Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

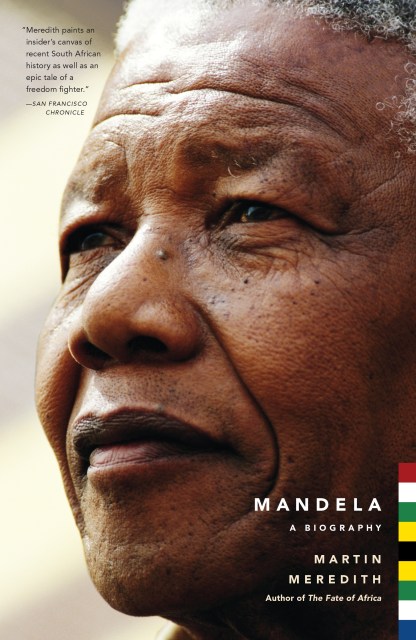

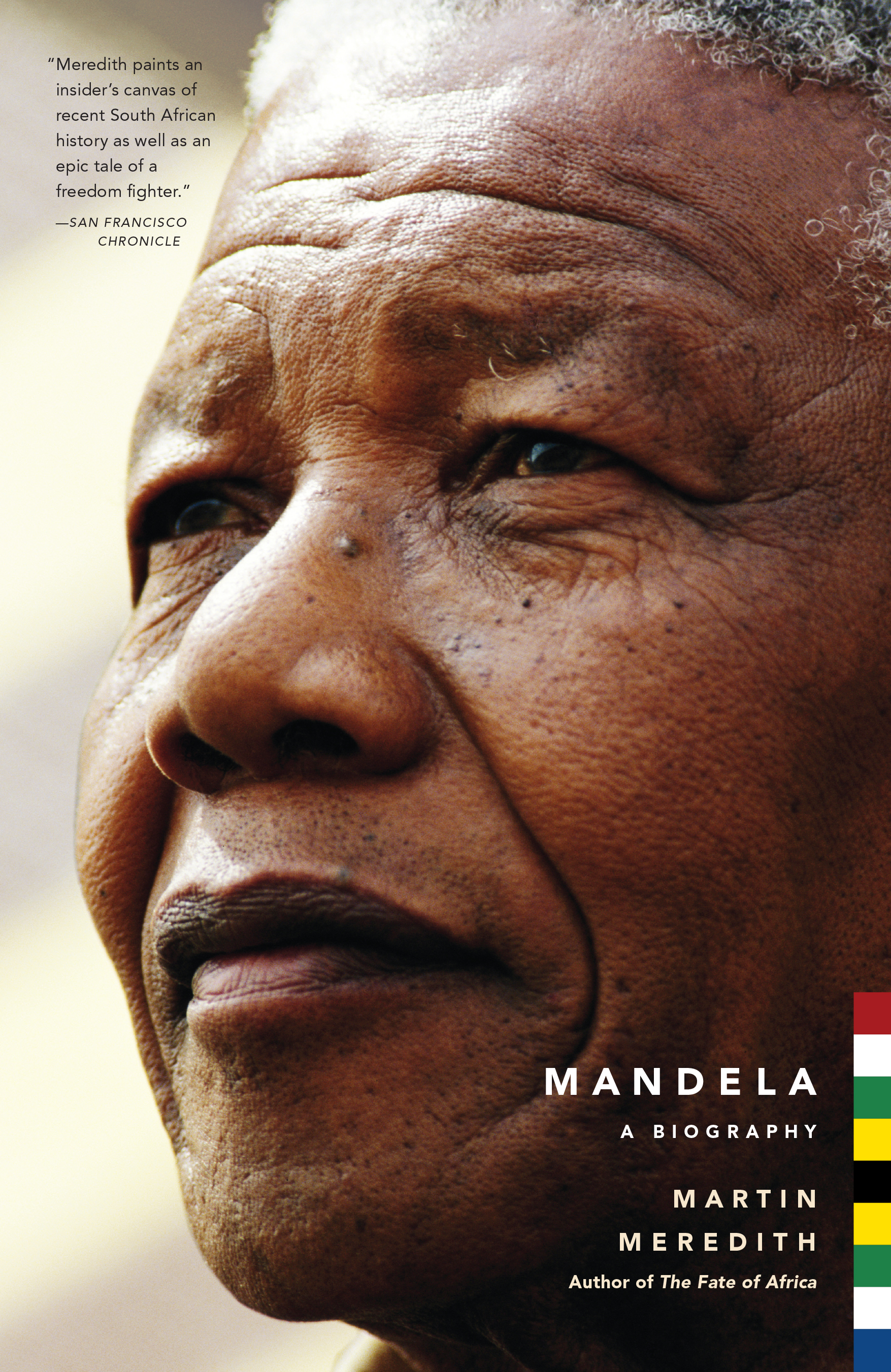

Mandela

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 30, 2010

- Page Count

- 688 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586488666

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $29.99 $38.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 30, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Martin Meredith’s vivid portrayal of this towering leader was originally acclaimed as “an exemplary work of biography: instructive, illuminating, as well as felicitously written” (Kirkus Reviews), providing “new insights on the man and his time” (Washington Post). Now Meredith has revisited and significantly updated his biography to incorporate a decade of additional perspective and hindsight on the man and his legacy and to examine how far his hopes for the new South Africa have been realized.

Published as South Africa celebrates 100 years since its founding and hosts the 2010 World Cup, Nelson Mandela is the most thorough and up-to-date account available of the life of its most revered hero.