By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

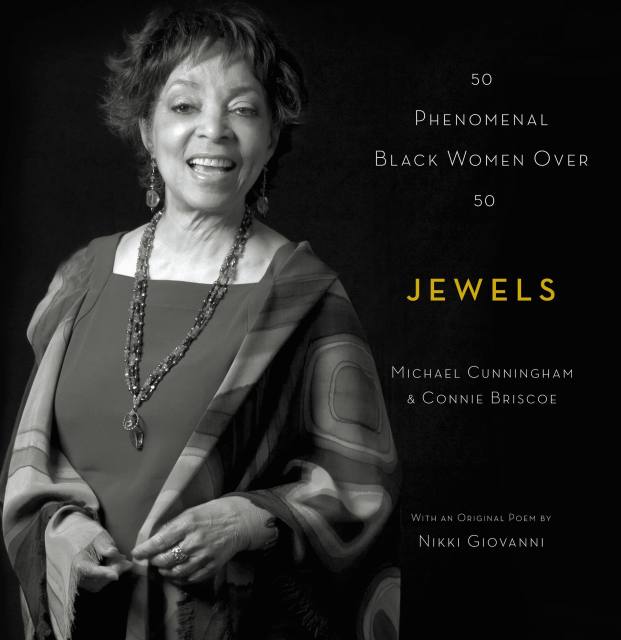

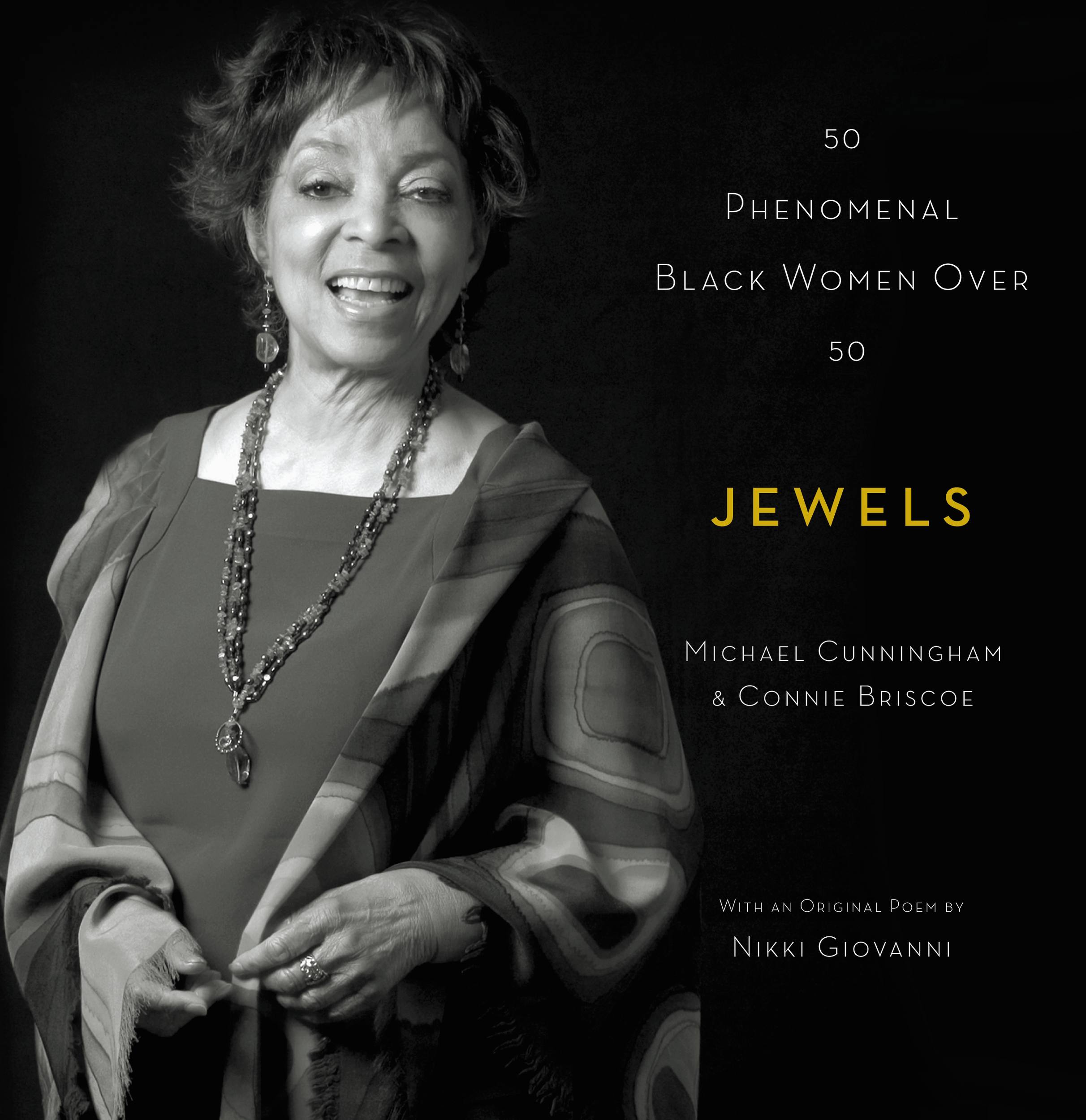

Jewels

50 Phenomenal Black Women Over 50

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 30, 2009

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316075701

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 30, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A photographer and a New York Times bestsellingnovelist profile 50 women over the age of 50 who have been remarkably successful — whether in reaching the top of thecorporate ladder, finding fame in politics or the arts, orraising a son to be proud of a single mother — and revealthe ways that they have prevailed despite daunting obstacles.

Jewels includes well-known and little-known womenalike, from teachers and executives to artists, authors, andentertainers. Among the celebrities profiled in the book areRuby Dee, Eleanor Holmes Norton, S. Epatha Merkerson,and Marion Wright Edelman. Coauthor Connie Briscoe alsoappears here as one of the featured Jewels, telling herinspiring personal story. World-renowned poet, writer,commentator, activist, and educator Nikki Giovannicontributes an original poem to the book.

Jewels includes well-known and little-known womenalike, from teachers and executives to artists, authors, andentertainers. Among the celebrities profiled in the book areRuby Dee, Eleanor Holmes Norton, S. Epatha Merkerson,and Marion Wright Edelman. Coauthor Connie Briscoe alsoappears here as one of the featured Jewels, telling herinspiring personal story. World-renowned poet, writer,commentator, activist, and educator Nikki Giovannicontributes an original poem to the book.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use