By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

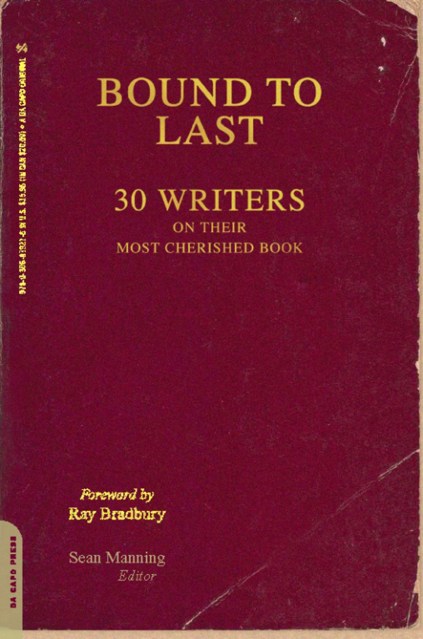

Bound to Last

30 Writers on Their Most Cherished Book

Contributors

By Sean Manning

Foreword by Ray Bradbury

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 26, 2010

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306819391

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 26, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Bound to Last,an amazing array of authors comes to the passionate defense of the printed book with spirited, never-before-published essays celebrating the hardcover or paperback they hold most dear — not necessarily because of its contents, but because of its significance as a one-of-a-kind, irreplaceable object. Whether focusing on the circumstances behind how a particular book was acquired, or how it has become forever “bound up” with a specific person, time, or place, each piece collected here confirms–poignantly, delightfully, irrefutably–that every book tells a story far beyond the one found within its pages.

In addition to a foreword by Ray Bradbury, Bound to Last features original contributions by:

Chris Abani, Rabih Alameddine, Anthony Doerr, Louis Ferrante, Nick Flynn, Karen Joy Fowler, Julia Glass, Karen Green, David Hajdu, Terrence Holt, Jim Knipfel, Shahriar Mandanipour, Sarah Manguso, Sean Manning, Joyce Maynard, Philipp Meyer, Jonathan Miles, Sigrid Nunez, Ed Park, Victoria Patterson, Francine Prose, Michael Ruhlman, Elissa Schappell, Christine Schutt, Jim Shepard, Susan Straight, J. Courtney Sullivan, Anthony Swofford, Danielle Trussoni, and Xu Xiaobin

Genre:

-

Montreal Gazette (Canada), 1/15/11

“As nostalgic as it is hopeful.”

Wall Street Journal, 2/13/11

“The pairings of book and writer are sometimes unexpected.”

Bookslut, February 2011

“Readers hear from writers across the literary spectrum on titles that range from a Dungeons and Dragons manual to The Bible…Every page leads the reader into another intimate moment, into funny reminiscences, heartfelt recollections and more touching tributes…Whether you embrace the notion of hard copy over e-book or not, this is a book for the reader. It is a collection of extremely well-written personal essays by very smart people who love books. It celebrates the act of reading, the impact books can have on our lives and the long reach that words carry.”

The Writer, March 2011

“Reading these essays, you can't help but think of your favorite books, who gave them to you, and what was happening in your life when you read them…The essays here can move you to tears and laughter while giving you ideas for books to add to your collection.”

WTVF TV (CBS, Nashville), 1/11/11

“Is reading more part of your resolutions for 2011? This is the perfect book to help you with your selections. A great source to keep always.”

-

New City, 11/4/10

“Not only do many of these essays go to the soul of how their writers found their calling, but the diversity of their experiences is totally unexpected…Refreshingly, this collection poignantly delivers even more than it promises.”

Milwaukee Shepherd Express, 11/5/10

“Most of the essayists gathered in this slender volume are of younger generations and speak of particular books as memory chests—not just the words themselves but the tactile nature of books, their dog-eared covers, creased pages and underlined sentences.”

San Francisco Book Review, 11/1/10

“A book lover's book. If one ever suspected that books change people's lives, the essays in this collection confirm that…Whether one's taste is traditional or postmodern, a book lover will most likely love this collection.”

