Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

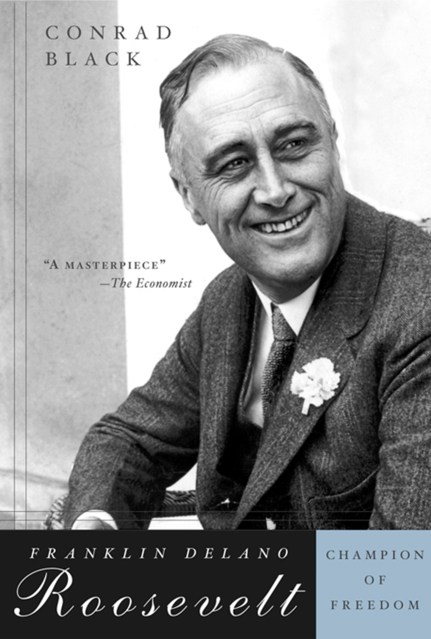

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Champion of Freedom

Contributors

By Conrad Black

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2012

- Page Count

- 1328 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392136

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $14.99 $19.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Conrad Black rises to the challenge. In this magisterial biography, Black makes the case that FDR was the most important person of the twentieth century, transforming his nation and the world through his unparalleled skill as a domestic politician, war leader, strategist, and global visionary — all of which he accomplished despite a physical infirmity that could easily have ended his public life at age thirty-nine. Black also takes on the great critics of FDR, especially those who accuse him of betraying the West at Yalta. Black opens a new chapter in our understanding of this great man, whose example is even more inspiring as a new generation embarks on its own rendezvous with destiny.