Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

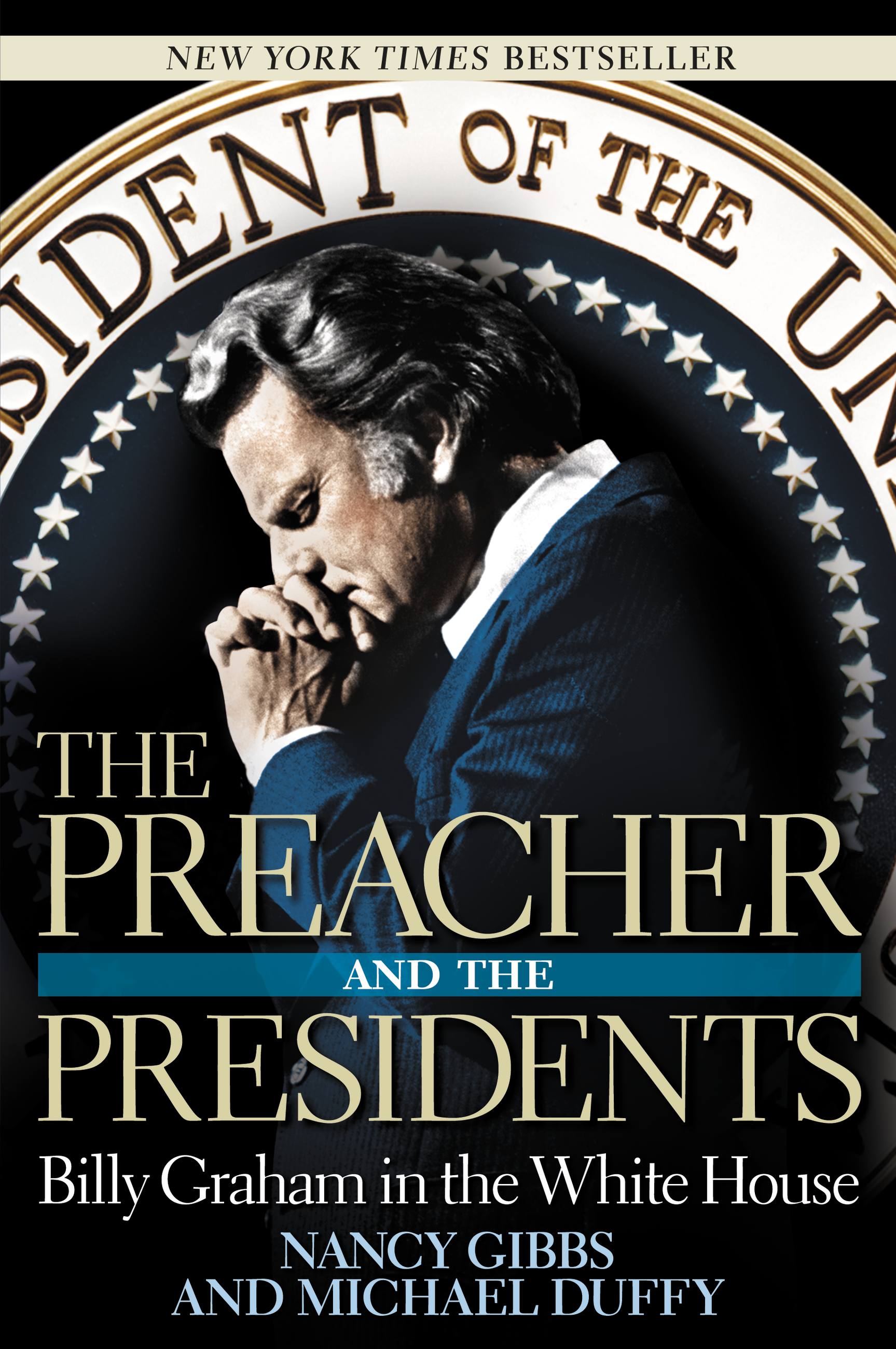

The Preacher and the Presidents

Billy Graham in the White House

Contributors

By Nancy Gibbs

By Michael Duffy

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 14, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

At a time when the nation is increasingly split over the place of religion in public life, The Preachers and the Presidents reveals how the world’s most powerful men and world’s most famous evangelist, Billy Graham, knit faith and politics together.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 14, 2007

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781599950389

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use