By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

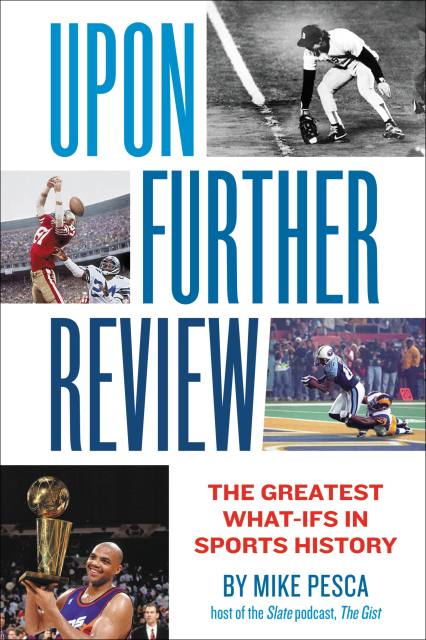

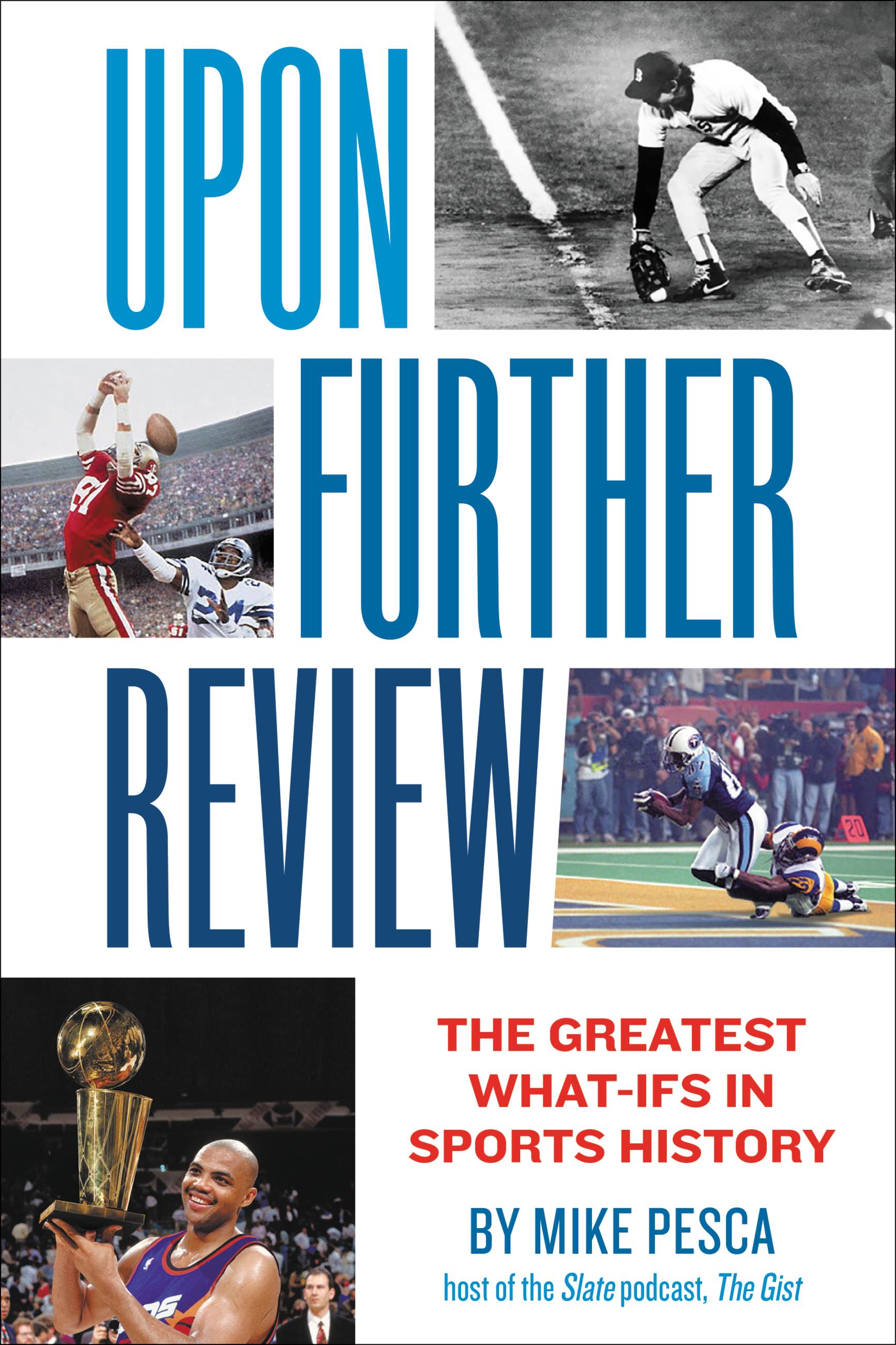

Upon Further Review

The Greatest What-Ifs in Sports History

Contributors

By Mike Pesca

Read by Mike Pesca

Read by Shira Springer

Read by Peter Thomas Fornatale

Read by Jesse Eisenberg

Read by Ben Lindbergh

Read by Jonathan Hock

Read by Mary Pilon

Read by Steve Kornacki

Read by Louisa Thomas

Read by Nate DiMeo

Read by Jeremy Schaap

Read by Neil Pain

Read by Will Leitch

Read by Julian E. Zelizer

Read by Liam Boylan-Pett

Read by Claude Johnson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 15, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478911845

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Intriguing…thought provoking…delightful.” –The Washington Post

No announcer ever proclaimed: “Up Rises Frazier!” “Havlicek commits the foul, trying to steal the ball!” or “The Giants Lose the Pennant, The Giants Lose The Pennant!” Such moments are indelibly etched upon the mind of every sports fan. Or rather, they would be, had they happened. Sports are notoriously games of inches, and when we conjure the thought of certain athletes – like Bill Buckner or Scott Norwood – we can’t help but apply a mental tape measure to the highlight reels of our minds. Players, coaches, and of course fans, obsess on the play when they ask, “What if?” Upon Further Review is the first book to answer that question.

Upon Further Review is a book of counterfactual sporting scenarios. In its pages the reader will find expertly reported histories, where one small event is flipped on its head, and the resulting ripples are carefully documented, the likes of…

