Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

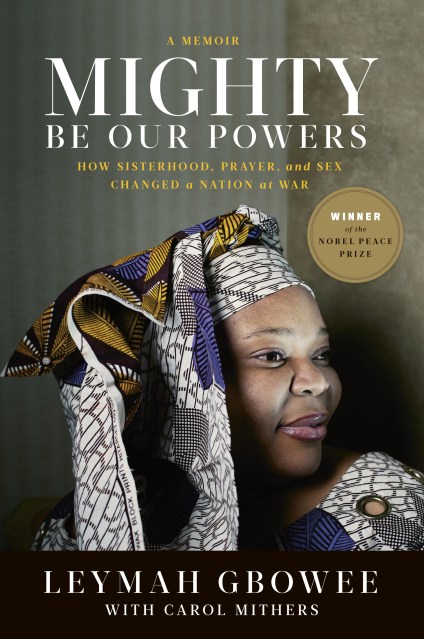

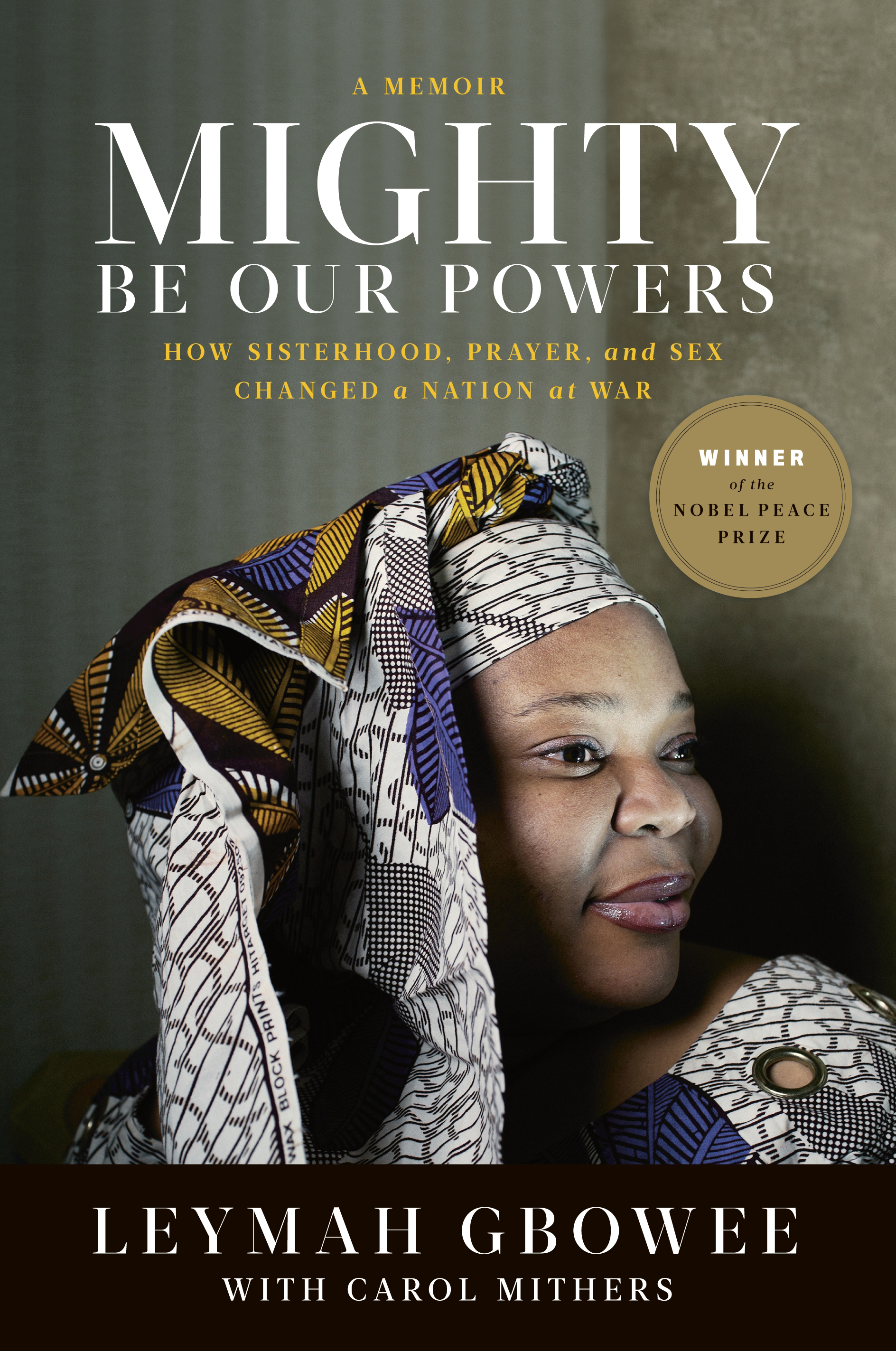

Mighty Be Our Powers

How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War

Contributors

With Carol Mithers

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2011

- Page Count

- 260 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780984295142

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As a young woman, Leymah Gbowee was broken by the Liberian civil war, a brutal conflict that destroyed her country and claimed the lives of countless relatives and friends. Propelled by her realization that it is women and girls who suffer most during conflicts, she found the courage to turn her bitterness into action.

She helped organize and then lead the Liberian Mass Action for Peace, which brought together Christian and Muslim women in a nonviolent movement that engaged in public protest, confronted Liberia’s ruthless president and rebel warlords, and even held a sex strike.

With an army of women, Gbowee helped lead her nation to peace-and became an international leader who changed history, won the Nobel Peace Prize for her work, and fiercely advocates for girls’ empowerment and leadership. Mighty Be Our Powers is the gripping chronicle of a journey from hopelessness to liberation that will touch all who dream of a better world.