Promotion

Use code BEST25 for 25% off storewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

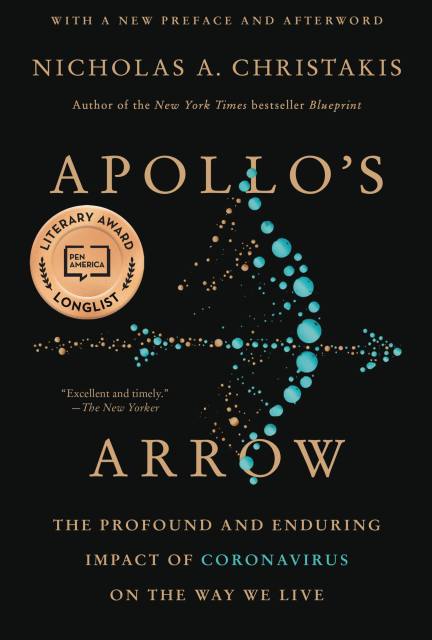

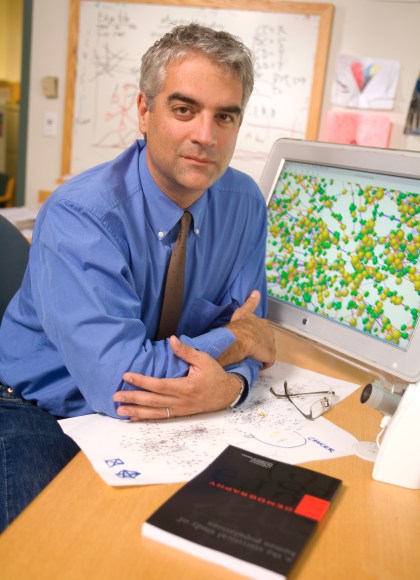

Apollo’s Arrow

The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 19, 2021

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316628204

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 19, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Apollo’s Arrow offers a riveting account of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic as it swept through American society in 2020, and of how the recovery will unfold in the coming years. Drawing on momentous (yet dimly remembered) historical epidemics, contemporary analyses, and cutting-edge research from a range of scientific disciplines, bestselling author, physician, sociologist, and public health expert Nicholas A. Christakis explores what it means to live in a time of plague—an experience that is paradoxically uncommon to the vast majority of humans who are alive, yet deeply fundamental to our species.

Unleashing new divisions in our society as well as opportunities for cooperation, this 21st-century pandemic has upended our lives in ways that will test, but not vanquish, our already frayed collective culture. Featuring new, provocative arguments and vivid examples ranging across medicine, history, sociology, epidemiology, data science, and genetics, Apollo’s Arrow envisions what happens when the great force of a deadly germ meets the enduring reality of our evolved social nature.

Genre:

-

“Seldom have we been gifted with a study of pandemic disease marked by such scope, wit, and erudition. Still rarer is one that appears while the rest of us scramble to make sense of a rapidly evolving crisis, one shaped by the very social forces that Nicholas Christakis has studied for decades. Apollo’s Arrow is more than history’s first draft. It will live on as a journal of the plague years, certainly, and it inspires as it instructs. Definitive, engaging, and astonishing. A tour-de-force.”Paul Farmer, Professor, Harvard Medical School, Founder, Partners in Health

-

“The world is ravenous for deep and accurate information about the most important event in the 21st century. No one is deeper than Nicholas Christakis, who ticks every box of expertise: medical, epidemiological, social, psychological, economic, historical. This is the place to go to understand the phenomenon that has turned the world, and our lives, upside down. Apollo’s Arrow is gripping, enlightening, and vitally important.”Steven Pinker, author of Enlightenment Now

-

"In this brilliant and timely book, scientist, scholar, physician, and writer Nicholas Christakis shines the light of history on our dark moment, and illuminates it as no one else can. Insightful, informative, and urgently necessary, Apollo's Arrow is this year's must-must-read."Daniel Gilbert, author of Stumbling on Happiness

-

“Rich in psychological, sociological, and epidemiological insights, only Nicholas Christakis could write a book this comprehensive and profound and even optimistic during our national calamity."Amy Cuddy, author of Presence

-

"Wow, what a feat this is — a fully developed book of extraordinary insight and superb narrative structure that was somehow written in the midst of a live-action recording of events. The journalist in me marvels. The failures Nicholas Christakis captures are so enormously discouraging, infuriating, and tragic. I can only imagine how long this book will be read for reasons beyond the obvious. I burned right through it and highly recommend it.”Michael Koryta, author of If She Wakes

-

"Apollo’s Arrow shoots straight and true to explain the scientific and social aspects of the coronavirus pandemic. Christakis’s background in biology, medicine, epidemiology, and sociology is a powerful formula for understanding this complex subject. I’m tempted to say that the gods created Christakis to write this book at this time. It is wise, vivid, and engaging."William D. Nordhaus, author of The Climate Casino, and 2018 Nobel Laureate in Economics

-

“To capture the COVID-19 pandemic requires unusually broad and deep scholarship, and an ability to integrate the too-often siloed domains of science, medicine, epidemiology, sociology, psychology, politics, and history, among other fields. In Apollo’s Arrow, Nicholas Christakis accomplishes this challenging task as few others could, with unusual clarity and an endless array of surprising insights; this book will no doubt become essential reading for a very wide audience. A tour-de-force.”Jeffrey Flier, MD, Former Dean of Harvard Medical School

-

"An instant history of an event that is by no means over. Exceptional. Magisterial."Niall Ferguson, Times Literary Supplement

-

“Gripping. An indelible portrait of a world transformed.”Hamilton Cain, Star-Tribune

-

“Authoritative...A welcome assessment of the reality of the epidemic that has changed our lives.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“An excellent overview of the pandemic thus far, this work will be of interest to those seeking a full explanation of how we got where we are in terms of the virus and the direction we might be going.”Library Journal

-

“Provocative…Astutely shows how pandemics are as much about our societies, values, and leaders as they are about pathogens.”Samuel V. Scarpino, Science

-

"Excellent and timely."The New Yorker

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use