By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

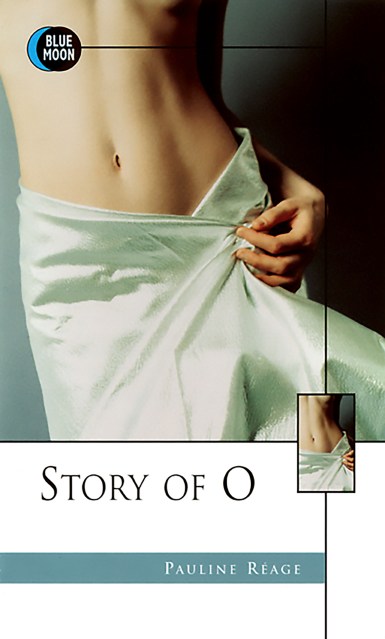

Story of O

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 8, 1998

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781562010355

Price

$13.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $13.99 $18.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 8, 1998. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

How far will a woman go to express her love? In this exquisite novel of passion and desire, the answer emerges through a daring exploration of the deepest bonds of sensual domination. “O” is a beautiful Parisian fashion photographer, determined to understand and prove her consuming devotion to her lover, René, through complete submission to his every whim, his every desire.

It is a journey of forbidden, dangerous choices that sweeps her through the secret gardens of the sexual underground. From the inner sanctum of a private club where willing women are schooled in the art of subjugation to the excruciating embraces of René’s friend Sir Stephen, O tests the outermost limits of pleasure. For as O discovers, true freedom lies in her pure and complete willingness to do anything for love.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use