By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

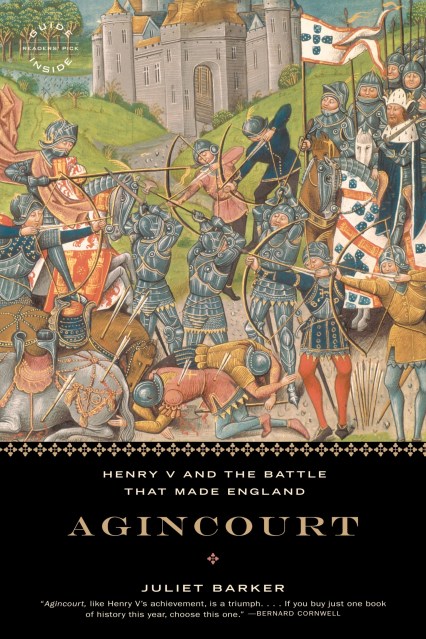

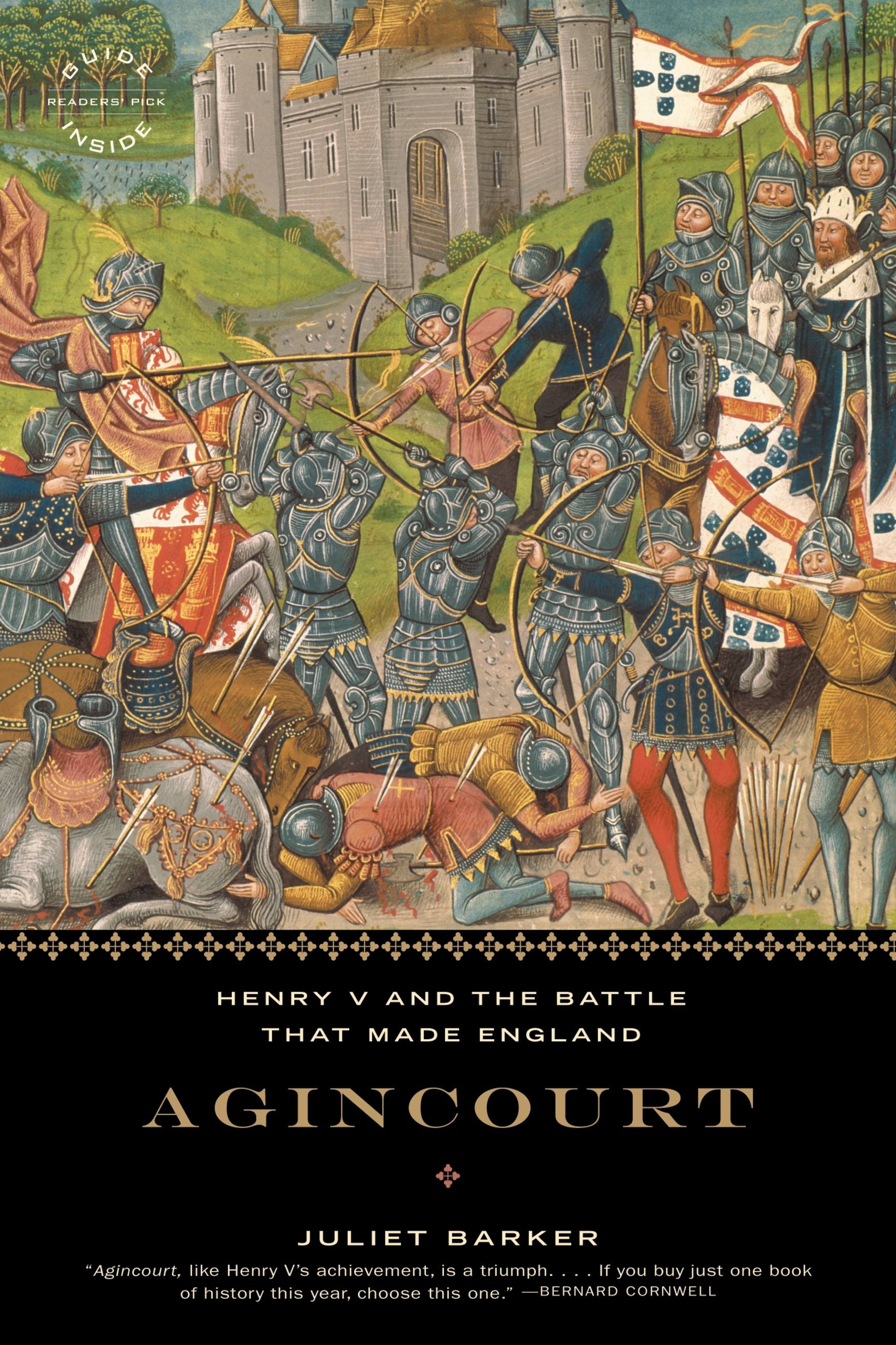

Agincourt

Henry V and the Battle That Made England

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 23, 2007

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316015042

Price

$24.99Format

Format:

Trade Paperback $24.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 23, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a master historian comes an astonishing chronicle of life in medieval Europe and the battle that altered the course of an empire.

Although almost six centuries old, the Battle of Agincourt still captivates the imaginations of men and women on both sides of the Atlantic.

It has been immortalized in high culture (Shakespeare’s Henry V) and low (the New York Post prints Henry’s battle cry on its editorial page each Memorial Day). It is the classic underdog story in the history of warfare, and generations have wondered how the English — outnumbered by the French six to one — could have succeeded so bravely and brilliantly.

Drawing upon a wide range of sources, eminent scholar Juliet Barker casts aside the legend and shows us that the truth behind Agincourt is just as exciting, just as fascinating, and far more significant. She paints a gripping narrative of the October 1415 clash between outnumbered English archers and heavily armored French knights. But she also takes us beyond the battlefield into palaces and common cottages to bring into vivid focus an entire medieval world in flux. Populated with chivalrous heroes, dastardly spies, and a ferocious and bold king, Agincourt is as earthshaking as its subject — and confirms Juliet Barker’s status as both a historian and a storyteller of the first rank.

Although almost six centuries old, the Battle of Agincourt still captivates the imaginations of men and women on both sides of the Atlantic.

It has been immortalized in high culture (Shakespeare’s Henry V) and low (the New York Post prints Henry’s battle cry on its editorial page each Memorial Day). It is the classic underdog story in the history of warfare, and generations have wondered how the English — outnumbered by the French six to one — could have succeeded so bravely and brilliantly.

Drawing upon a wide range of sources, eminent scholar Juliet Barker casts aside the legend and shows us that the truth behind Agincourt is just as exciting, just as fascinating, and far more significant. She paints a gripping narrative of the October 1415 clash between outnumbered English archers and heavily armored French knights. But she also takes us beyond the battlefield into palaces and common cottages to bring into vivid focus an entire medieval world in flux. Populated with chivalrous heroes, dastardly spies, and a ferocious and bold king, Agincourt is as earthshaking as its subject — and confirms Juliet Barker’s status as both a historian and a storyteller of the first rank.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use