What if the U.S. Boycotted Hitler’s Olympics?

What if Bobby Riggs beat Billie Jean King?

What if Bucky Dent popped out at the foot of the Green Monster?

What if Drew Bledsoe never got hurt?

Upon Further Review takes classic arguments conducted over pints in a pub and places them in the hands of dozens of writers, athletes, and historians. From turning points that every sports fan rues or celebrates, to the forgotten would-be inflection points that defined sports, Upon Further Review answers age old questions, and settles the score, even if the score bounced off the crossbar.

-

"What if you didn't read UPON FURTHER REVIEW? You'd miss a lot of mind-blowing fun. But why take the chance? Read it. You'll laugh. You'll learn. You'll impress your friends. There hasn't been a sure winner like this book since Mike Tyson beat Buster Douglas."Jonathan Eig, author of Ali: A Life and Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig

-

"The inevitable plight of sports fans is longing for what might have been. Retrospective analysis -- and wistful reimagining -- is what gets them through the night. UPON FURTHER REVIEW teems with such moonlit fantastical -- and a ravishing counterfactual revelation: sportswriters, the proud and embittered few, are actually a delightful bunch of goofball romantics."Nicholas Dawidoff, author of The Catcher Was A Spy and Collision Low Crossers.

-

"Enlightening and entertaining, Pesca's collection of hypothetical sports outcomes gives sports fans much food for thought."Publishers Weekly

-

"This is sports escapism brought to new and entertaining heights."Kirkus

-

"A thought-provoking venture into sports' road-not-taken possibilities."Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use