Promotion

25% off sitewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery! Code BEST25 automatically applied at checkout!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

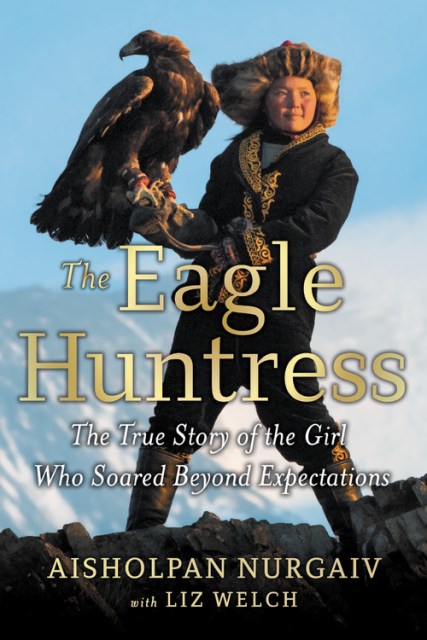

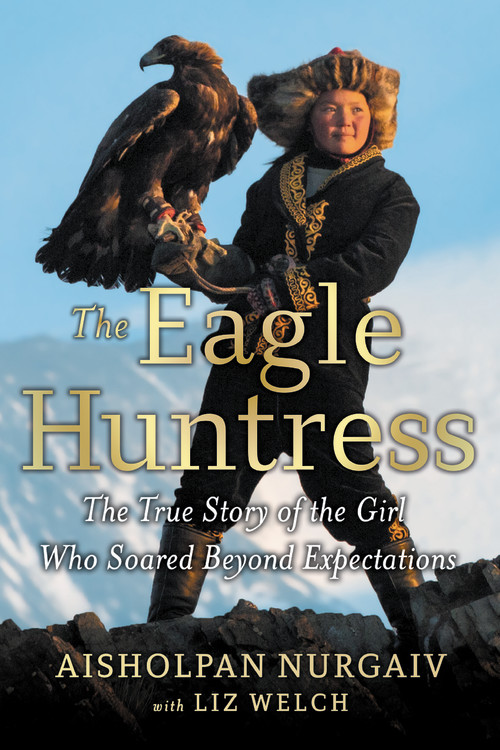

The Eagle Huntress

The True Story of the Girl Who Soared Beyond Expectations

Contributors

With Liz Welch

By Aisholpan Nurgaiv

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 12, 2020

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316522618

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 12, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this compelling memoir, teenaged eagle hunter Aisholpan Nurgaiv tells her own story for the first time, speaking directly with award-winning and New York Times bestselling author Liz Welch (I Will Always Write Back), who traveled to Mongolia for this book. Nurgaiv’s story and fresh, sincere voice are not only inspiring but truly magnificent: with the support of her father, she captured and trained her own golden eagle and won the Ölgii eagle festival. She was the only girl to compete in the festival.

Filled with stunning photographs, The Eagle Huntress is a striking tale of determination– of a girl who defied expectations and achieved what others declared impossible. Aisholpan Nurgaiv’s story is both unique and universally relatable: a memoir of survival, empowerment, and the positive impact of one person’s triumph.

-

"[A] glimpse into another culture.... Recommended."School Library Journal

-

"Nurgaiv's love for and pride in her homeland, culture, and family come through with quiet, persuasive power. An intriguing memoir from a girl who's become a cultural icon."Kirkus

-

"Young readers will be intrigued by the details of eagle hunting and the nomadic lifestyle.... An accessibly written, steadily paced story of perseverance and self-confidence."School Library Connection

-

"A great stand-alone or companion to the documentary film The Eagle Huntress."Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use