By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

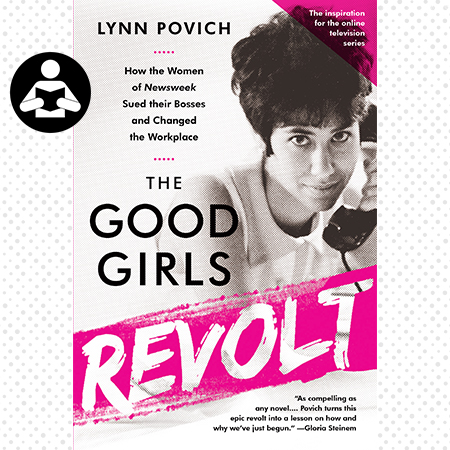

The Good Girls Revolt

How the Women of Newsweek Sued their Bosses and Changed the Workplace

Contributors

By Lynn Povich

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2012

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391740

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Media Tie-In) $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Lynn Povich was one of the lucky ones, landing a job at Newsweek, renowned for its cutting-edge coverage of civil rights and the “Swinging Sixties.” Nora Ephron, Jane Bryant Quinn, Ellen Goodman, and Susan Brownmiller all started there as well. It was a top-notch job — for a girl — at an exciting place.

But it was a dead end. Women researchers sometimes became reporters, rarely writers, and never editors. Any aspiring female journalist was told, “If you want to be a writer, go somewhere else.”

On March 16, 1970, the day Newsweek published a cover story on the fledgling feminist movement entitled “Women in Revolt,” forty-six Newsweek women charged the magazine with discrimination in hiring and promotion. It was the first female class action lawsuit–the first by women journalists — and it inspired other women in the media to quickly follow suit.

Lynn Povich was one of the ringleaders. In The Good Girls Revolt, she evocatively tells the story of this dramatic turning point through the lives of several participants. With warmth, humor, and perspective, she shows how personal experiences and cultural shifts led a group of well-mannered, largely apolitical women, raised in the 1940s and 1950s, to challenge their bosses — and what happened after they did. For many, filing the suit was a radicalizing act that empowered them to “find themselves” and fight back. Others lost their way amid opportunities, pressures, discouragements, and hostilities they weren’t prepared to navigate.

The Good Girls Revolt also explores why changes in the law didn’t solve everything. Through the lives of young female journalists at Newsweek today, Lynn Povich shows what has — and hasn’t — changed in the workplace.

-

"The Good Girls Revolt is as compelling as any novel, and also an accurate, intimate history of new women journalists invading the male journalistic world of the 1970s. Lynn Povich turns this epic revolt into a lesson on why and how we've just begun."GloriaSteinem

-

"A meticulously reported and highly readable account of a pivotal time in the women's movement."Jeannette Walls

-

"Povich's in-depth research, narrative skills and eyewitness observations provide an entertaining and edifying look at a pivotal event in women's history."Kirkus

-

"The personal and the political are deftly interwoven in the fast-moving narrative.... The Good Girls Revolt has many timely lessons for working women who are concerned about discrimination today....But this sparkling, informative book may help move these goals a tiny bit closer."NewYork Times

-

"Solidly researched and should interest readers who care about feminist history and how gender issues play out in the culture."Boston Globe

-

"Povich's memoir of the tortuous, landmark battle that paved the way for a generation of female writers and editors is illuminating in its details [and] casts valuable perspective on a trail-blazing case that shouldn't be forgotten."Macleans

-

"[Povich] strikes a fair tone, neither naïve nor sanctimonious.... Among her achievements is a complex portrait of Newsweek Editor Osborn Elliott and his path from defensive adversary to understanding ally."AmericanJournalism Review

-

"Women still have a long way to go, the journalist Lynn Povich rousingly reminds readers in The Good Girls Revolt, her fascinating (and long overdue) history of the class-action lawsuit undertaken by four dozen female researchers and underlings at Newsweek magazine four decades ago.... If ever a book could remind women to keep their white gloves off and to keep fighting the good fight, this is the one."LieslSchillinger, New York Times

-

"Crisp, revealing.... [A] taut, firsthand account of how a group of razor-sharp, courageous women successfully fought back against institutional sexism at one of the country's most esteemed publications."Washingtonian

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use