New York Times-bestselling author of Impossible Owls

-

“A story perfectly told, riveting, moving, and deeply human.”Will Leitch, author of God Save the Fan

-

“A detailed, compelling history that goes well beyond Los Angeles. Eric Nusbaum asks an urgent modern question: What do the things we love actually cost? And who pays the price?”Jay Caspian Kang, writer-at-large, New York Times Magazine

-

“In Stealing Home, this visceral capsule on the working class originals of Palo Verde, Eric Nusbaum combines the scope of a historian, the diligence of an investigative reporter, and the grace and love‑of‑game of a seasoned sports writer. A rich and satisfying read from start‑to‑finish.”Daniel Hernandez, author of Down and Delirious in Mexico City

-

“Stealing Home is one of the best sports books I’ve ever read.”Dave Zirin, sports editor, The Nation