By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

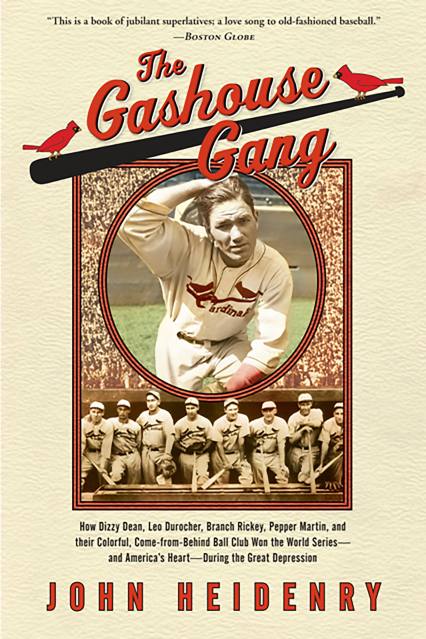

The Gashouse Gang

How Dizzy Dean, Leo Durocher, Branch Rickey, Pepper Martin, and Their Colorful, Come-from-Behind Ball Club Won the World Series-and America’s Heart-During the Great Depression

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 29, 2008

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586485689

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 29, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The year 1934 marked the lowest point of the Great Depression, when the U.S. went off the gold standard, banks collapsed by the score, and millions of Americans were out of work. Epic baseball feats offered welcome relief from the hardships of daily life. The Gashouse Gang, the brilliant culmination of a dream by its general manager, Branch Rickey, the first to envision a farm system that would acquire and “educate” young players in the art of baseball, was adored by the nation, who saw itself — scruffy, proud, and unbeatable — in the Gang.

Based on original research and told in entertaining narrative style, The Gashouse Gang brings a bygone era and a cast full of vivid personalities to life and unearths a treasure trove of baseball lore that will delight any fan of the great American pastime.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use