By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

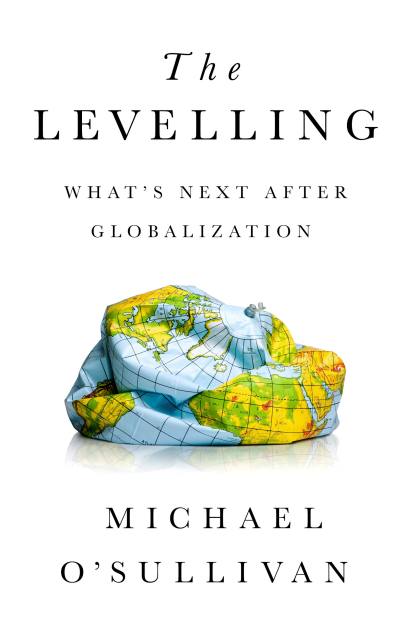

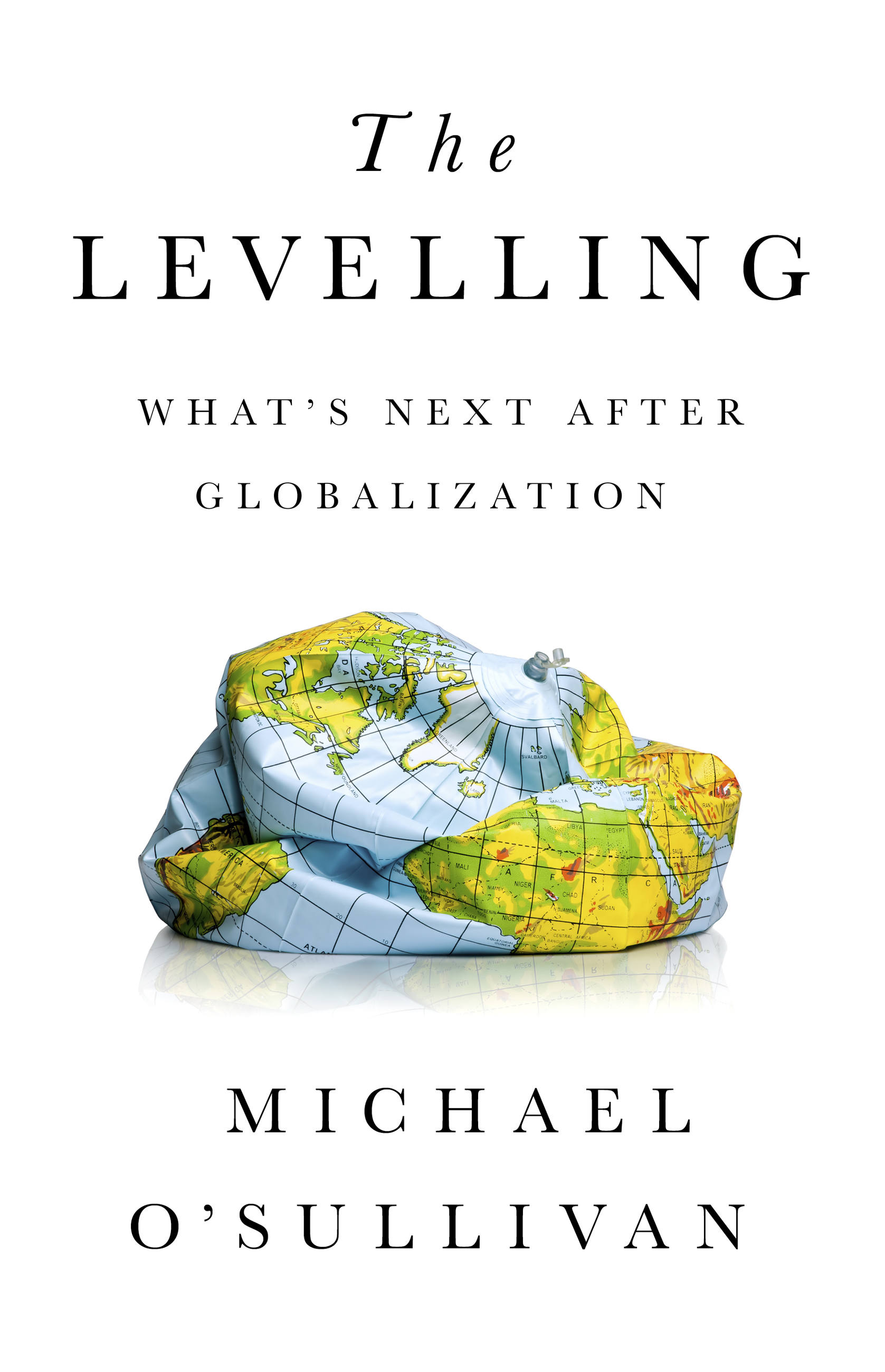

The Levelling

What's Next After Globalization

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 28, 2019

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541724082

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 28, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A brilliant analysis of the transition in world economics, finance, and power as the era of globalization ends and gives way to new power centers and institutions.

The world is at a turning point similar to the fall of communism. Then, many focused on the collapse itself, and failed to see that a bigger trend, globalization, was about to take hold. The benefits of globalization–through the freer flow of money, people, ideas, and trade–have been many. But rather than a world that is flat, what has emerged is one of jagged peaks and rough, deep valleys characterized by wealth inequality, indebtedness, political recession, and imbalances across the world’s economies.

The world is at a turning point similar to the fall of communism. Then, many focused on the collapse itself, and failed to see that a bigger trend, globalization, was about to take hold. The benefits of globalization–through the freer flow of money, people, ideas, and trade–have been many. But rather than a world that is flat, what has emerged is one of jagged peaks and rough, deep valleys characterized by wealth inequality, indebtedness, political recession, and imbalances across the world’s economies.

These peaks and valleys are undergoing what Michael O’Sullivan calls “the levelling”–a major transition in world economics, finance, and power. What’s next is a levelling-out of wealth between poor and rich countries, of power between nations and regions, of political accountability from elites to the people, and of institutional power away from central banks and defunct twentieth-century institutions such as the WTO and the IMF.

O’Sullivan then moves to ways we can develop new, pragmatic solutions to such critical problems as political discontent, stunted economic growth, the productive functioning of finance, and political-economic structures that serve broader needs.

The Levelling comes at a crucial time in the rise and fall of nations. It has special importance for the US as its place in the world undergoes radical change–the ebbing of influence, profound questions over its economic model, societal decay, and the turmoil of public life.

-

"Michael O'Sullivan chronicles a 'world turned upside down' in this fascinating new book detailing the twenty-first century's seismic shifts in technology, the global economy, and the balance of power. His call for a revival of democracies under siege in Britain, the US, and elsewhere is critical for the stable, productive, and peaceful world we all seek."Nicholas Burns, professor, Harvard University, and former US Under Secretary of State

-

"With a generous nod to the work of previous authors and experts, the author offers a solid synthesis of prognosis and practical solutions... the concept of O'Sullivan's Levelling presentation is fresh and thought-provoking."Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use