By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

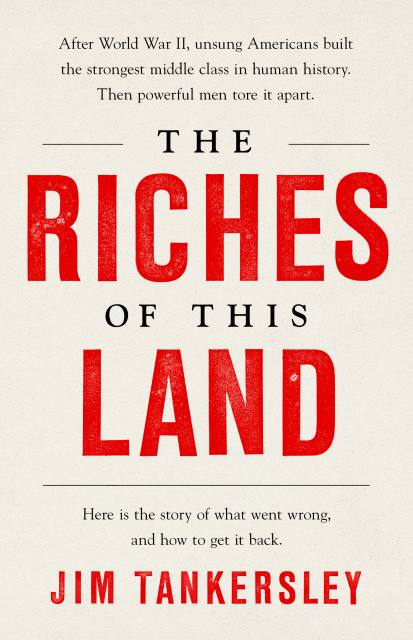

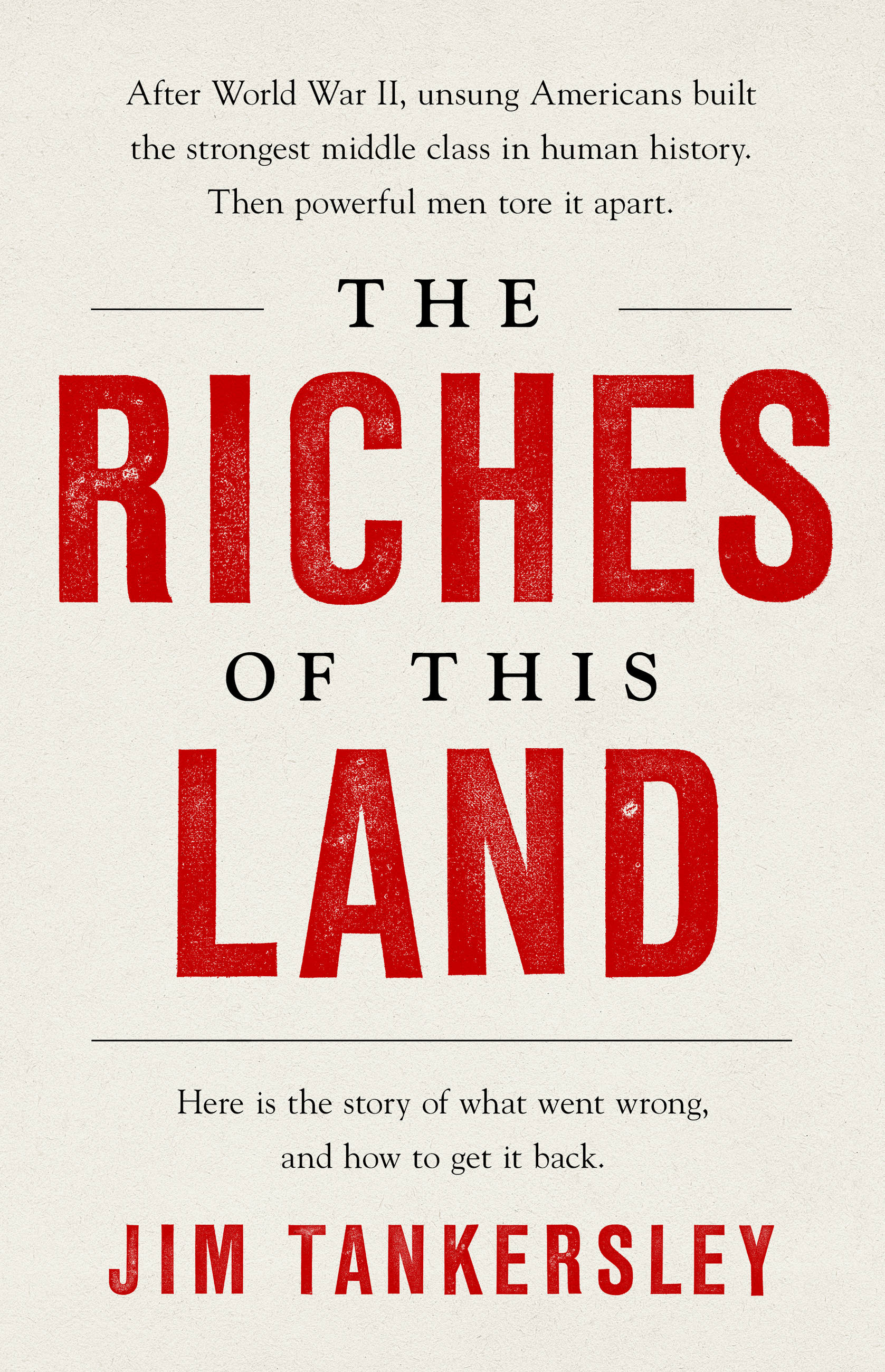

The Riches of This Land

The Untold, True Story of America's Middle Class

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 14, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541767850

