By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

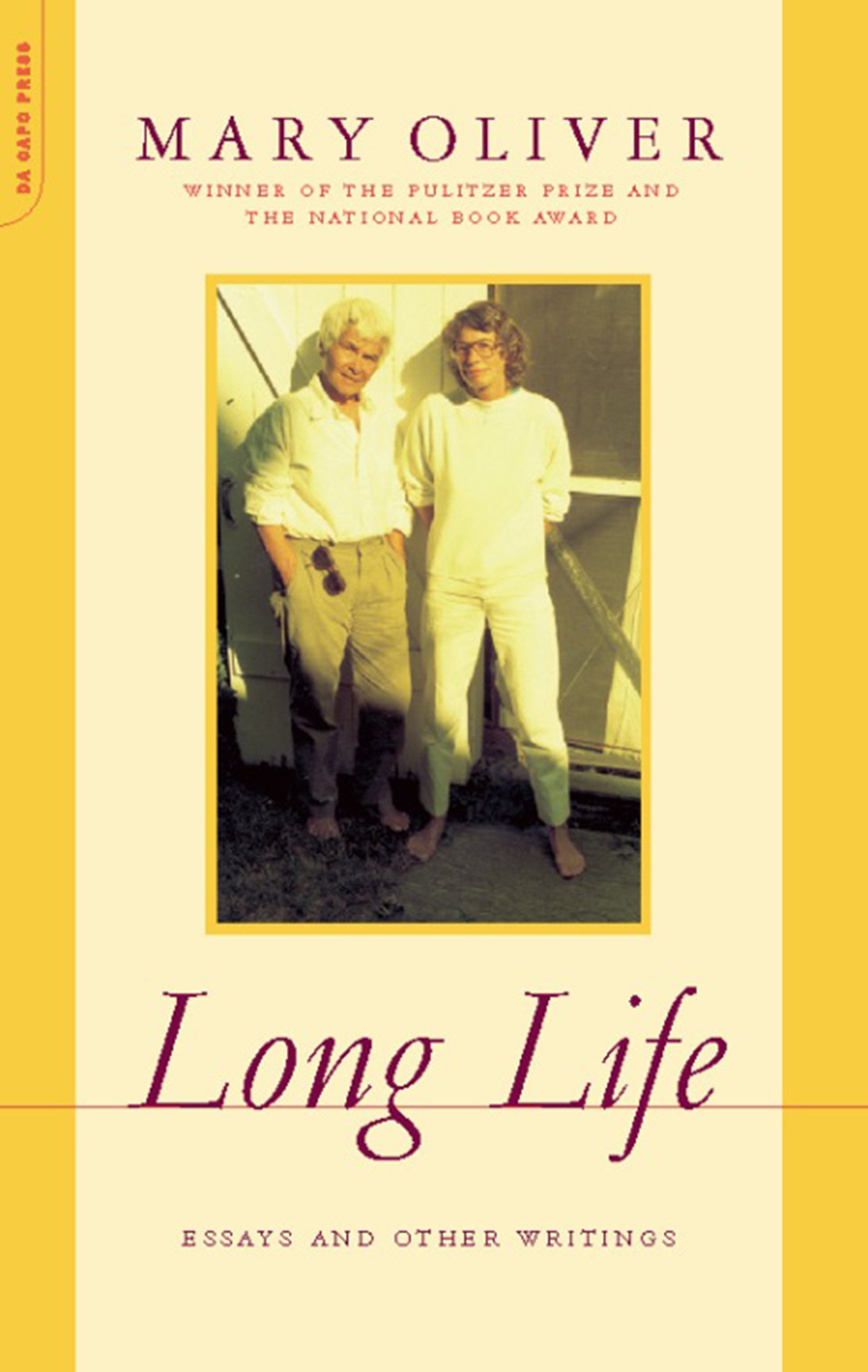

Long Life

Essays and Other Writings

Contributors

By Mary Oliver

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 2, 2005

- Page Count

- 120 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780786739486

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 2, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

With the grace and precision that are the hallmarks of her work, Oliver shows us how writing "is a way of offering praise to the world" and suggests we see her poems as "little alleluias." Whether describing a goosefish stranded at low tide, the feeling of being baptized by the mist from a whale's blowhole, or the "connection between soul and landscape," Oliver invites readers to find themselves and their experiences at the center of her world. In Long Life she also speaks of poets and writers: Wordsworth's "whirlwind" of "beauty and strangeness"; Hawthorne's "sweet-tempered" side; and Emerson's belief that "a man's inclination, once awakened to it, would be to turn all the heavy sails of his life to a moral purpose."

With consummate craftsmanship, Mary Oliver has created a breathtaking volume sure to add to her reputation as "one of our very best poets" (New York Times Book Review ).

Genre:

-

"A rigorous mind combined with a capacity for devotion; a desire to find the exact, economical, shining phrase; a wish to witness, and a wish to share."Chicago Tribune

-

"Oliver writes exquisitely lucid prose. Here, in her most generously personal essays to date, she articulates the beliefs, observations, and inspirations that feed her poetry. Essential...radiant."Booklist

-

Praise for Mary Oliver

-

"A master of spare and evocative imagery."Poetry

-

"What good company Mary Oliver is!"Los Angeles Times

-

"A great poet....She is amazed but not blinded."Boston Globe

-

"The gift of Oliver's poetry is that she communicates the beauty she finds in the world and makes is unforgettable."Miami Herald

-

"Oliver's poems are thoroughly convincing as genuine, moving, and implausible as the first caressing breeze of spring."The New York Times

-

"Oliver might be accused of an untransformed and reactionary romanticism. One would think that poems about self, nature, death, and ecstasy had run their course in English. Think again."Chicago Tribune

-

"Who wouldn't want to be part of Mary Oliver's world?"Appalachian Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use