By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

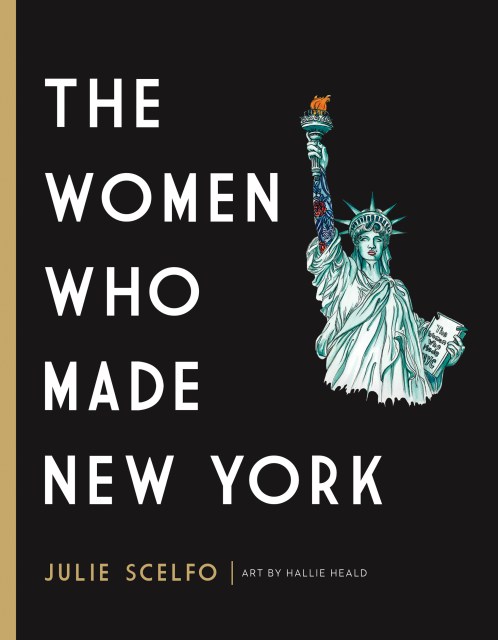

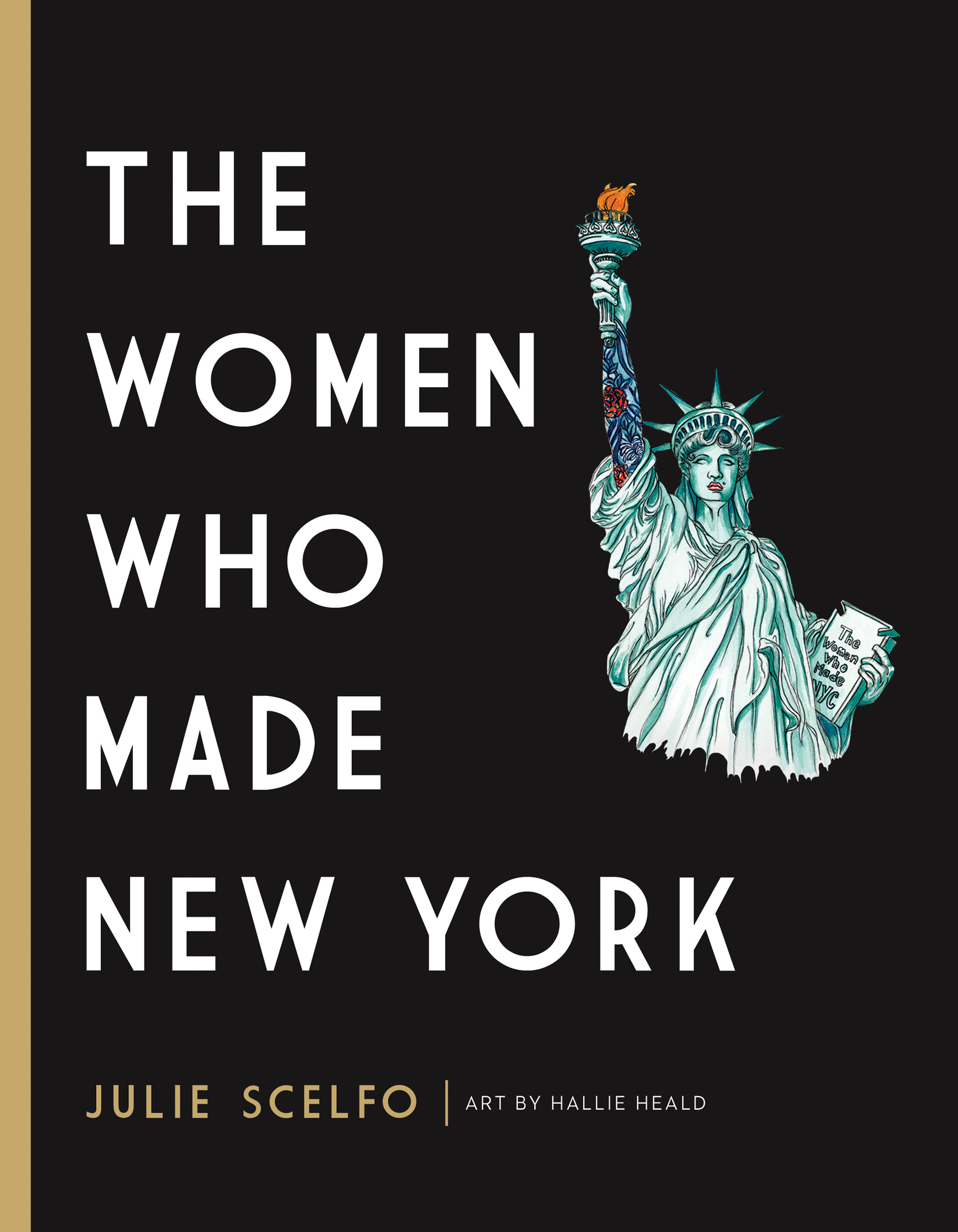

The Women Who Made New York

Contributors

By Julie Scelfo

Illustrated by Hallie Heald

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 15, 2016

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056540

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 15, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Read any history of New York City and you will read about men. You will read about men who were political leaders and men who were activists and cultural tastemakers. These men have been lauded for generations for creating the most exciting and influential city in the world.

But that’s not the whole story.

The Women Who Made New York reveals the untold stories of the phenomenal women who made New York City the cultural epicenter of the world. Many were revolutionaries and activists, like Zora Neale Hurston and Audre Lorde. Others were icons and iconoclasts, like Fran Lebowitz and Grace Jones. There were also women who led quieter private lives but were just as influential, such as Emily Warren Roebling, who completed the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge when her engineer husband became too ill to work.

Paired with striking, contemporary illustrations by artist Hallie Heald, The Women Who Made New York offers a visual sensation — one that reinvigorates not just New York City’s history but its very identity.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use