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 14, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For over a decade, Jim Tankersley has been on a journey to understand what the hell happened to the world’s greatest middle-class success story — the post-World-War-II boom that faded into decades of stagnation and frustration for American workers. In The Riches of This Land, Tankersley fuses the story of forgotten Americans– struggling women and men who he met on his journey into the travails of the middle class– with important new economic and political research, providing fresh understanding how to create a more widespread prosperity. He begins by unraveling the real mystery of the American economy since the 1970s – not where did the jobs go, but why haven’t new and better ones been created to replace them.

His analysis begins with the revelation that women and minorities played a far more crucial role in building the post-war middle class than today’s politicians typically acknowledge, and policies that have done nothing to address the structural shifts of the American economy have enabled a privileged few to capture nearly all the benefits of America’s growing prosperity. Meanwhile, the “angry white men of Ohio” have been sold by Trump and his ilk a theory of the economy that is dangerously backward, one that pits them against immigrants, minorities, and women who should be their allies.

At the culmination of his journey, Tankersley lays out specific policy prescriptions and social undertakings that can begin moving the needle in the effort to make new and better jobs appear. By fostering an economy that opens new pathways for all workers to reach their full potential — men and women, immigrant or native-born, regardless of race — America can once again restore the upward flow of talent that can power growth and prosperity.

-

"Jim Tankersley lays out a compelling argument...Deftly weaving firsthand examples with accessible discussions of economic research."Washington Post

-

"But where Tankersley excels, as we face another its-the-economy-stupid election, is in parsing data on America's ailing middle class and leavening it with sympathetic portraits. As much as anything, he seeks to refute Trump's xenophobic, white-centered and misguided vision of how to make America great."Los Angeles Times

-

"Tankersley is a well-intentioned liberal who provides a telling--if sad, painful--account of the erosion of the post-WW II American Dream."New York Journal of Books

-

"Surprising and enlightening and timely. The Riches of This Land turns our understanding of why America once had an economy that delivered prosperity on its head. Only when black men, women of all races, and immigrants broke through blockades of oppression did their gains flow out to everyone. And, now, as Americans seek to find their way out from another devastating economic crisis, Tankersley exposes the true heroes of American prosperity - and why they are the source of our future renewal."Ibram X. Kendi, National Book Award-winning and #1 New York Times bestselling author

-

"The Riches of This Land is that rare combination of compassionate narrative and trenchant economic analysis to examine the often-misunderstood history of the American middle class and prescribe policies to revive it. Through great storytelling and a firm grasp on economics, Jim Tankersley gives us powerful insight on the key economic question of our time."David Wessel, director, Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution

-

"Globalization, the movement of manufacturing from America to China, and the current pandemic have shredded the American middle class. If we are to ever regain an economy that works for all people--not just a sliver of the economic elite--we need to understand who made America great in the first place. In his brilliantly written The Riches of this Land, Jim Tankersley tells the fascinating stories of the men and women who were the force behind the widespread prosperity we once enjoyed and who can lead us back to the promised land."Andy Stern, president emeritus, Service Employees International Union, and author of Raising the Floor

-

"A heartfelt, warm, and often moving book about working men and women and the troubles they face. It unites sharply observed stories with trenchant accounts of cutting-edge research to open up a conversation about systemic discrimination that could lay the foundation for an entirely new way of thinking about rebuilding both the working class and our economy."Rebecca Henderson, John and Natty McArthur University Professor, Harvard University, and author of Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

-

"An essential book from an essential reporter taking on the most pressing political question of our age. The Riches of This Land is a brilliant, searing, and human-centered examination of the American middle class, what it could be, and what it must be."Annie Lowrey, staff writer for the Atlantic and author of "Give People Money"

-

"The Riches of This Land is the inspiring story of the American economy's unsung heroes, and a manual for building a better future together as one nation."Arthur Brooks, professor of the practice of public leadership, Harvard Kennedy School, and author of Love Your Enemies

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use