Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

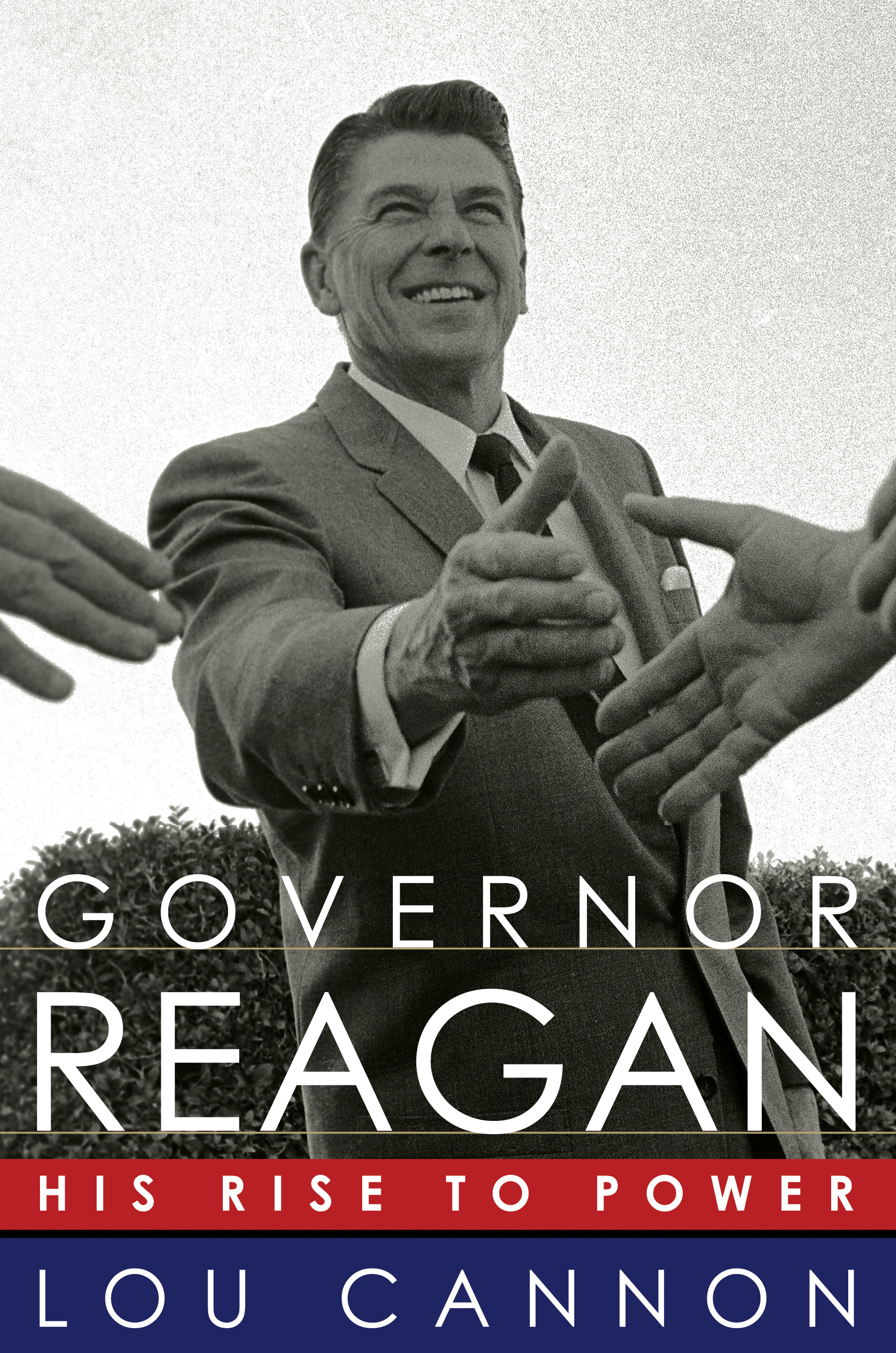

Governor Reagan

His Rise To Power

Contributors

By Lou Cannon

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2009

- Page Count

- 592 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786739219

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

At first, Reagan suffered from political amateurism, an inexperienced staff, and ideological blind spots. But he quickly learned to take the measure of the Democrats who controlled the State Legislature and surprised friends and foes alike by agreeing to a huge tax increase, which made it possible for him to govern for eight years without additional tax hikes. He developed an environmental policy that preserved the state ‘s scenic valleys and wild rivers, and he signed into law what was then the nation’s most progressive declaration on abortion rights. His quixotic 1968 presidential campaign revealed his higher ambitions to the world and taught him how much he had to learn about big-league politics.

Written by the definitive biographer of Ronald Reagan, this new biography is a classic study of a fascinating individual’s evolution from a conservative hero to a national figure whose call for renewal stirred Republicans, working-class Democrats, and independents alike.