Bookforum.com's “Paper Trail” Blog, 11/11/10

“There are some excellent and in some cases deeply inspired entries.”

St. Petersburg Times, 11/14/10

“Intriguing essays from a wide range of writers about beloved books and the personal reasons they are valued.”

-

Shelf Unbound, December 2010

“[A] deftly diverse and surprising anthology…serving both as a compelling reminder of how books have changed our own lives and as an impetus to pick up a dusty volume that transformed someone else's.”

Maclean's (Canada), 11/24/10

“A surprising gem…We aren't simply given an appreciation of the selected titles. We also get a sense of the magic dust that floats around a given book: its smell; the painful or happy personal memories attached to it; where it was purchased, found or given; the palpable comfort gained from the mere presence of a worn, tattered copy sitting on a desk.”

Tucson Citizen, 12/15/10

“Each piece reaffirms that every book tells a story in addition to the one found between its covers…This is a wonderful little book. The foreword by Ray Bradbury sets just the right tone.”

Parade, 12/19/10

“Harold Robbins' once-racy The Carpetbaggers is one of several unexpected picks in this collection, which also touts classic fare like James Joyce's Ulysses. And since each sparkling essay (by writers including Julia Glass and Francine Prose) is really a mini-memoir, it can be savored on at least two levels.”

-

USA Today's “Pop Candy” blog, 10/29/10

“I can also recommend Bound to Last…in which famous authors talk lovingly about Ulysses, Invisible Man, Naked Lunch, The Crying of Lot 49 and so many more terrific titles. It just makes me want to crawl in bed and read right now.”

PopMatters.com, 11/1/10

“One of the real strengths of the volume is its eclecticism: contributors range from well-established authors (Ray Bradbury contributed the introduction) to relative novices…The variety of perspectives, and books selected to write about, is impressive…All in all, Bound to Last is a timely reminder of the permanent importance of printed books.”

Bookviews.com, November 2010

“[A] testimony to the pleasures of having a favorite book at hand to re-read and re-visit…For bibliophiles it will provide some delightful reading.”

NBCNewYork.com, 11/3/10

“Now that devices like the Kindle are making the printed word seem even more like an inevitably doomed dinosaur, there's never been a better time for a loving valentine to the book.”

-

Elle, November 2010

“Presents a tantalizing array of essays on beloved books.”

Instinct, November 2010

“These stories serve as love letters to the printed page. With Kindles and iPads threatening the future of old-fashioned books, the timing for Bound couldn't be better.”

New York Journal of Books, 10/26/10

“Bound to Last is the perfect book for a lover of books. It's a work that will be cherished by those who enjoy not only the words of writers, but also the books from which they come. Each essay is well crafted and written with feeling as the writers share their personal connections to a special book in their life. Bound to Last will also be treasured not just as a collection of essays, but as a recommendation source itself, as each essay will leave readers wanting to read the book discussed. At a time where so many are neglecting the art that is the book, it's wonderful to have 30 books that remind us that there is nothing like the real thing.”

Corduroy Books, 10/26/10

“This book's made for all of us who [love books].”

-

InfoDad.com, 11/18/10

“A wonderful gift for a more literary friend…What joy this little book includes for those who love today's authors!... not only provides insight into 30 of today's writers but also can make the recipient of this gift look at the books the writers choose as their favorites in a new light.”

Time Out Chicago, 11/18/10

“The perfect gift for a writer, a reader, or someone looking for that next great book.”

Minneapolis Star Tribune, 11/20/10

“This book is steeped in the sentiment of true book lovers.”

Bookgasm.com, 11/29/10

“It's an admirable venture. The foreword by Ray Bradbury plants you in the perfect mood for the contributors to follow.”

TheBookWeb.com, 11/21/10

“A paean to the printed book at a moment when sales of e-books are climbing and everyone seems to be reading digital editions on their Kindles and Nooks and Ipads…Bound to Last is a welcome and timely reminder that a printed book…can command an importance and an intense affection that transcends its contents.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use