By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

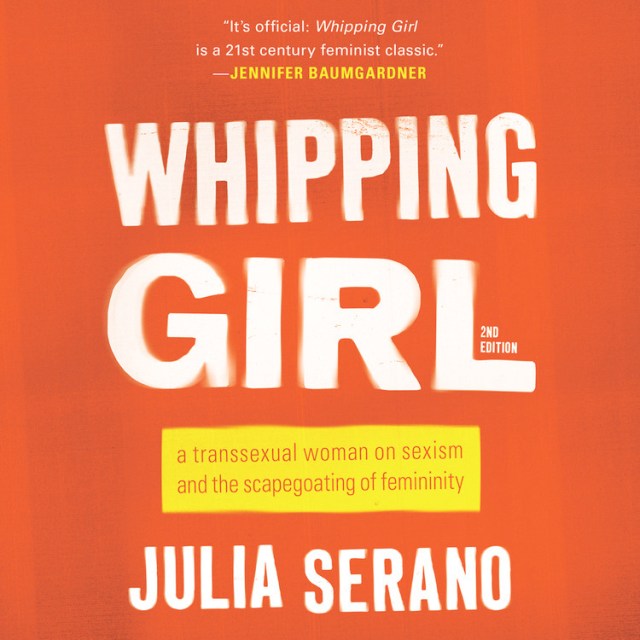

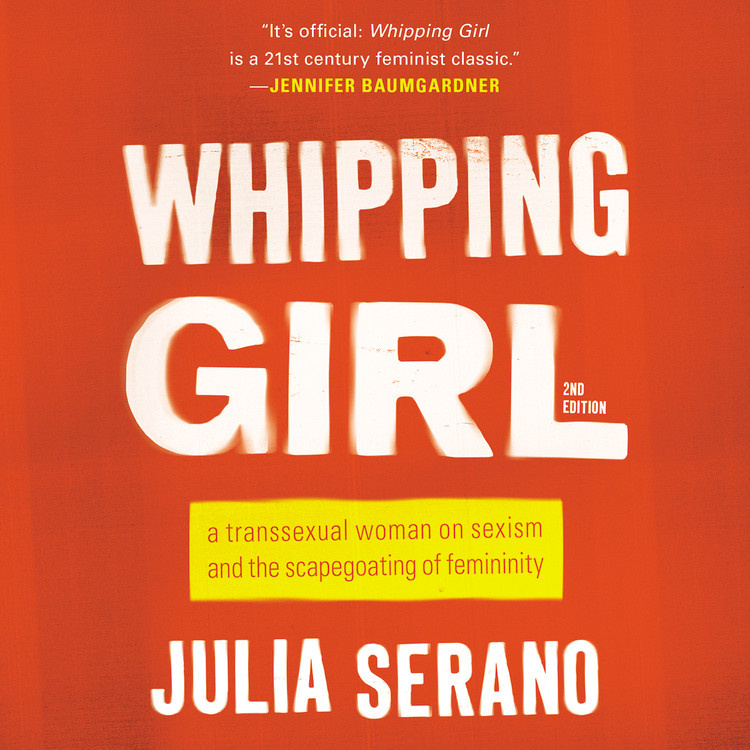

Whipping Girl

A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity

Contributors

By Julia Serano

Read by Julia Serano

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 25, 2016

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478971719

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 25, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A foundational text for anyone hoping to understand transgender politics and culture in the U.S. today.” —NPR

Named as one of 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of All Time by Ms. Magazine

Julia Serano shares her experiences and insights—both pre- and post-transition—to reveal the ways in which fear, suspicion, and dismissiveness toward femininity shape our societal attitudes toward trans women, as well as gender and sexuality as a whole.

Serano's well-honed arguments and pioneering advocacy stem from her ability to bridge the gap between the often-disparate biological and social perspectives on gender. In this provocative manifesto, she exposes how deep-rooted the cultural belief is that femininity is frivolous, weak, and passive.

In addition to debunking popular misconceptions about being transgender, Serano makes the case that today's feminists and transgender activists must work to embrace and empower femininity—in all of its wondrous forms.

Named as one of 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of All Time by Ms. Magazine

Julia Serano shares her experiences and insights—both pre- and post-transition—to reveal the ways in which fear, suspicion, and dismissiveness toward femininity shape our societal attitudes toward trans women, as well as gender and sexuality as a whole.

Serano's well-honed arguments and pioneering advocacy stem from her ability to bridge the gap between the often-disparate biological and social perspectives on gender. In this provocative manifesto, she exposes how deep-rooted the cultural belief is that femininity is frivolous, weak, and passive.

In addition to debunking popular misconceptions about being transgender, Serano makes the case that today's feminists and transgender activists must work to embrace and empower femininity—in all of its wondrous forms.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use