Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

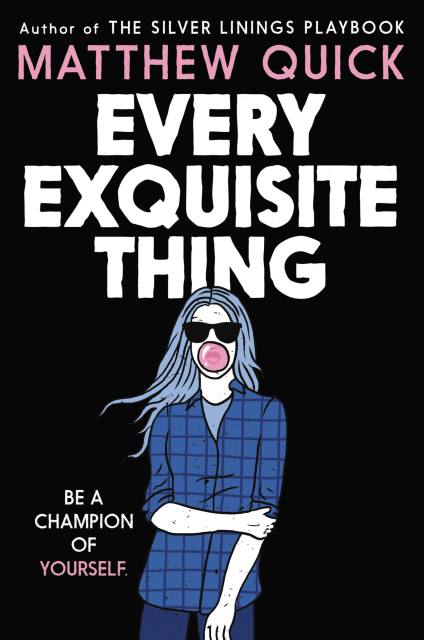

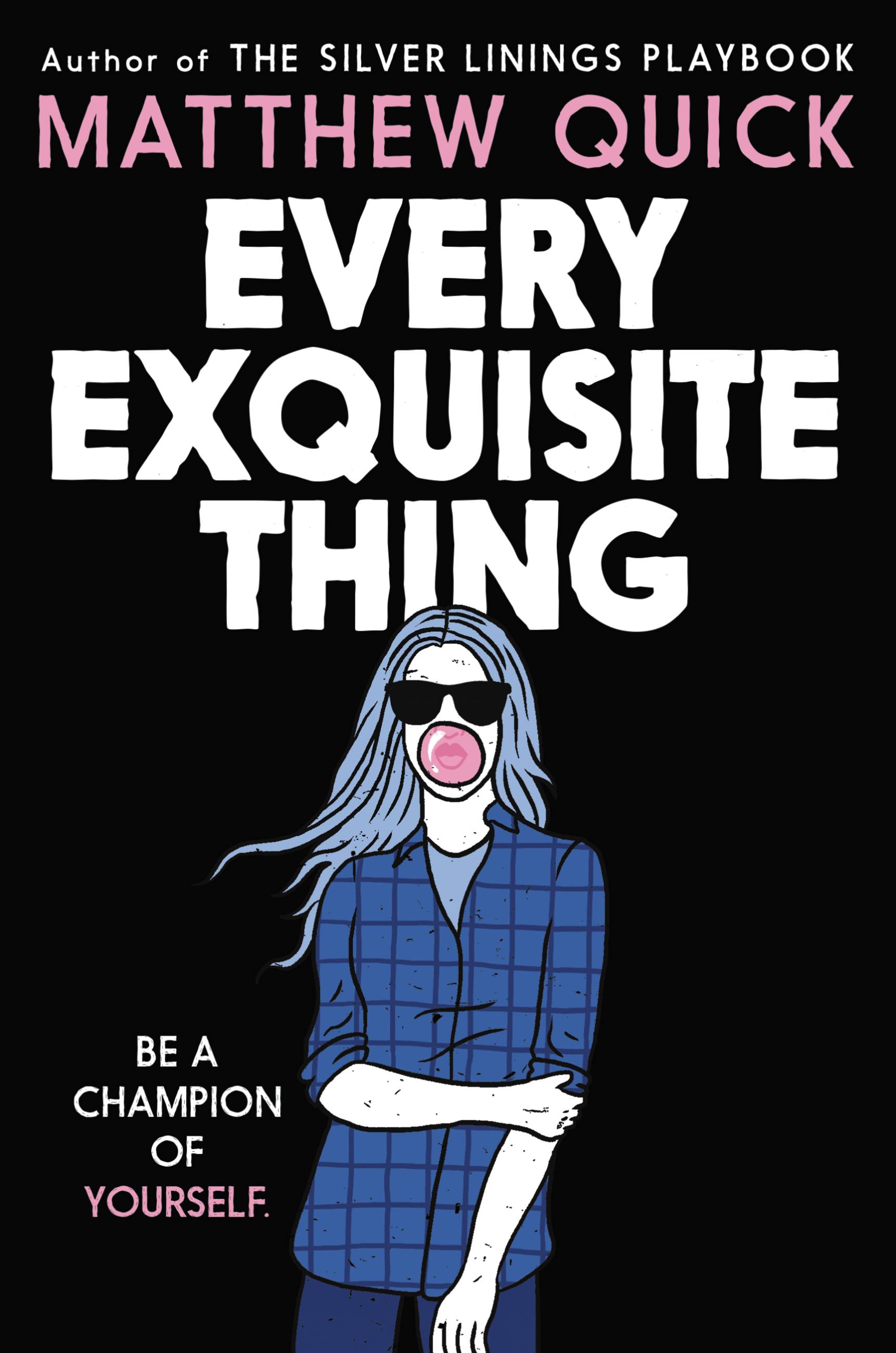

Every Exquisite Thing

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 31, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From the bestselling author of The Silver Linings Playbook comes a heartfelt and rebellious novel in the vein of The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

Nanette O'Hare is an unassuming teen who has played the role of dutiful daughter, hardworking student, and star athlete for as long as she can remember. But when a beloved teacher gives her his worn copy of The Bubblegum Reaper— a mysterious, out-of-print cult classic— the rebel within Nanette awakens.

As she befriends the reclusive author, falls in love with a young but troubled poet, and attempts to insert her true self into the world with wild abandon, Nanette learns the hard way that rebellion sometimes comes at a high price.

A celebration of the self and the formidable power of story, Every Exquisite Thing is Matthew Quick at his finest.

Nanette O'Hare is an unassuming teen who has played the role of dutiful daughter, hardworking student, and star athlete for as long as she can remember. But when a beloved teacher gives her his worn copy of The Bubblegum Reaper— a mysterious, out-of-print cult classic— the rebel within Nanette awakens.

As she befriends the reclusive author, falls in love with a young but troubled poet, and attempts to insert her true self into the world with wild abandon, Nanette learns the hard way that rebellion sometimes comes at a high price.

A celebration of the self and the formidable power of story, Every Exquisite Thing is Matthew Quick at his finest.

Genre:

-

"Every Exquisite Thing lives up to the hype...You're going to wish you could follow Quick's awesome heroine Nanette for another 500 pages or so when you get to the end."Bustle.com

-

* "The author's beautifully written first-person narrative captures the thoughts and feelings of a sensitive eighteen-year-old girl struggling against the shallowness she sees around her....All of the elements of this novel work together to make this an outstanding coming-of-age story."VOYA, starred review

-

* "Quick continues to excel at writing thought-provoking stories about nonconformity.... [and] paints a compelling portrait of a sympathetic teenager going through the trial-and-error process of growing up."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

* "Like the many anticonformity books before it, this will find a dedicated audience among teen readers."School Library Journal, starred review

-

"Quick's story will speak to teenage eccentrics: loners, rebels, and creative types; the kind to follow Booker's suggestions to read Bukowski and Neruda; those ripe for transformation."Horn Book

-

"A strong, well-written female protagonist sets this coming-of-age novel apart."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Quick creates beautifully well-rounded characters, particularly Nanette, whose first-person narrative, rich with wry observations and a kaleidoscope of meaningful emotions, offers great insight into the mind of a teen on a sometimes sluggish, spiraling path toward sorting herself out."Booklist

-

"[Quick] will give readers lots to chew on as they join Nanette in sorting out angst from general privileged malaise."The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

- On Sale

- May 31, 2016

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316379588

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use